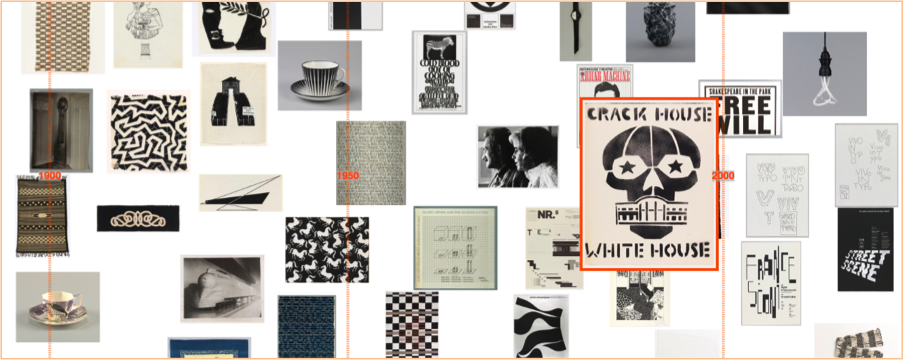

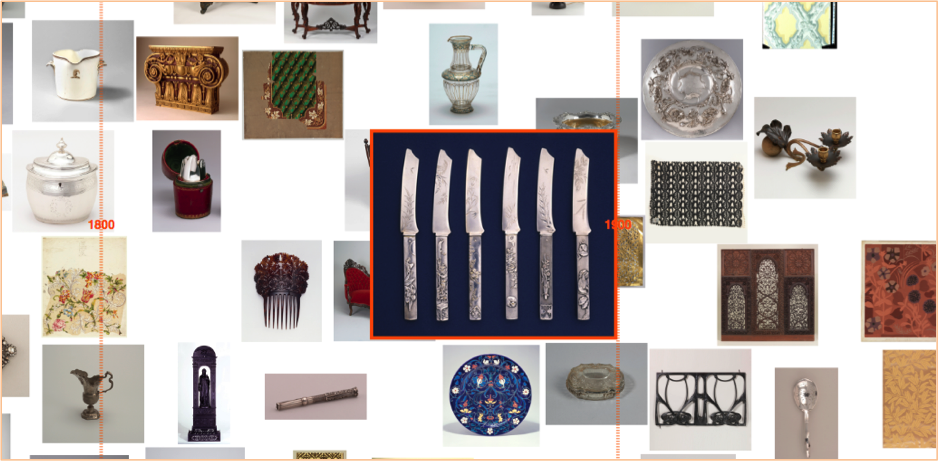

‘Black & white’ timeline detail, Cooper Hewitt data

‘Black & white’ timeline detail, Cooper Hewitt data

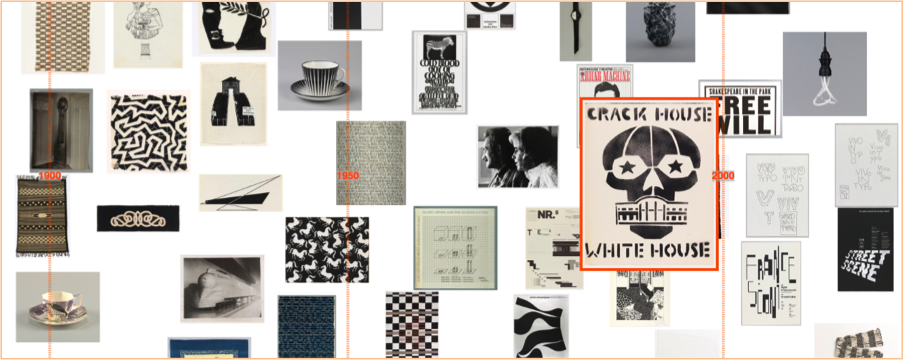

“A physical museum is itself a sort of data set — an aggregation of the micro in order to glimpse the macro. One vase means little on its own, beyond perhaps illustrating a scene from daily life. But together with its contemporaries, it means the contours of a civilization. And when juxtaposed against all vases, it helps create a first-hand account of the history of the world.”

From ‘An Excavation Of One Of The World’s Greatest Art Collections’

“The ability to draw on historic examples from various cultures, to access forgotten techniques and ideas and juxtapose them with contemporary works, creates provocative dialogues and amplifies the historic continuum. This range is an asset few museums have or utilize and provides a continuing source of inspiration to contemporary viewers and designers.”

From ‘Making Design: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Collection’ p.28

Guest post by Olivia Vane

I’m 4 months into a 5-month fellowship at Cooper Hewitt working with their digitised collection. I’m normally based in London where I’m a PhD student in Innovation Design Engineering at the Royal College of Art supervised by Stephen Boyd Davis, Professor of Design Research. My PhD topic is designing and building interactive timelines for exploring cultural data (digitised museum, archive and library collections). And, in London, I have been working with partners at the V&A, the Wellcome Library and the Science Museum.

The key issue in my PhD is how we ‘make sense’ of history using interactive diagrams. This is partly about visualisation of things we already know in order to communicate them to others. But it is also about visual analytics – using visuals for knowledge discovery. I’m particularly interested in what connects objects to one another, across time and through time.

I am very fortunate to be spending time at Cooper Hewitt as they have digitised their entire collection, more than 200,000 objects, and it is publicly available through an API. The museum is also known for its pioneering work in digital engagement with visitors and technical innovations in the galleries. It is a privilege to be able to draw on the curatorial, historical and digital expertise of the staff around me here for developing and evaluating my designs.

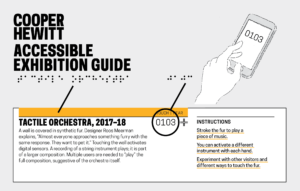

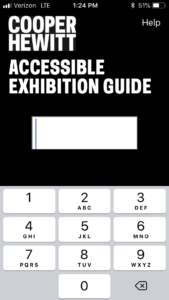

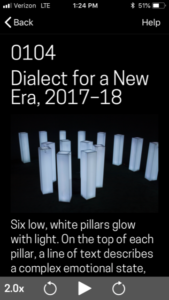

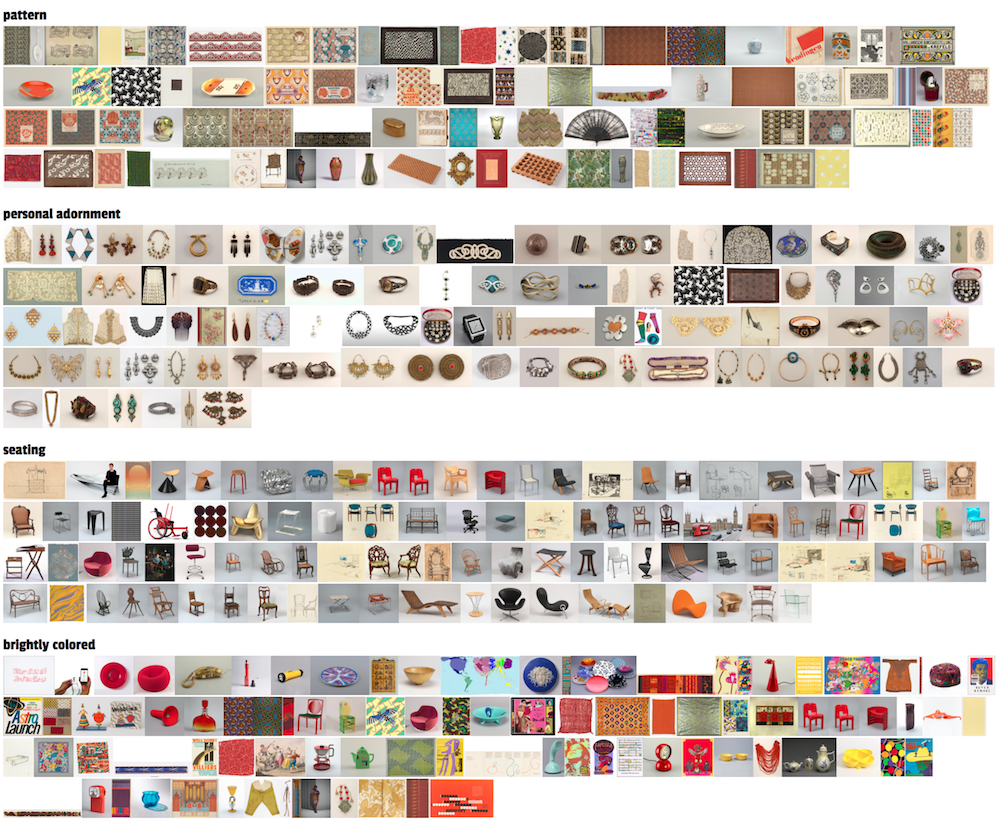

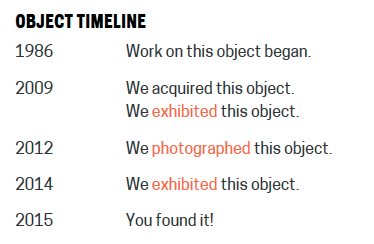

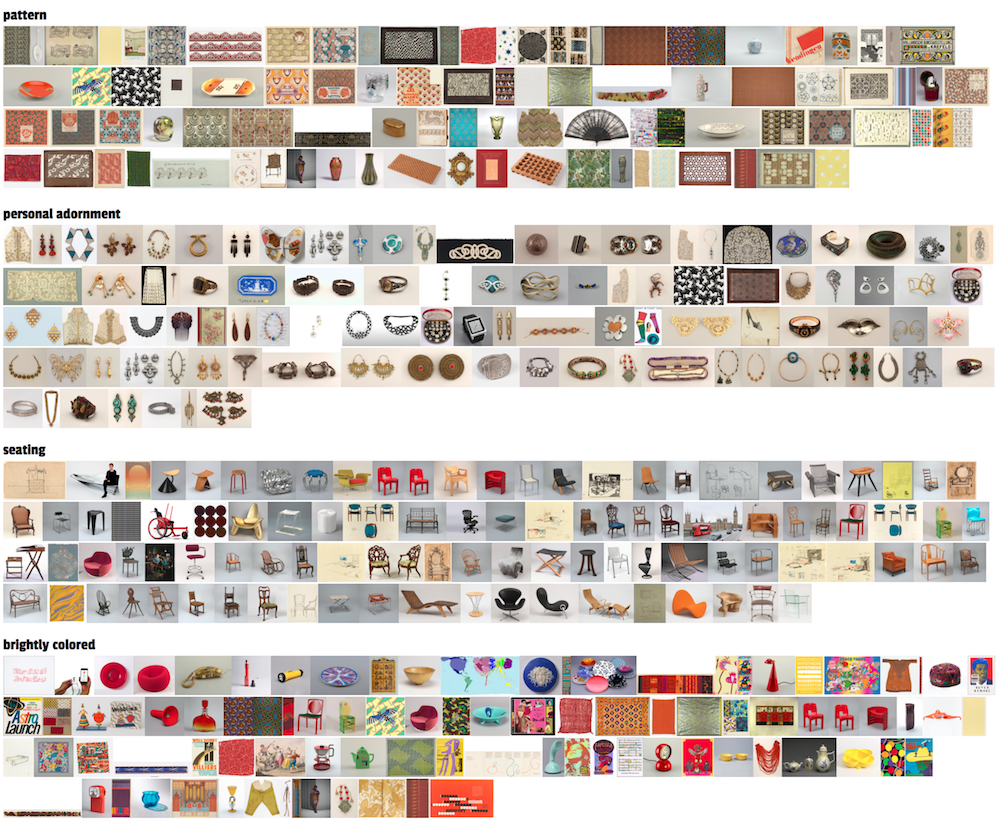

As I began exploring the collection API, I noticed many of the object records had ‘tags’ applied to them (like ‘birds’, ‘black & white’, ‘coffee and tea drinking’, ‘architecture’, ‘symmetry’ or ‘overlapping’). These tags connect diverse objects from across the collection: they represent themes that extend over time and across the different museum departments. This tagging interested me because it seemed to offer different paths through the data around shape, form, style, texture, motif, colour, function or environment. (It’s similar to the way users on platforms like Pinterest group images into ‘boards’ around different ideas). An object can have many tags applied to it suggesting different ways to look at it, and different contexts to place it in.

Where do these tags come from? Here, the tags are chosen and applied by the museum when objects are included in an exhibition. They provide a variety of ways to think about an object, highlighting different characteristics, and purposely offer a contrasting approach to more scholarly descriptive information. The tags are used to power recommendation systems on the museum collection website and applications in the galleries. They constitute both personal and institutional interpretation of the collection, and situate each item in a multi-dimensional set of context.

Some examples of tags and tagged objects in the Cooper Hewitt collection

I was interested to trace these themes over the collection and, since objects often have multiple tags, to explore what it would be like to situate or view each object through these various lenses.

The temporal dimension is important for identifying meaningful connections between items in cultural collections, so my first thoughts were to map tagged objects by date.

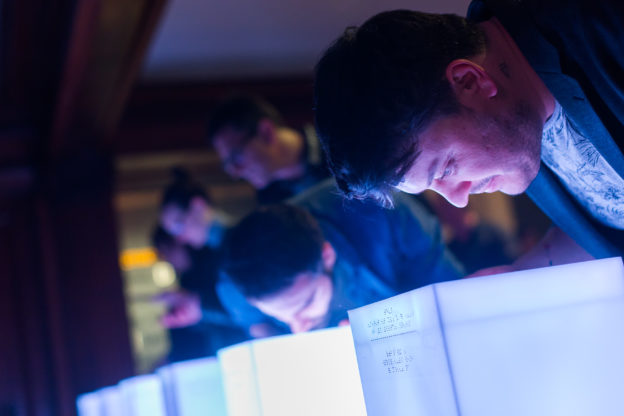

I’m working on a prototype interface that allows users to browse in a visually rich way through the collection by tags. A user starts with one object image and a list of the tags that apply to that object. They may be interested to see what other objects in the collection share a given tag and how the starting image sits in each of those contexts. When they click a tag, a timeline visualisation is generated of images of the other objects sharing that tag – arranged by date. The user can then click on further tags, to generate new timeline visualisations around the same starting image, viewing that image against contrasting historical narratives. And if they see a different image that interests them in one of these timelines, they can click on that image making it the new central image with a new list of tags through which to generate timelines and further dig into the collection. By skipping from image to image and tag to tag, it’s easy to get absorbed in exploring the dataset this way; the browsing can be undirected and doesn’t require a familiarity with the dataset.

‘Coffee and tea drinking’ timeline: designs in the collection stretch from 1700 to the present with a great diversity of forms and styles, elaborate and minimal.

‘Water’ timeline. Here there are many different ways of thinking about water: images of garden plans with fountains and lakes from the 16th–18th Century, or modern interventions for accessing and cleaning water in developing countries. Contrasting representations (landscape painting to abstracted pattern) and functions (drinking to boating) stretch between.

‘Water’ timeline. Here there are many different ways of thinking about water: images of garden plans with fountains and lakes from the 16th–18th Century, or modern interventions for accessing and cleaning water in developing countries. Contrasting representations (landscape painting to abstracted pattern) and functions (drinking to boating) stretch between.

‘Water’ timeline, detail

‘Water’ timeline, detail

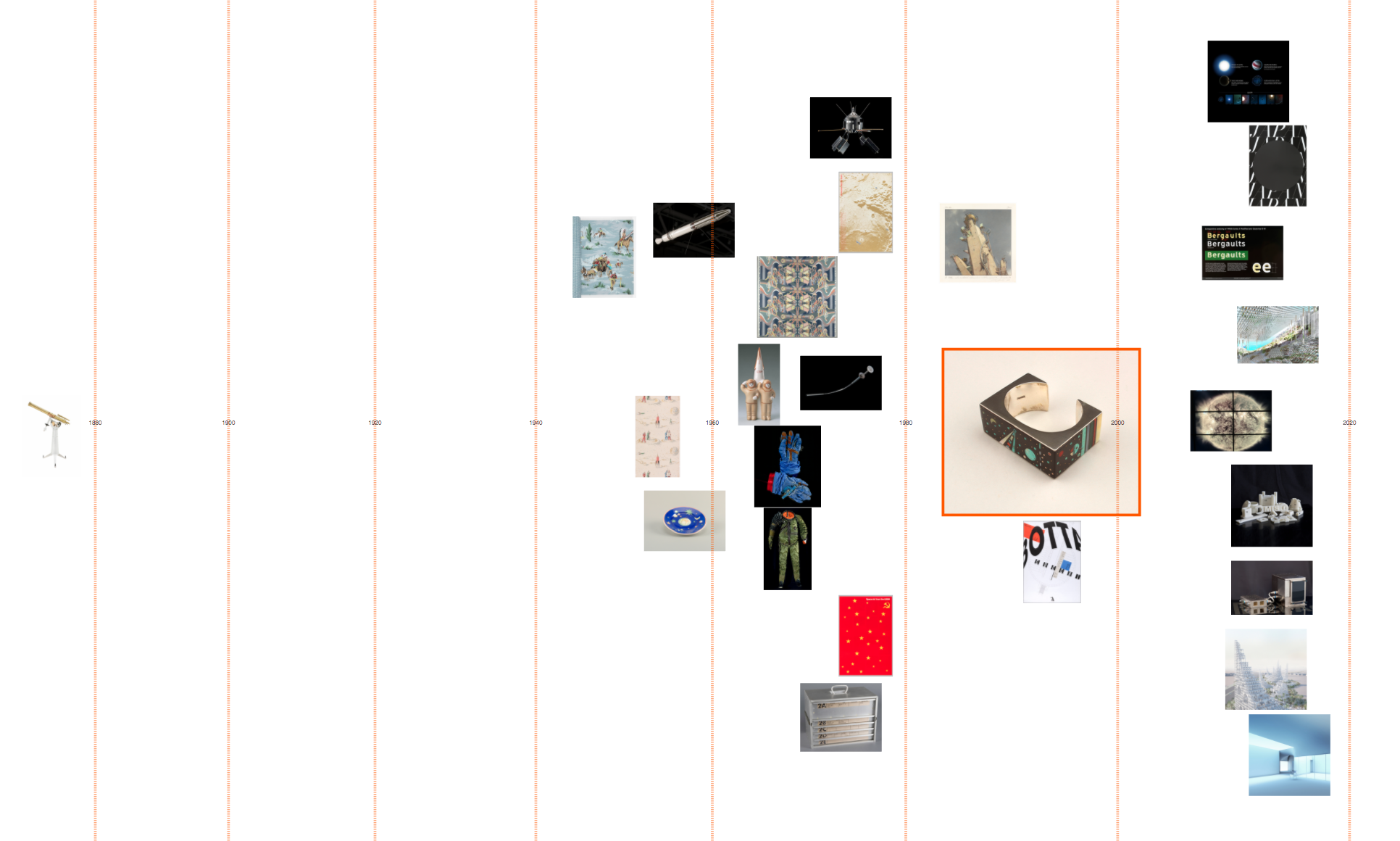

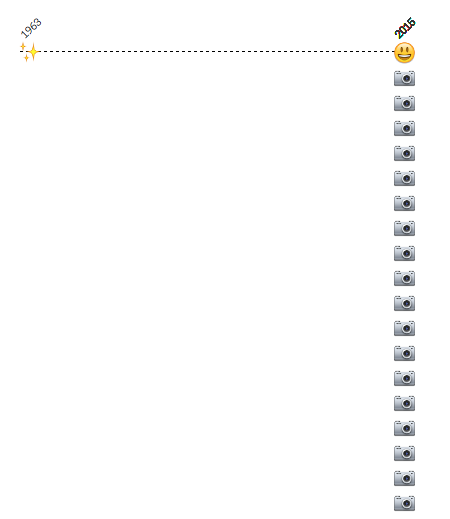

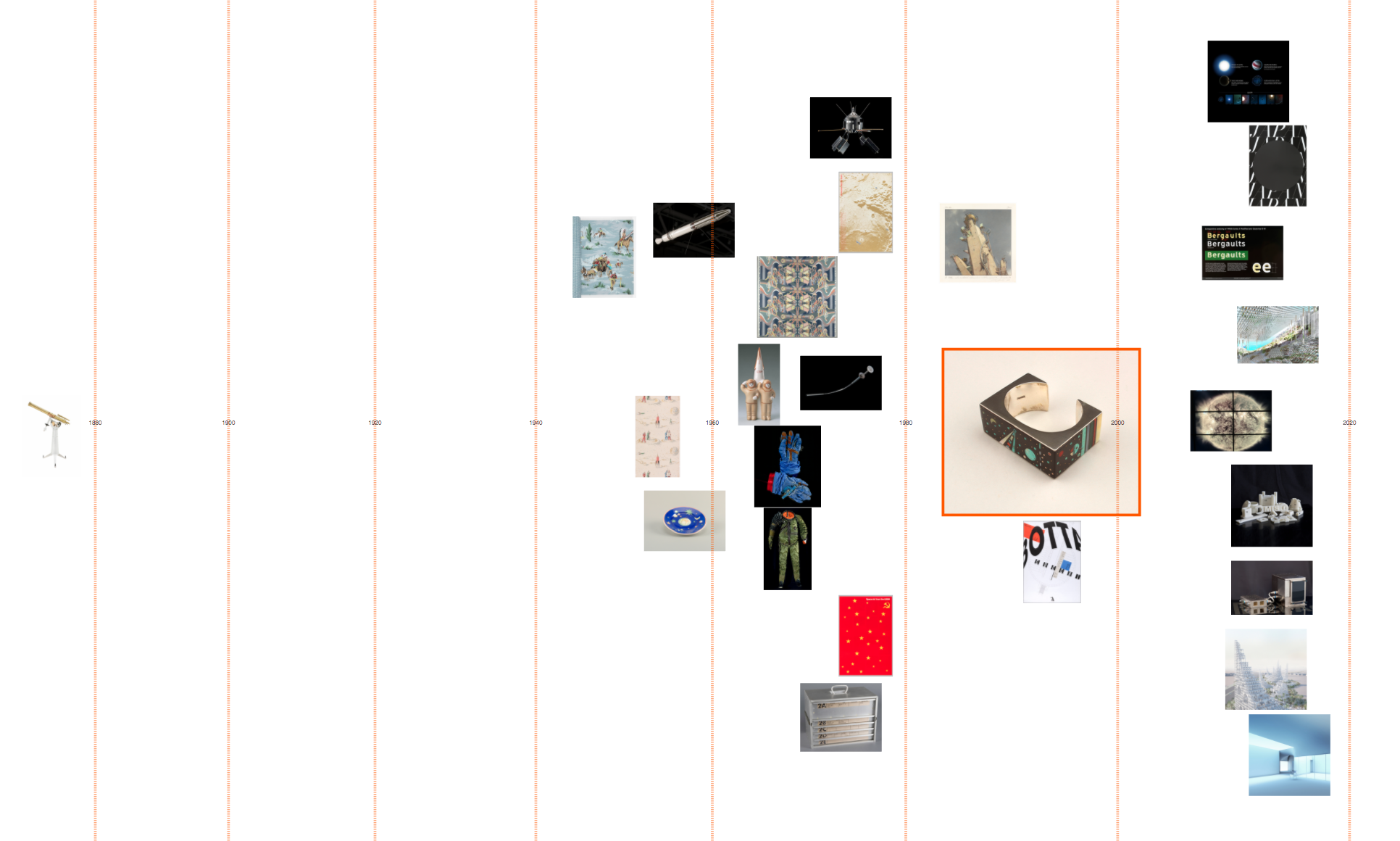

‘Space’ timeline: 1960s ‘space age’ souvenirs (Soviet and American) precede modern telescope imaging. And a 19th Century telescope reminds us of the long history of mankind’s interest in space.

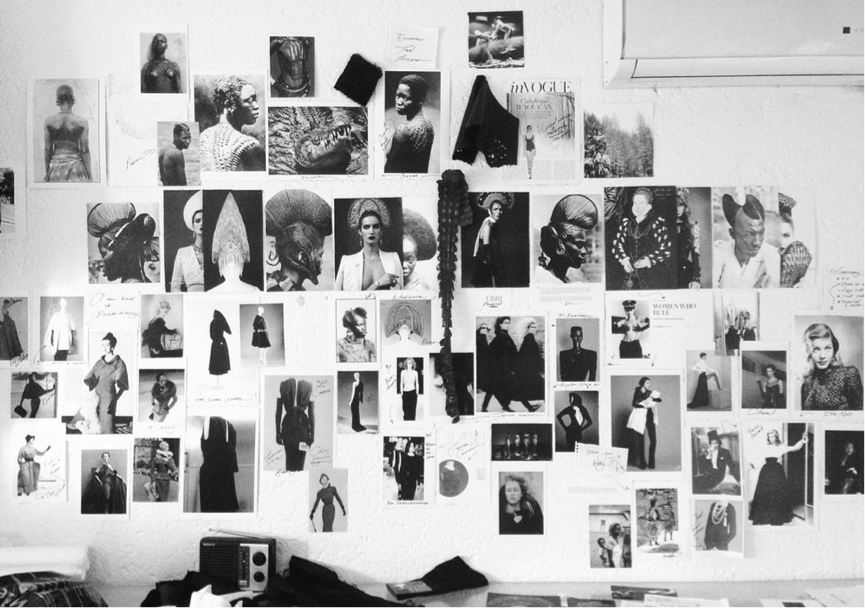

I’m plotting the object images themselves as data points so users can easily make visual connections between them and observe trends over time (for instance in how an idea is visually represented or embodied in objects, or the types of objects present at different points in time). The images are arranged without overlapping, but in an irregular way. I hoped to emulate a densely packed art gallery wall or mood board to encourage these visual connections. Since the tags are subjective and haven’t been applied across the whole collection, I also felt this layout would encourage users to view the data in a more qualitative way.

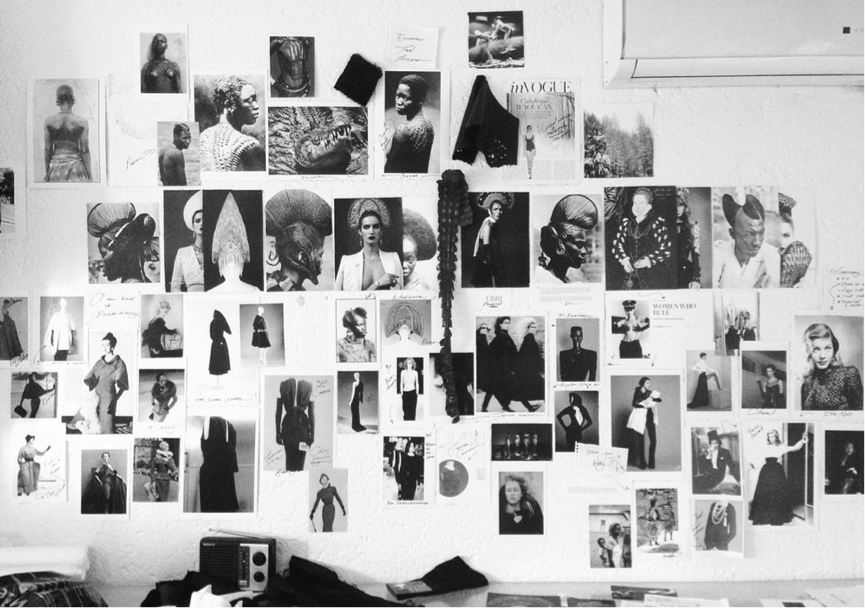

Yale Center for British Art: Long Gallery, image credit Richard Caspole, YCBA & Elizabeth Felicella, Esto

Moodboard, image credit ERRE

Moodboard, image credit ERRE

Dealing with dates

How to work with curatorial dating?

While most of the post-1800 objects in the dataset have a date/date span expressed numerically, pre-1800 objects often only have date information as it would appear on a label: for example ‘Created before 1870s’, ‘late 19th–early 20th century’, ‘ca. 1850’ or ‘2012–present’. My colleagues at the Royal College of Art have previously written about the challenges of visualising temporal data from cultural collections (Davis, S.B. and Kräutli, F., 2015. The Idea and Image of Historical Time: Interactions between Design and Digital Humanities. Visible Language, 49(3), p.101).

In order to process this data computationally, I translated the label date text to numbers using the yearrange library (which is written for working with curatorial date language). This library works by converting, for example, ‘late 18th century’ to ‘start: 1775, end: 1799’ For my purposes, this seems to work well, though I am unsure how to deal with some cases:

- How should I deal with objects whose date is ‘circa X’ or ‘ca. X’ etc.? At the moment I’m just crudely extending the date span by ±20 years.

- How should I deal with ‘before X’? How much ‘before’ does that mean? I’m currently just using X as the date in this case.

- The library does not translate BC dates (though I could make adjustments to the code to enable this…) I am just excluding these at the moment.

- There are some very old objects in the Cooper Hewitt collection for example ‘1.85 million years old’, ‘ca. 2000-1595 BCE’ and ‘300,000 years old’. These will create problems if I want to include them on a uniformly scaled timeline! Since these are rare cases, I’m excluding them at the moment.

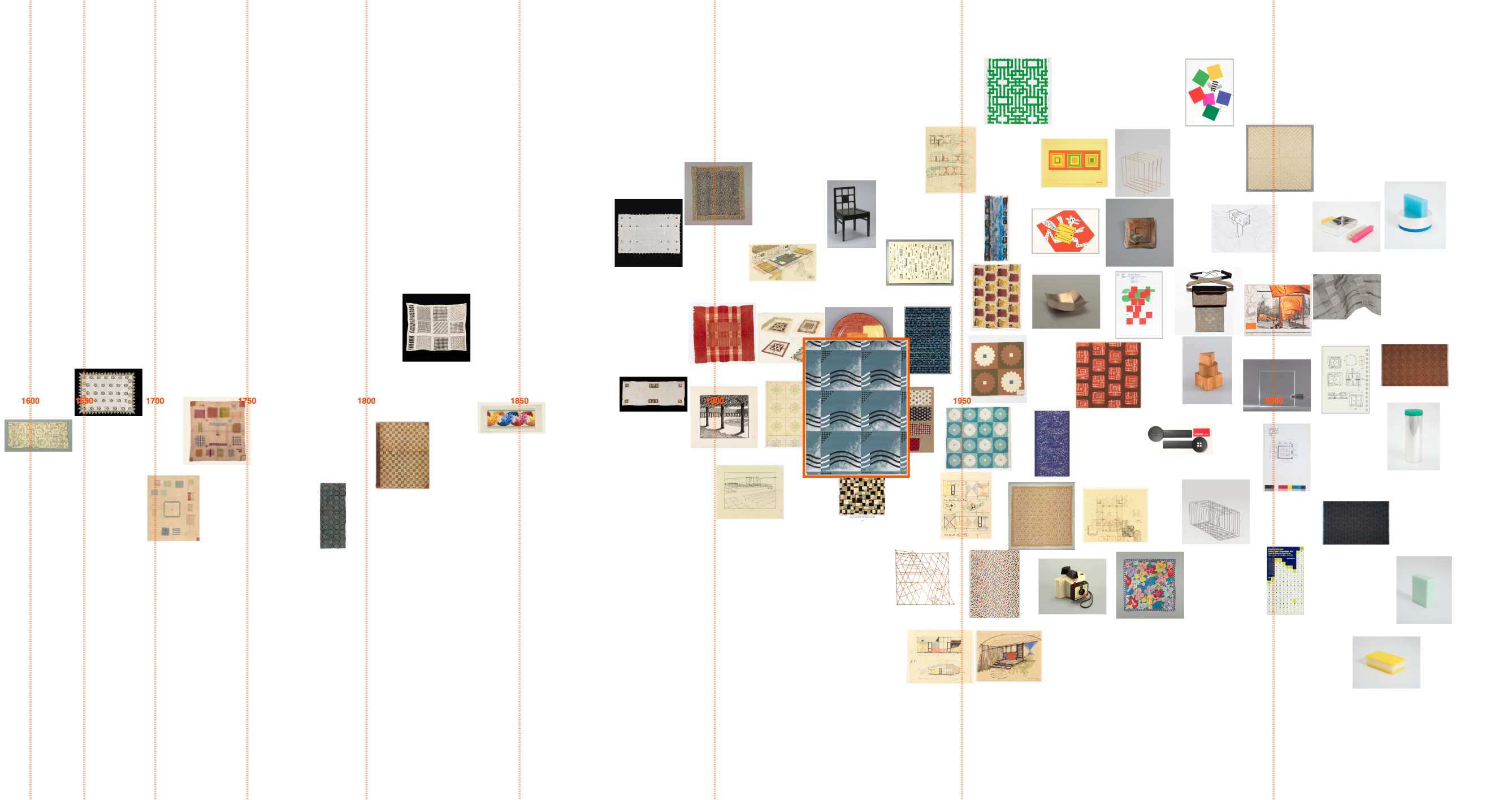

Skewing the timeline scale

The Cooper Hewitt collection is skewed towards objects dating post-1800 so to even out image distribution over the timeline I am using a power scale. Some tags, however, – such as ‘neoclassical’ or ‘art nouveau’ – have a strong temporal component and the power scale fails to even out image distribution in these cases.

How are the images arranged?

My layout algorithm aims to separate images so that they are not overlapping, but still fairly closely packed. I am using a rule that images can be shifted horizontally to avoid overlaps so long as there is still some part of the image within its date span. Since images are large data markers, it is already not possible to read dates precisely from this timeline. And the aim here is for users to observe trends and relationships, rather than read off exact dates, so I felt it was not productive to worry too much about exact placement horizontally. (Also, this is perhaps an appropriate design feature here since dating cultural objects is often imprecise and/or uncertain anyway). This way the images are quite tightly packed, but don’t stray too far from their dates.

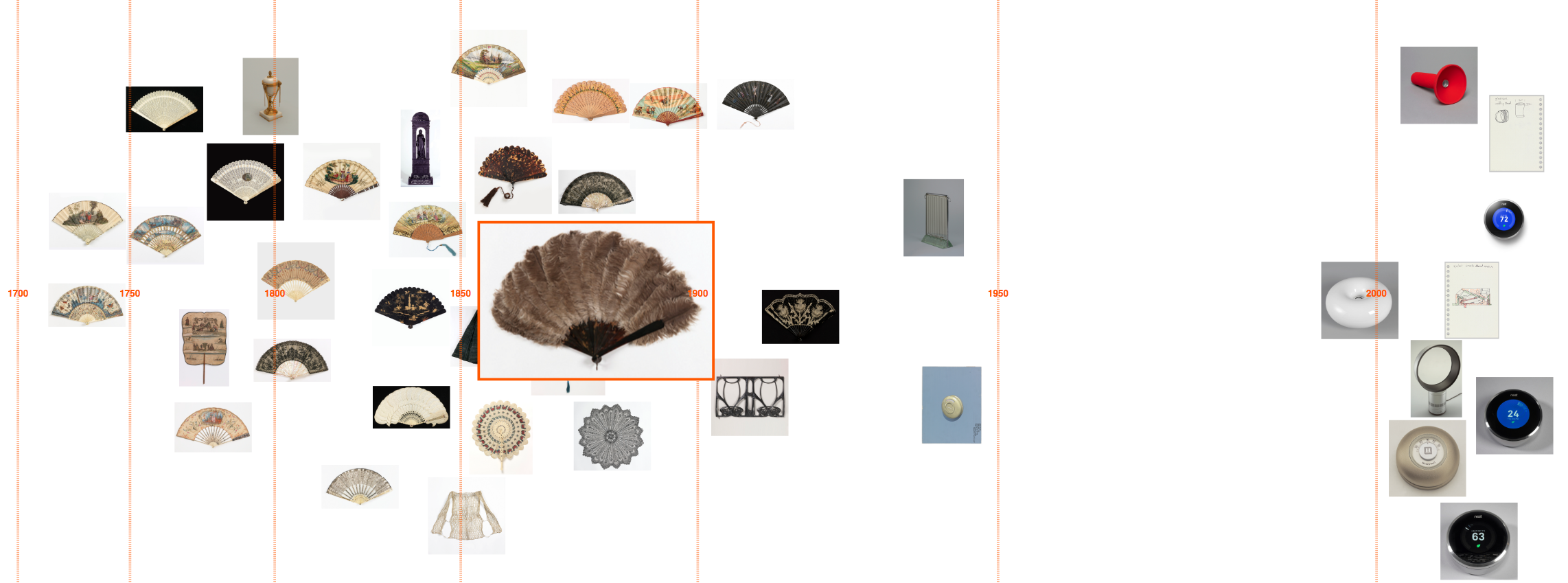

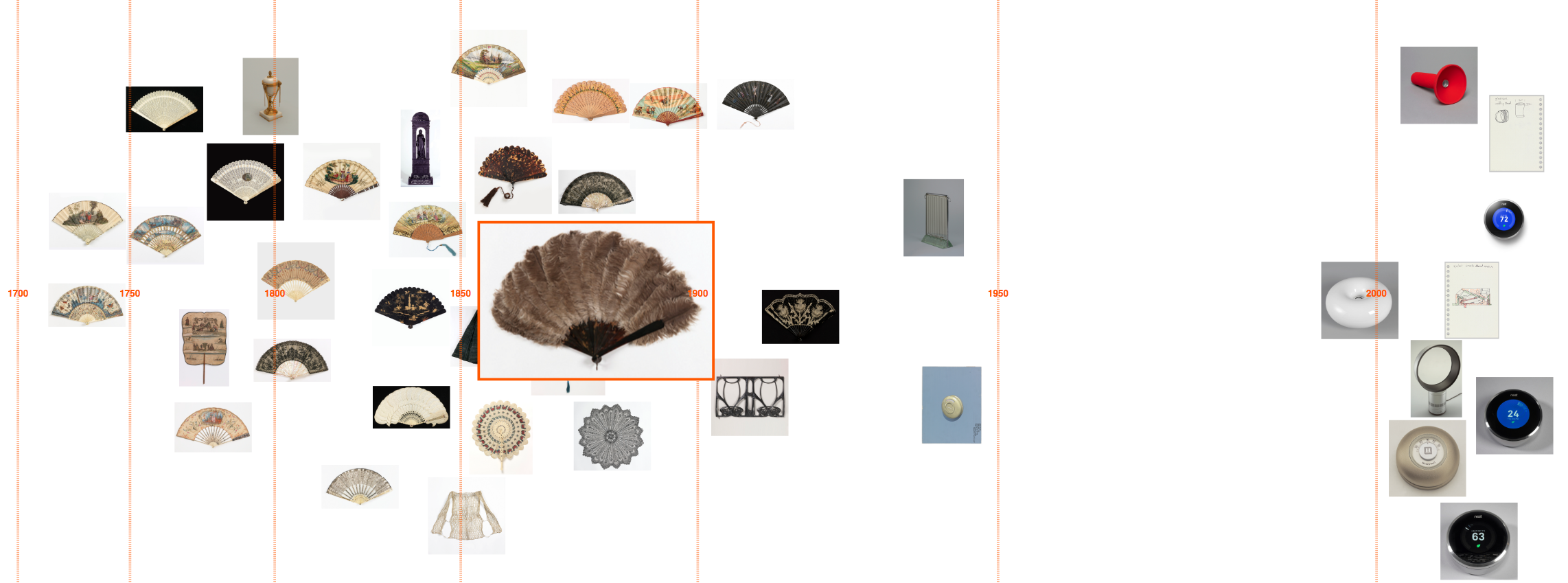

‘Personal environmental control’ timeline: a dry juxtaposition of these decorated fans against modern Nest thermostats.

‘Personal environmental control’ timeline: a dry juxtaposition of these decorated fans against modern Nest thermostats.

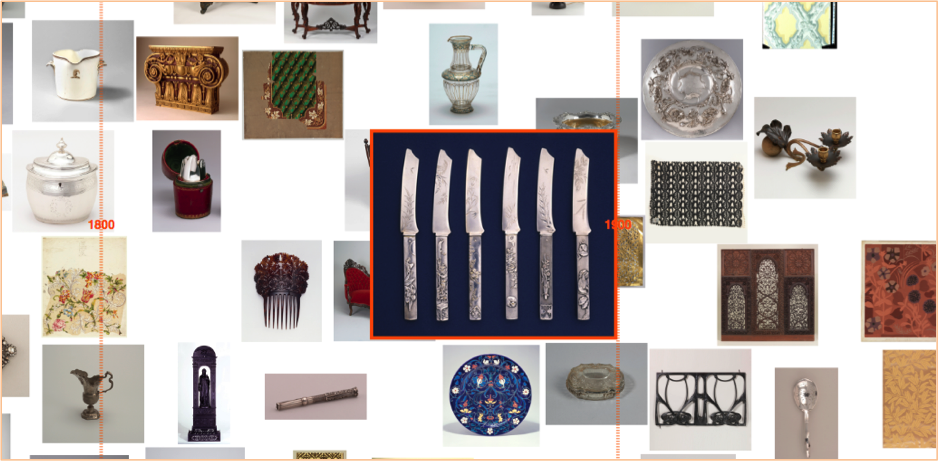

‘Foliate’ timeline, detail

‘Foliate’ timeline, detail

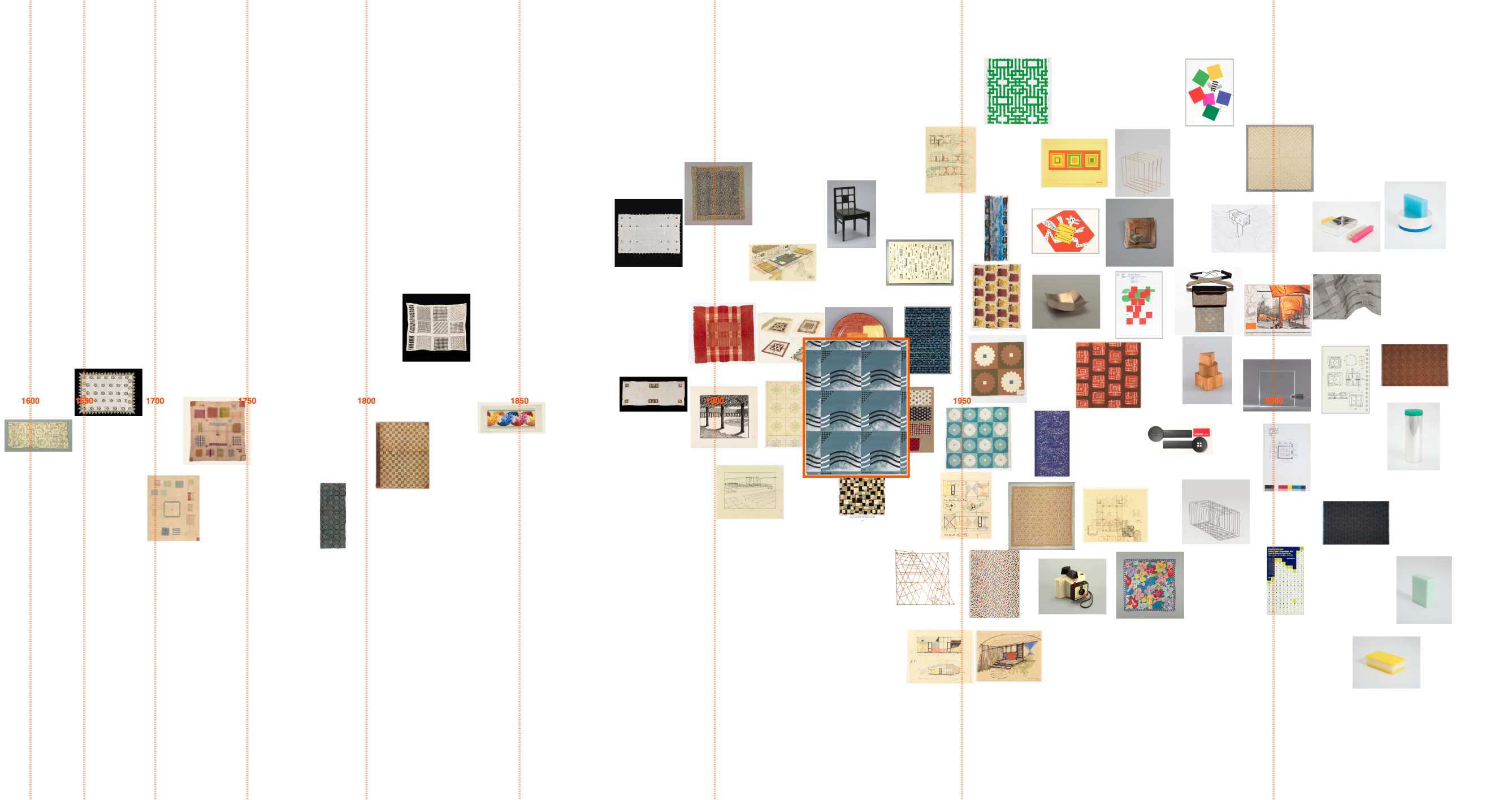

‘Squares’ timeline

‘Squares’ timeline

I’ve also tried to spread images out within date spans, rather than just use the central point, to avoid misleading shapes forming (such as a group of objects dating 18th century forming a column at the midpoint, 1750).

Things to think about

Interface design

- The layout algorithm slows when there are many (100 or more) images visualised. Is there a more efficient way to do this?

- I’m considering rotating the design 90° for web-use; I anticipate users will be interested to scroll along time, and scrolling vertically may improve usability with a mouse.

- Would a user be interested to see different timeline visualisations next to each other, to compare them?

- It could be interesting to apply this interface to other ways of grouping objects such as type, colour, country or other descriptor.

- I need to build in a back button, or some way to return to previously selected images. Maybe a search option for tags? Or a way to save images to return to?

Tags

- This visualisation design relies on curator-applied tags and, therefore, would be difficult to apply to other datasets: might there be a way to automate part of this? Maybe using computer vision technologies?

- Since objects are only tagged if they are featured in an exhibition, the interface misses many relevant objects in the collection when visualising a theme. For instance there are 23 objects tagged ‘Japanese’, but keyword searching the collection for ‘Japanese’ returns 453 objects. While the interface works well with the current quantities of images (up to about 100), what changes to the design would be needed to increase this number?

- What about grouping tags together? There is no dictionary or hierarchy to them so some are very similar, for instance: ‘floral’, ‘floral bouquets’, ‘floral swag’, ‘flower’, ‘flowering vine’, and ‘flowers’. Though it can be interesting to see the subtle differences in how related tags have been applied. For instance: ‘biomorphic’ is more often applied to modern objects; ‘nature’ is generally applied to depictions of nature such as landscape paintings; while ‘organic’ is applied in a more abstract sense to describe objects’ form.

I’m at a stage where I’d like to get user feedback from a range of audiences (general and scholarly) to explore some of these questions.

This is very much a work in progress, and feedback is welcome! (olivia.fletcher-vane@network.rca.ac.uk to get in touch by email)