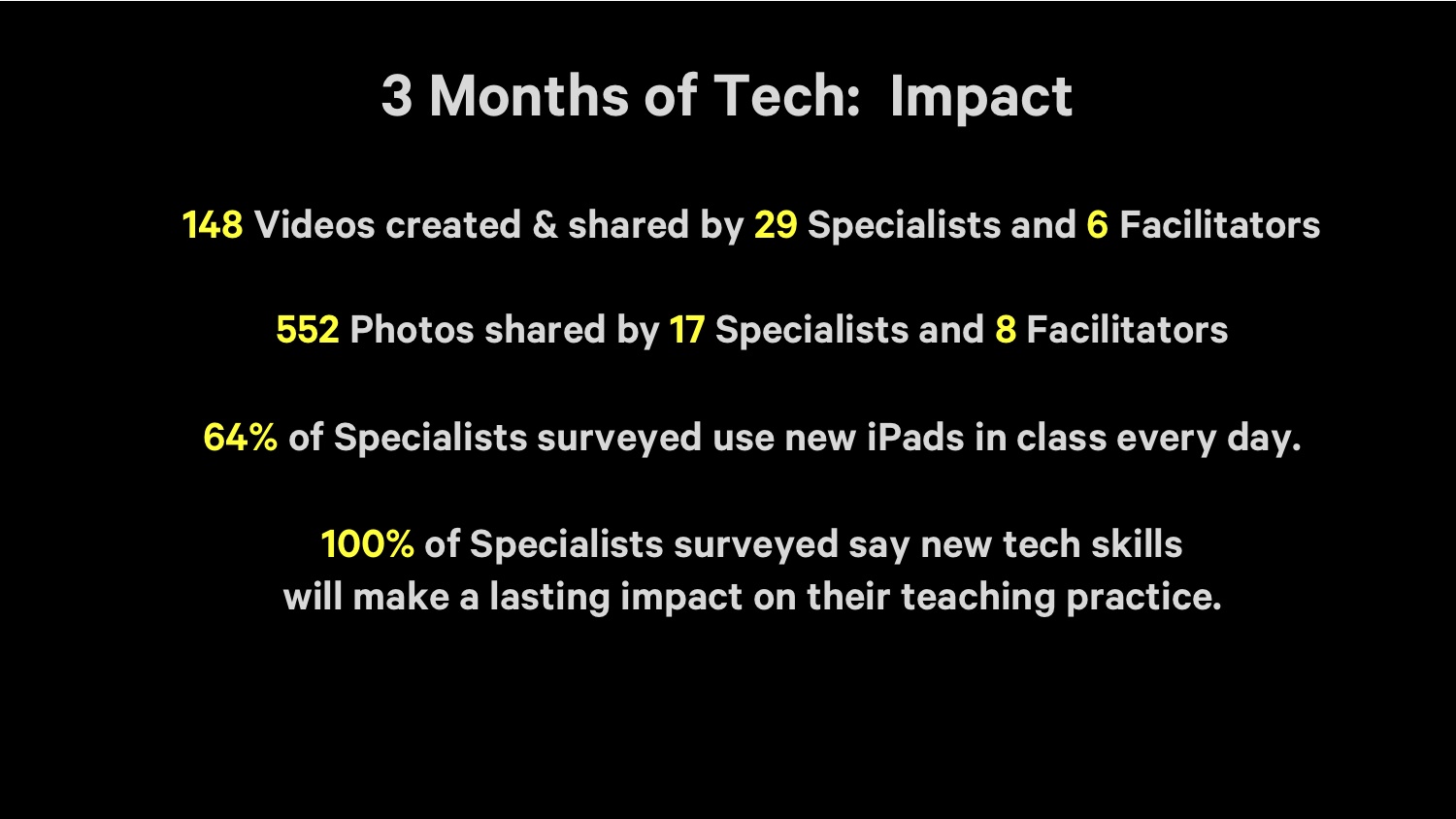

Labels, for better or worse, are central to the museum experience. They provide visitors with access to basic object information (metadata) and a tiny glimpse into the curatorial research for everything in the galleries, helping to place objects in context. At Cooper Hewitt, they are also the gateway through which the Pen‘s “collect” interaction is realized.

In order for the Pen to know which object label you’re trying to collect, every label in the museum contains an NFC tag that is written with the object’s ID. When an object gets added to our database we give it an ID, an integer that is unique across our entire online collections database. Our beloved Spanking Cat, for example, has the ID number 18382391. Writing that number to an NFC tag is a simple task, but doing it hundreds of times for every new exhibition we roll out will get tedious very quickly. Thus, Label Writer was born.

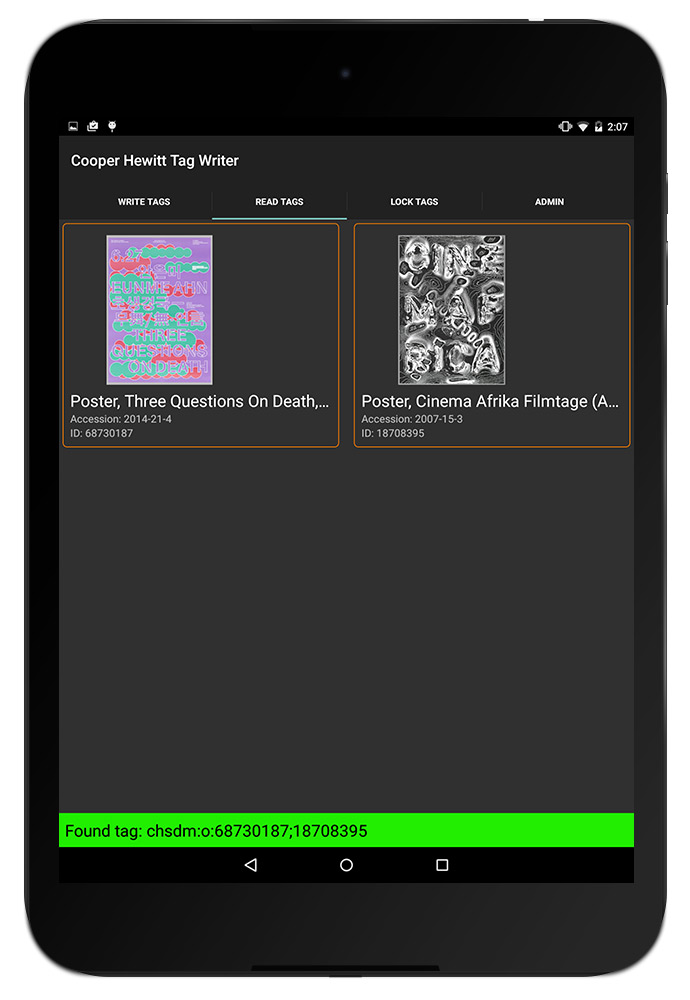

Label Writer is an Android app that writes, reads and locks NFC tags based on the object to which the label refers. The staff member can look up the objects that are in a given room of our museum, select one or more of them, and assign them to the label in question. They can search for specific objects in case an object’s location hasn’t been updated yet. They can also write tags for videos and shop items.

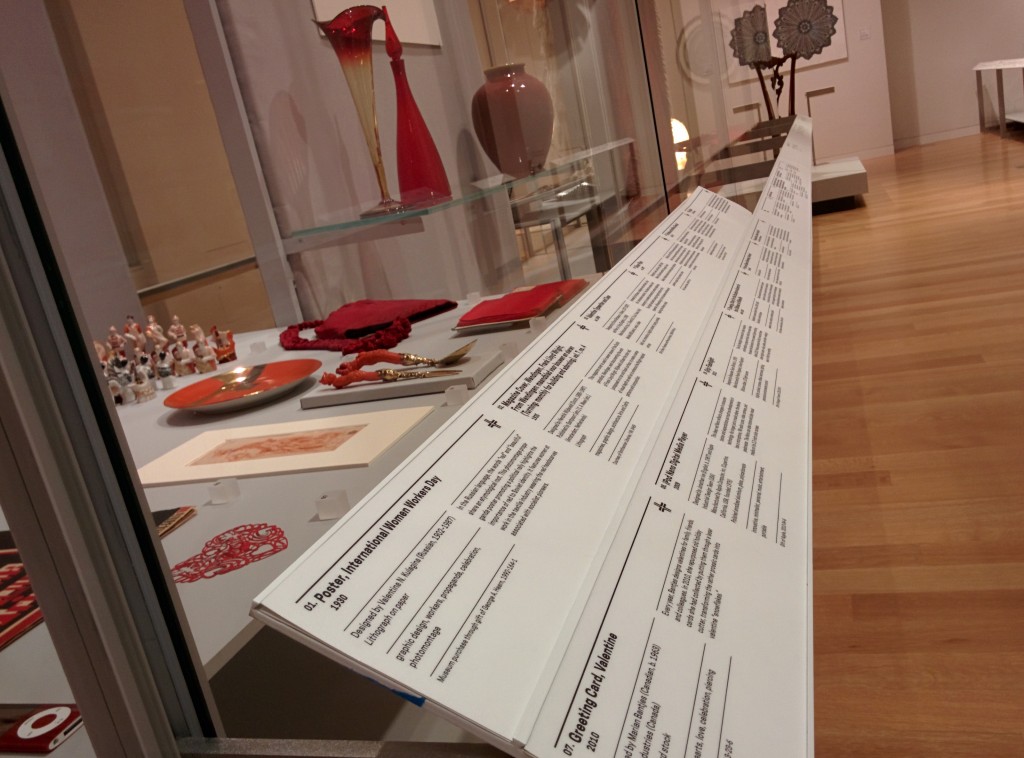

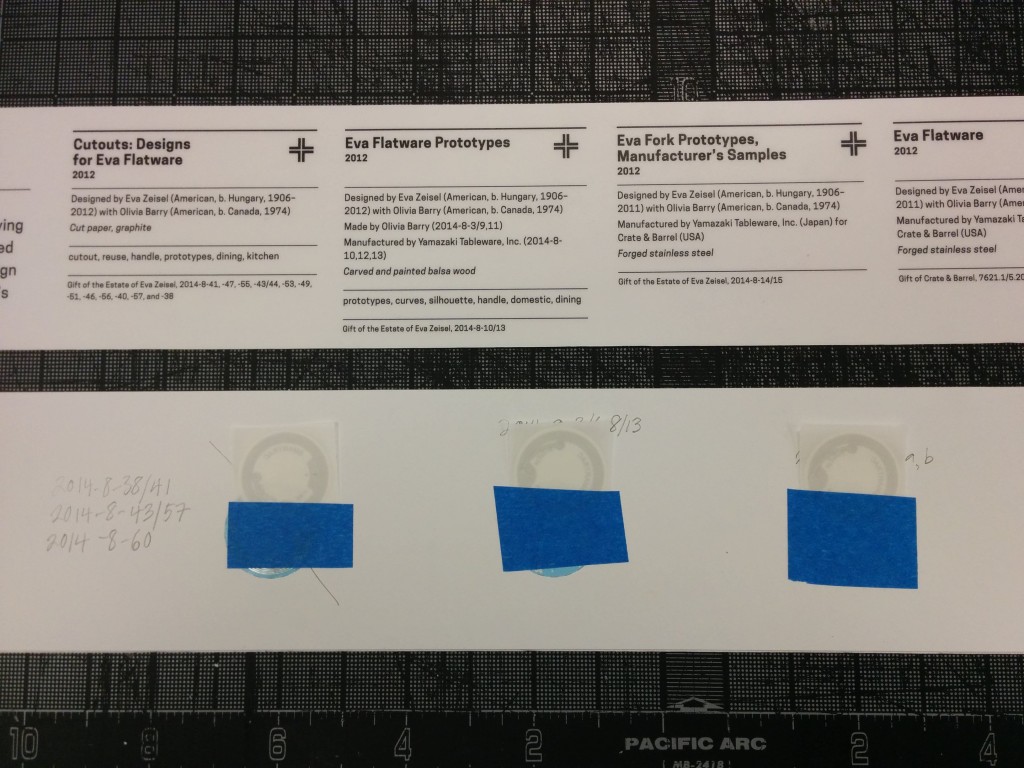

From left to right: the back and front of the NFC tags we use in our labels, and pennies for scale.

Planning

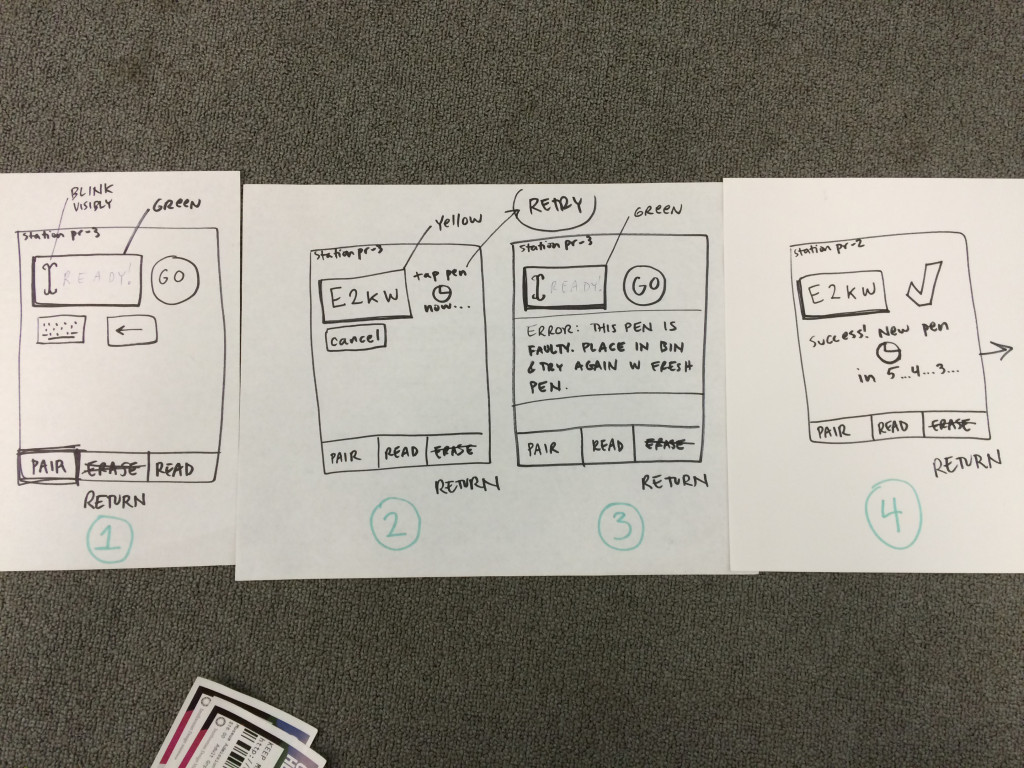

After thinking about the app we came up with the following requirements:

- When processing a user’s visit, we need to know what type of thing they’ve collected. When the Pen launched, this was either objects or videos, and has since grown to include shop items. To facilitate that process, Label Writer would have to distinguish between types of things and write tags that indicated that.

- It would need to write multiple things to a tag, including things of different types. One label might contain three objects. Another label might contain one video and two objects.

- It would need to lock tags. Leaving the tags unlocked would enable anyone with an NFC-enabled smartphone to walk around the galleries and overwrite our tags. Locking the tags prevents this.

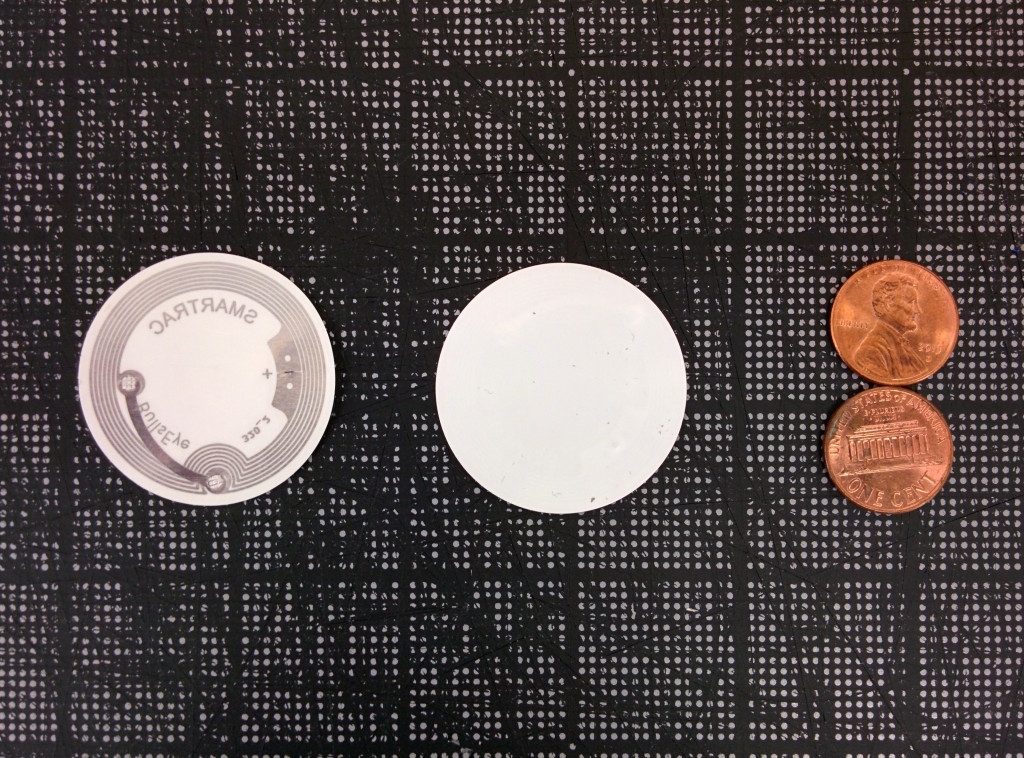

- It would need to read tags and display images of what’s on a tag. This is so we can double-check what is on a tag before we lock it. We only print one copy of every label – sometimes through an offsite service – and the wall labels (as opposed to the rail labels) have their NFC tags glued in and unable to be replaced.

- Label Writer would have to present objects in a constrained format — having to find the object on a label from our total collection of 210,000 objects every time, through accession number lookup or other traditional searches, would get annoying very quickly.

The NFC tags on our wall labels are built in to the label.

The NFC tags on our rail labels are interchangeable.

Production

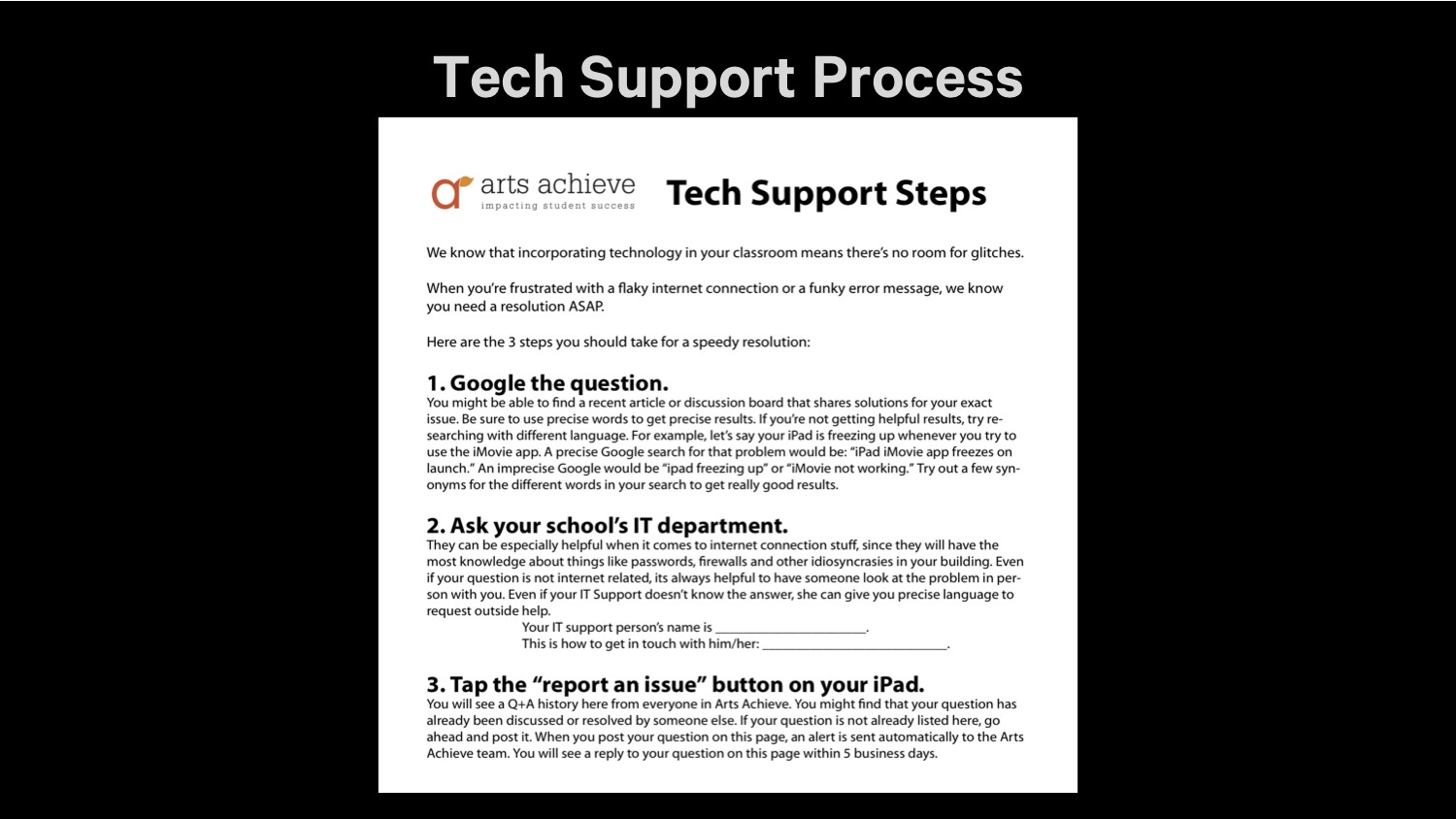

I decided to build the app in Android because it has great support for NFC and we have plenty of Nexus 9 tablets at the museum for use in the galleries. I started with this boilerplate for an Android read/write NFC app and performed initial tests to make sure we could write a tag that could be read by some of the early Pen prototypes. Once that was established, I began fleshing out the UI of the app and worked on hooking it up to our API.

The API gives us so much to work with on the app’s frontend. Being able to display an object’s image is a much better way to confirm that a label is written correctly than by comparing IDs or accession numbers. The API also lets us see all of the objects in a given room of the museum, which means that the user can write labels in an ordered fashion. When the labels arrive from the printer they are grouped by room, and often we will not write the tags until they have been installed in the galleries, so “by room” is a convenient way to organize objects on the frontend. It also gives us easy access to videos and shop items, and allows the app to easily be expanded to write labels for more things from our collections database. Since our collections site alpha, we have stressed the importance of an easily-accessed permanent ID for everything: people, objects, videos, exhibitions, locations etc., and now with the Pen we can prepare labels that allow users to collect any one of those things during their visit to the museum.

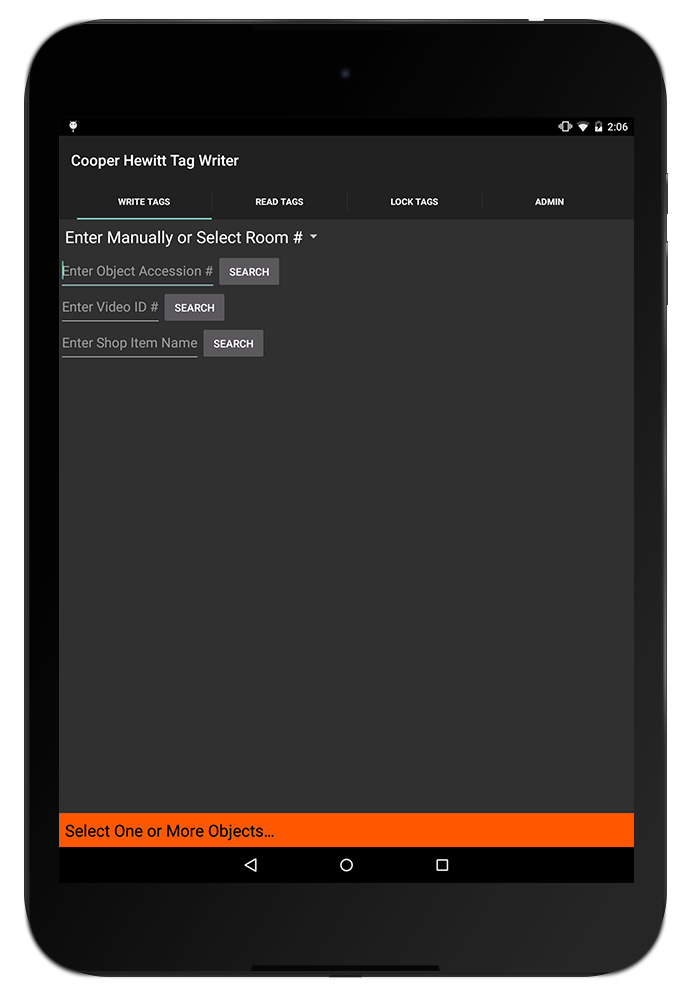

When I took all these screenshots, the app was called “Tag Writer”, as in “NFC Tag Writer.” But “Label Writer” sounds better.

When the app is opened, the user is prompted with a few ways to group objects. Since we added videos and shop items to the app, this intro screen has grown a bit so it will probably get a redesign when we next expand its capabilities. But for now, users have a few options here:

- They can select a room from a dropdown menu (here’s a list of all of our rooms)

- They can enter an individual accession number

- They can enter a video’s ID

- They can search the shop (see Aaron’s recent post about adding shop items to our online collection)

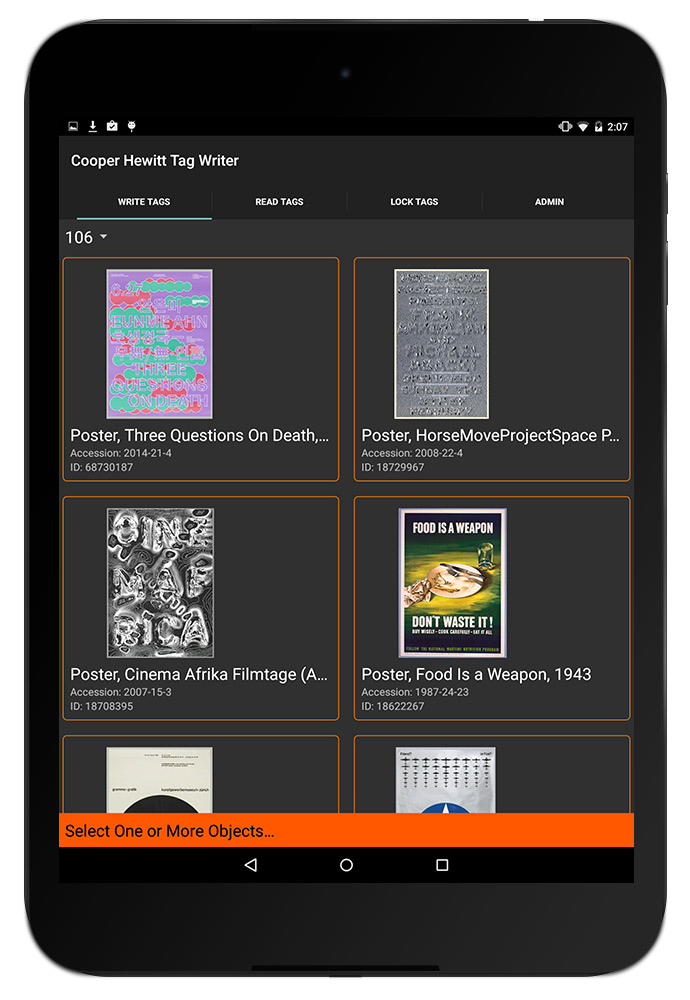

When one of these options is used, the relevant objects appear on the screen. For example, selecting Room 106 brings up some of the posters from our current How Posters Work exhibition. Being able to display the images of the posters makes it much easier for the user to confirm that they are connecting the dots accurately — accession numbers and object IDs are easily confused (not to mention boring to look at).

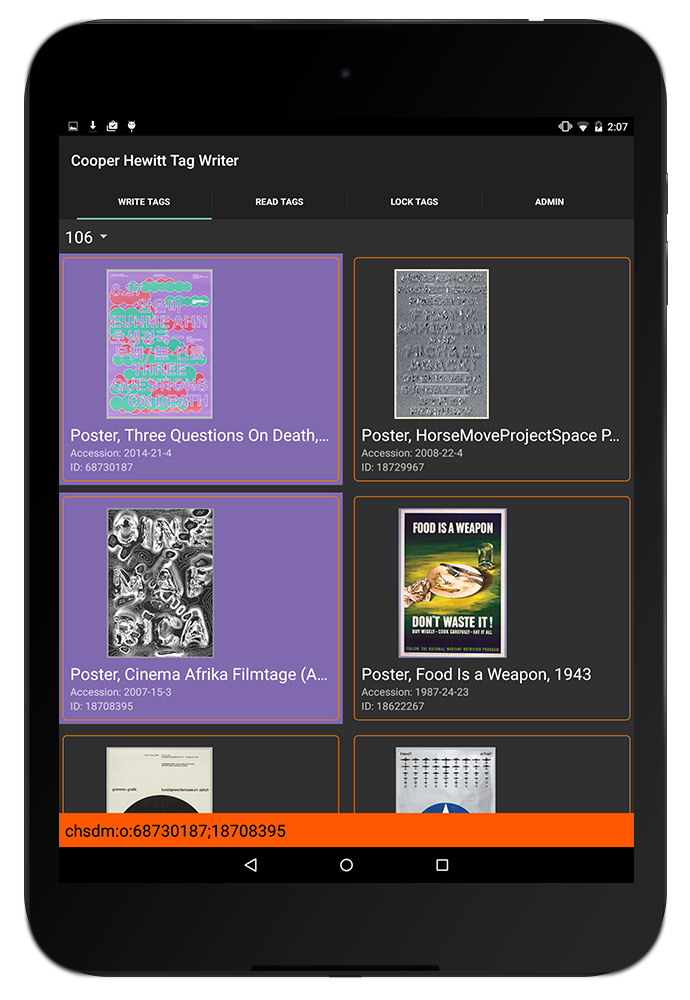

The user can then tap one or more objects to add them to a label. In the screenshot below, you can see that two objects have been selected and the orange bar at the bottom has formatted them to be written to a tag — in this case, chsdm:o:68730187;18708395. The way that things get written to tags follows a format we agreed upon early in the Pen design process, as various developers would be building applications that relied on reading and parsing a Pen’s content. In brief, chsdm is a namespace for our museum that is not particularly necessary but serves as a header for what follows. o stands for object and then the ID (or semicolon-delimited IDs) that follow are the IDs of objects. The letter can change: v for video, s for shop, and on and on for whatever other things we might eventually write to tags. We add a pipe character (|) to delimit multiple types of things on a tag, so a tag with an object and a video might look like chsdm:o:18714653|chsdm:v:68764195. But all of this is handled by the app based on what the user selects in the interface.

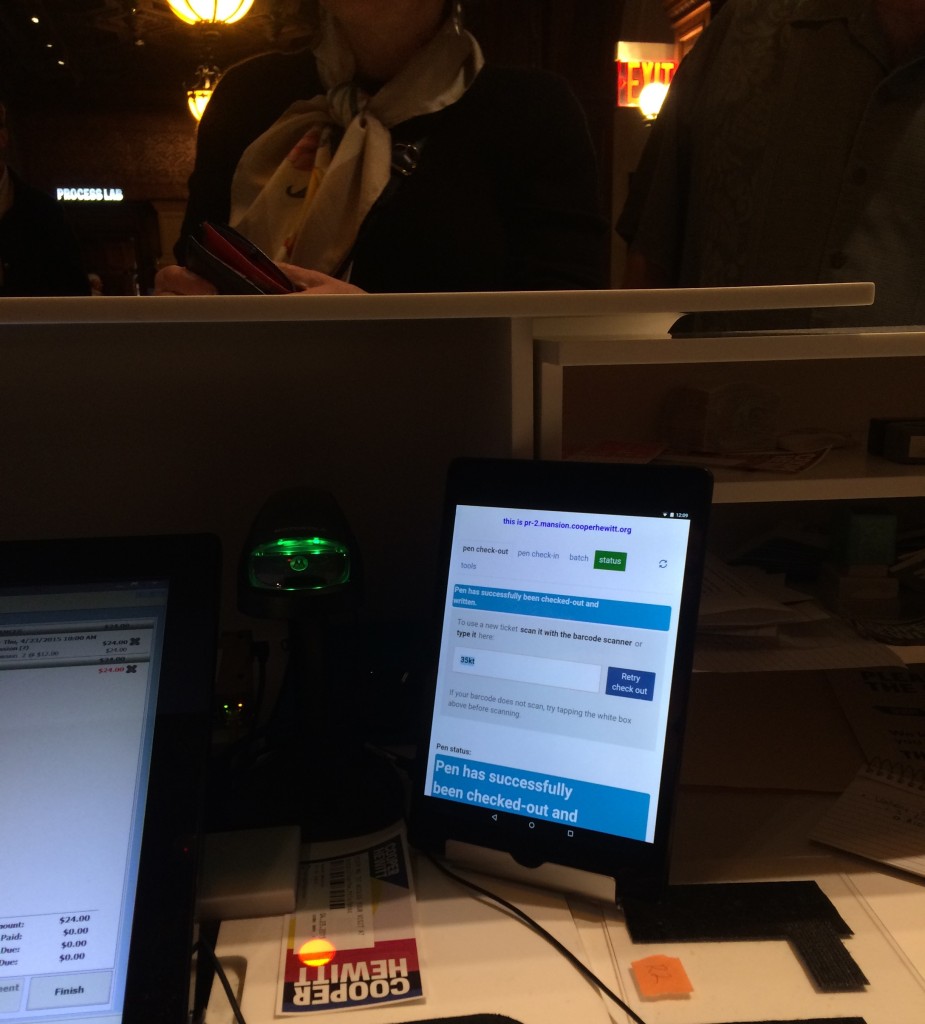

Next, a user can hold the tablet up to the object label to write the NFC tag. When the tag is written, the orange bar at the bottom turns green to let the user know it went okay. Later, using the “Read Tags” functionality of the app, the user can confirm the tag’s contents by reading the NFC tag. The app parses the tag and loads the things it thinks the tag refers to. When this is confirmed, the user can lock the tag to make sure nobody overwrites it.

Here’s everything, from start to finish, using the object-lookup-by-accession-number functionality.

Next Steps

I mentioned that the home screen of this app will get a redesign as we allow more types of things to be written to tags. The user experience of the tag writing process needs a little finessing — a bug in how success messages get displayed has resulted in a few tags that get written with bunk data. Fortunately that is caught in the “read” phase of the workflow, but should be corrected earlier.

Overall, as we keep swapping out exhibitions, Label Writer will get more and more use. We will use these opportunities to collect feedback from the app’s users and make changes to the app accordingly.