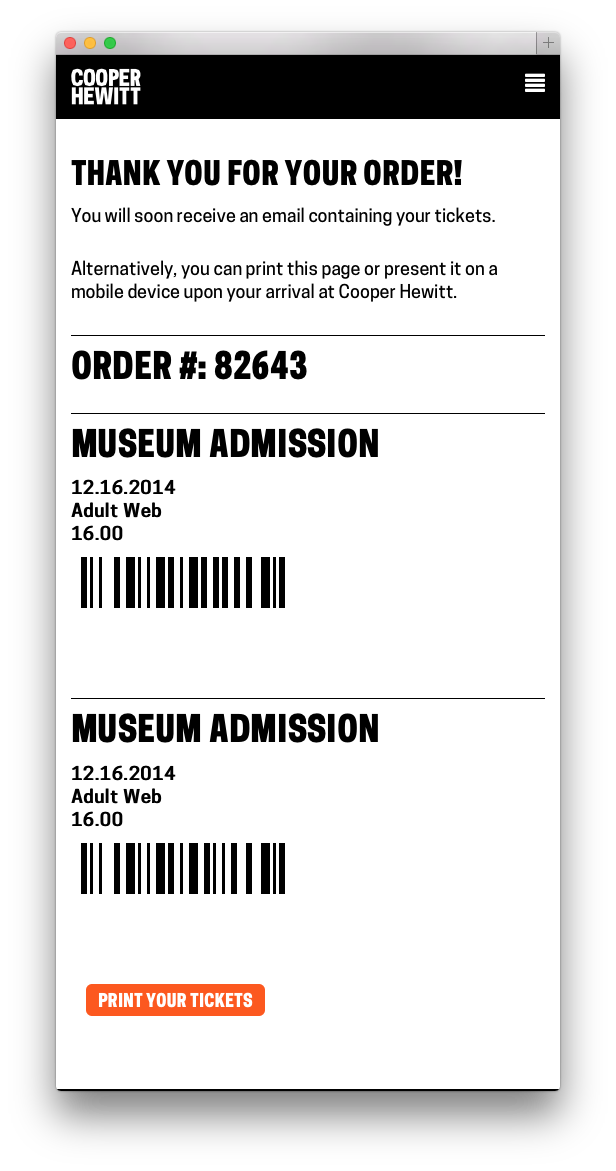

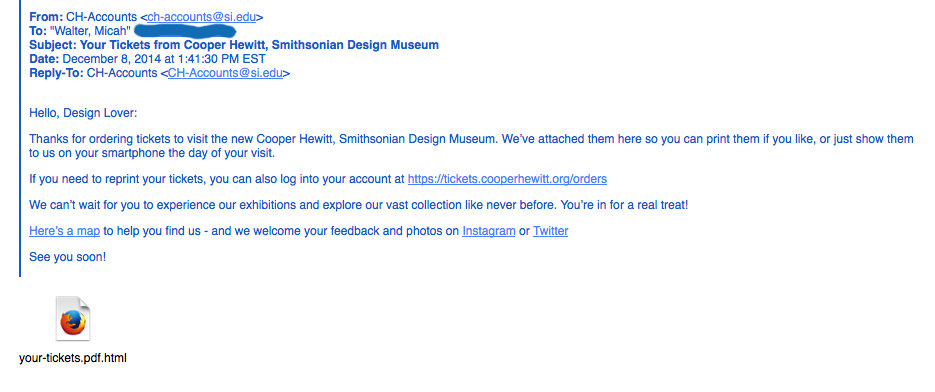

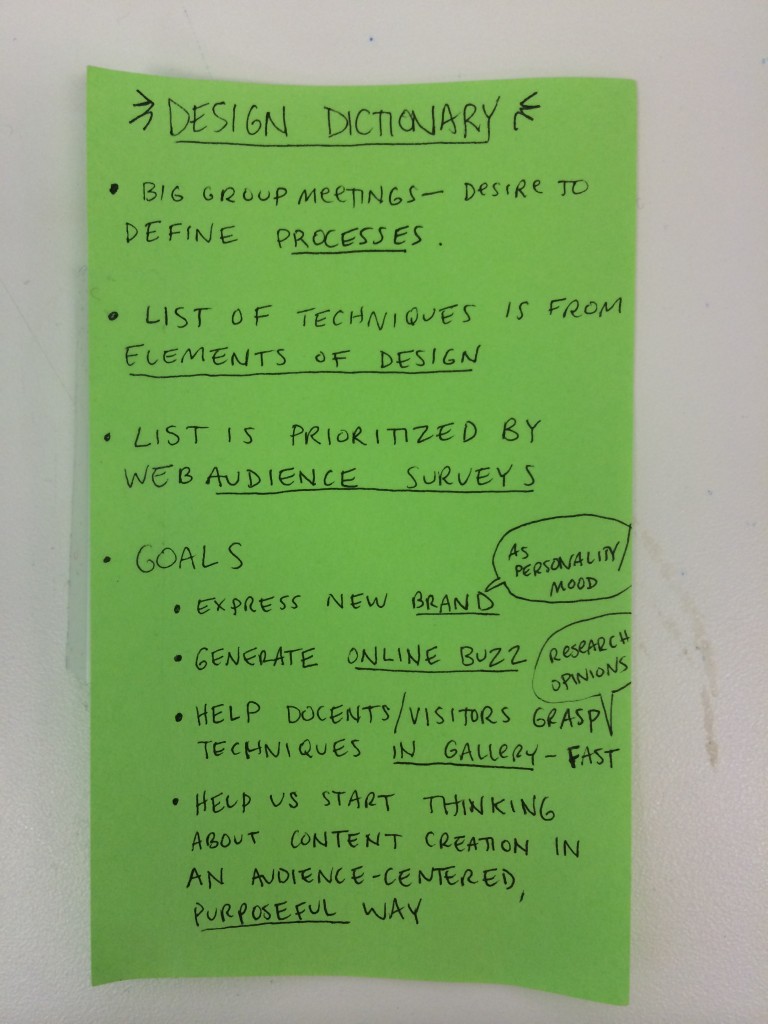

Earlier in this series I wrote about improving customer-facing ticketing touchpoints and UX improvements to a internal-facing app. This 3rd post is about the design and thinking behind a valuable— albeit non-tech— touchpoint: a postcard explaining how to use the pen.

When we first launched the Pen, it was obvious that we needed to quicken up the front desk transaction. One thing that was really slowing down the transactions (and causing a big line) was the “Pen schpiel.” A verbal explanation of what the Pen is, why it’s cool, and how to use it could hog up several minutes per transaction.

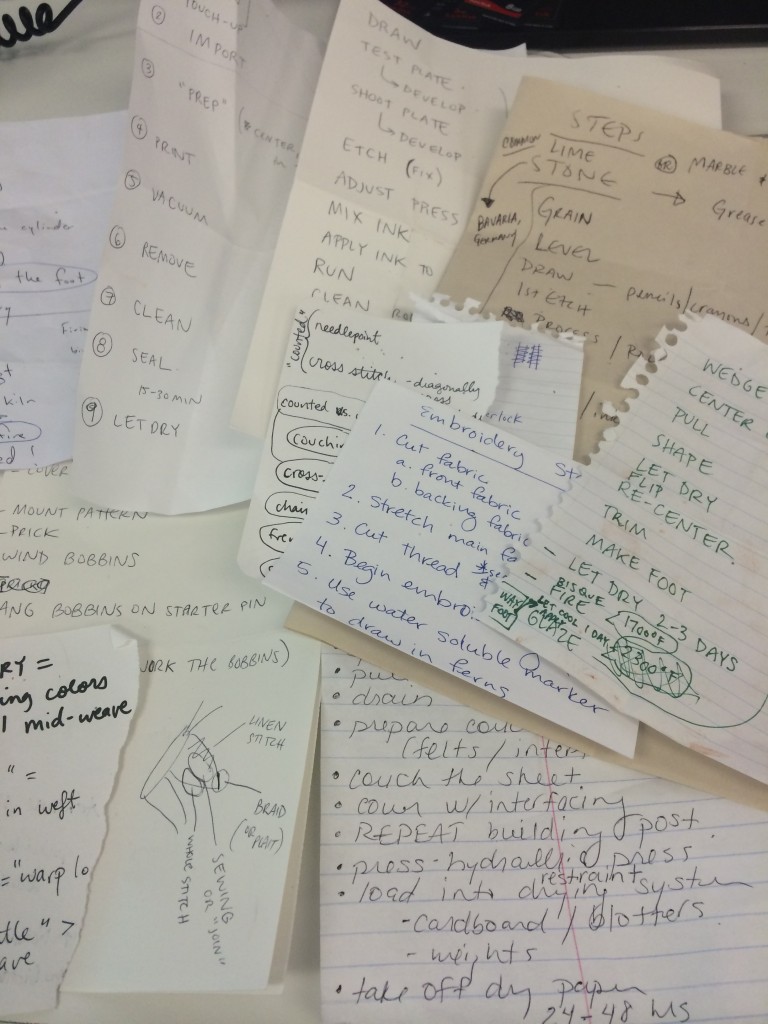

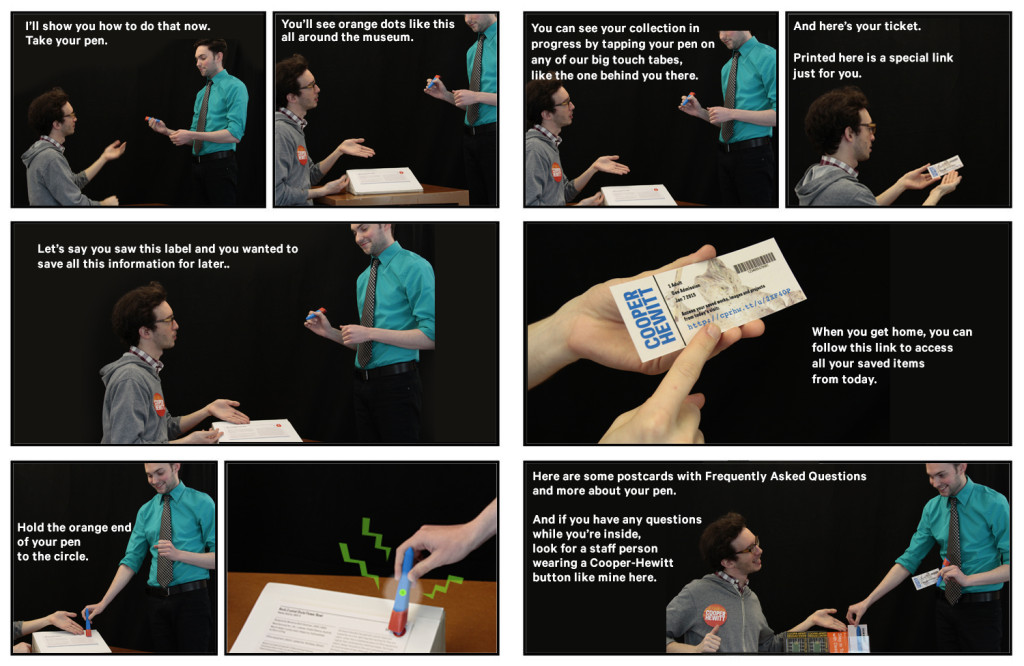

I made this storyboard in April 2014 with some willing coworkers and simple props (3D printed pen, fake ticket, fake postcard, fake “sample label,” and fake staff badge). In the last frame, the desk rep references an FAQ postcard.

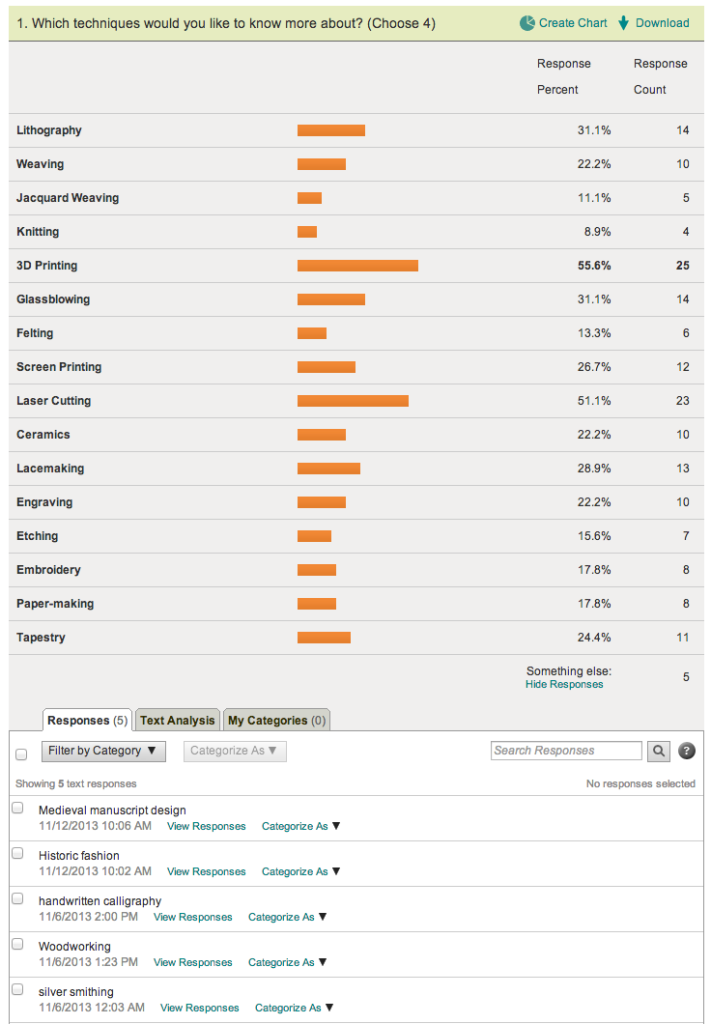

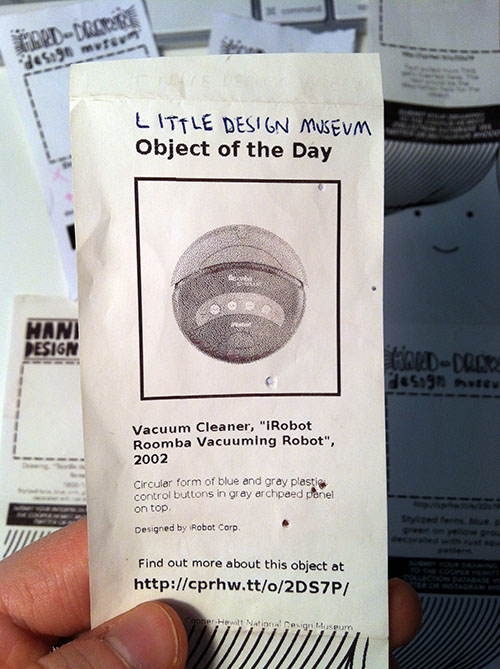

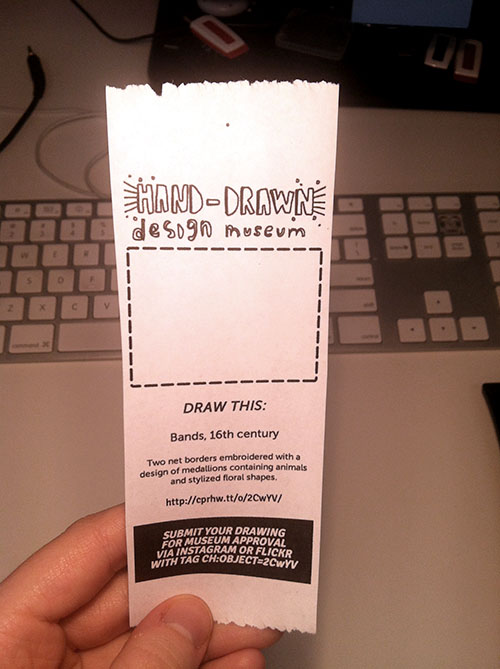

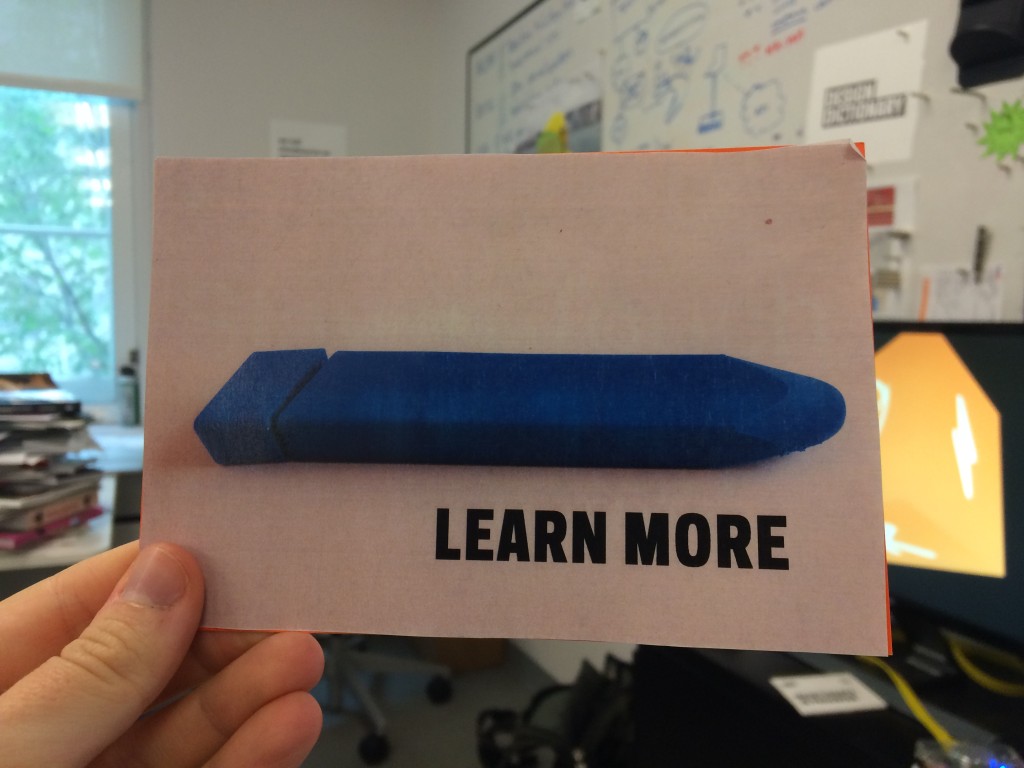

We predicted the need for a postcard almost a year before the pen launch, but didn’t print one until we were sure it was necessary. I mocked up a fake postcard with a photo of a 3D-printed pen to provide some needed conversation-starting visuals in our early meetings. This was long before the pen had a final form factor, and you can see that our initial conversations about pen size and shape were a little uncomfortable.

This was the ‘sample’ postcard in the above storyboard, all created months before the Pen had a final form factor.

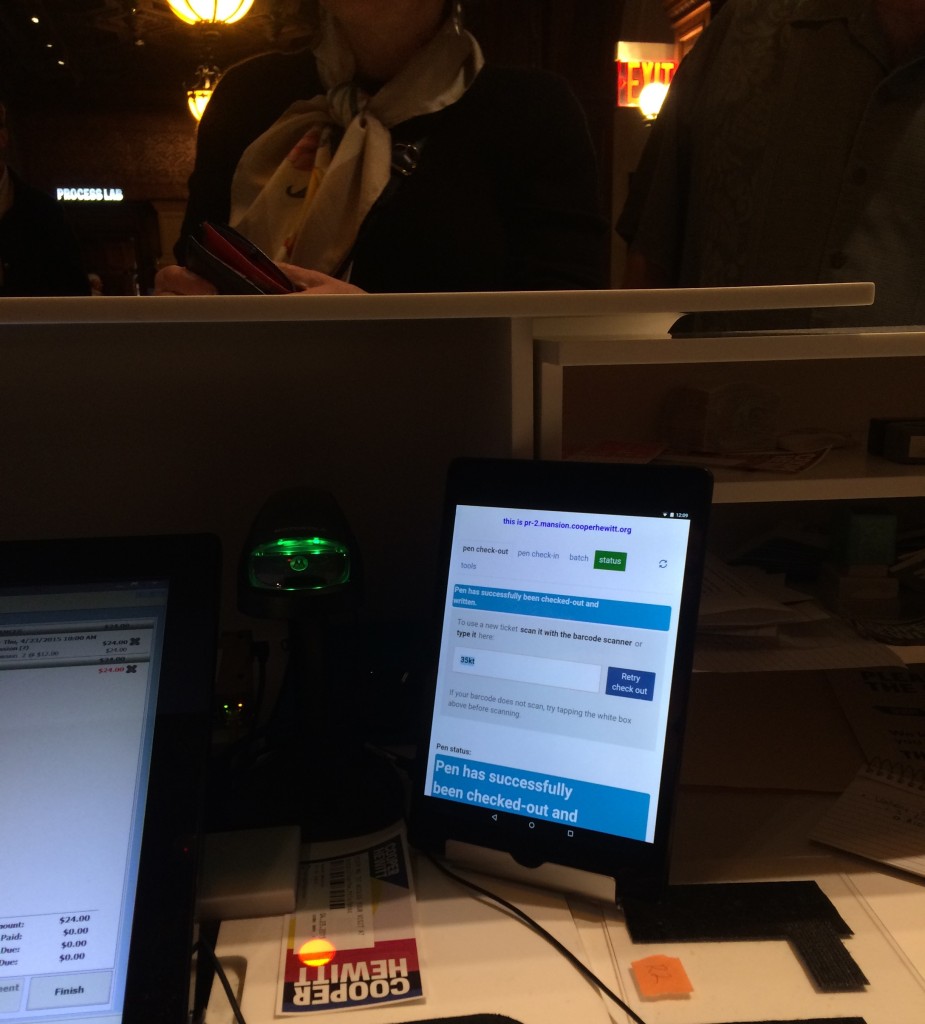

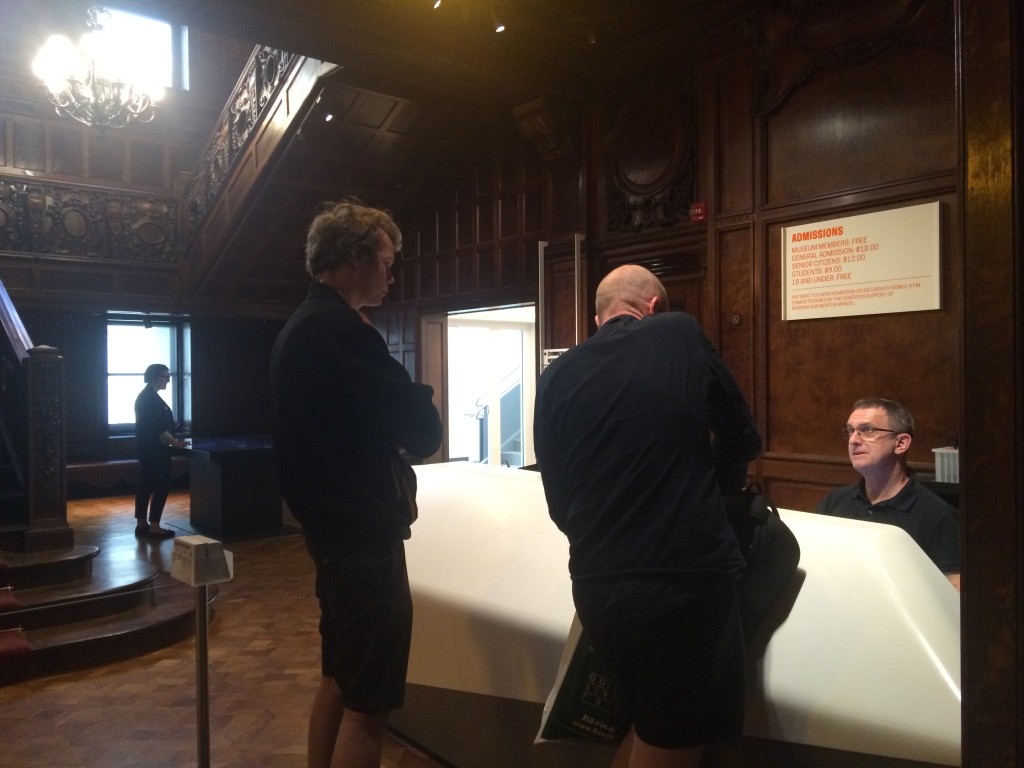

The postcard idea was on the back burner for many months as we all focused on the bare essentials of getting the Pen and its suite of services running at a baseline level. Once the Pen was released to the public in March 2015, the length of time of each transaction became an obvious “pain point” that needed our attention. So, the postcard was brought back to the table.

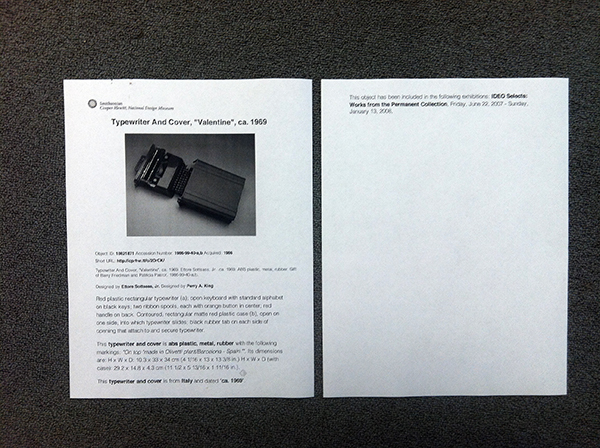

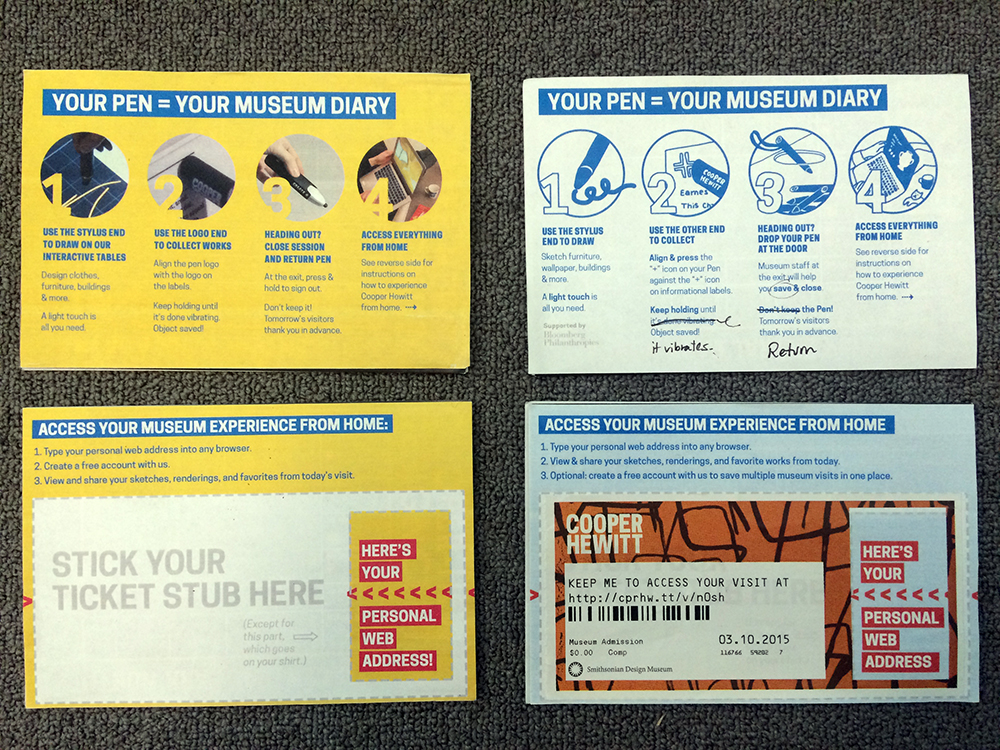

My first pass (left) used real images. The second pass (right) used illustrations, which were widely preferred by everyone I asked for input.

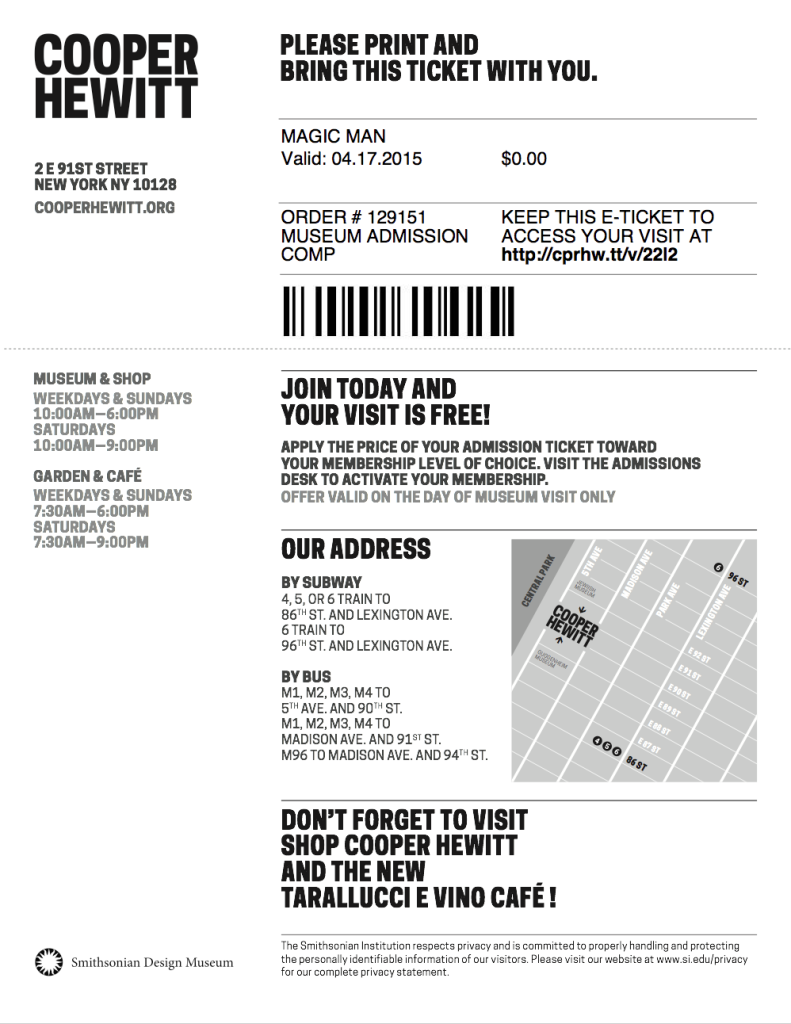

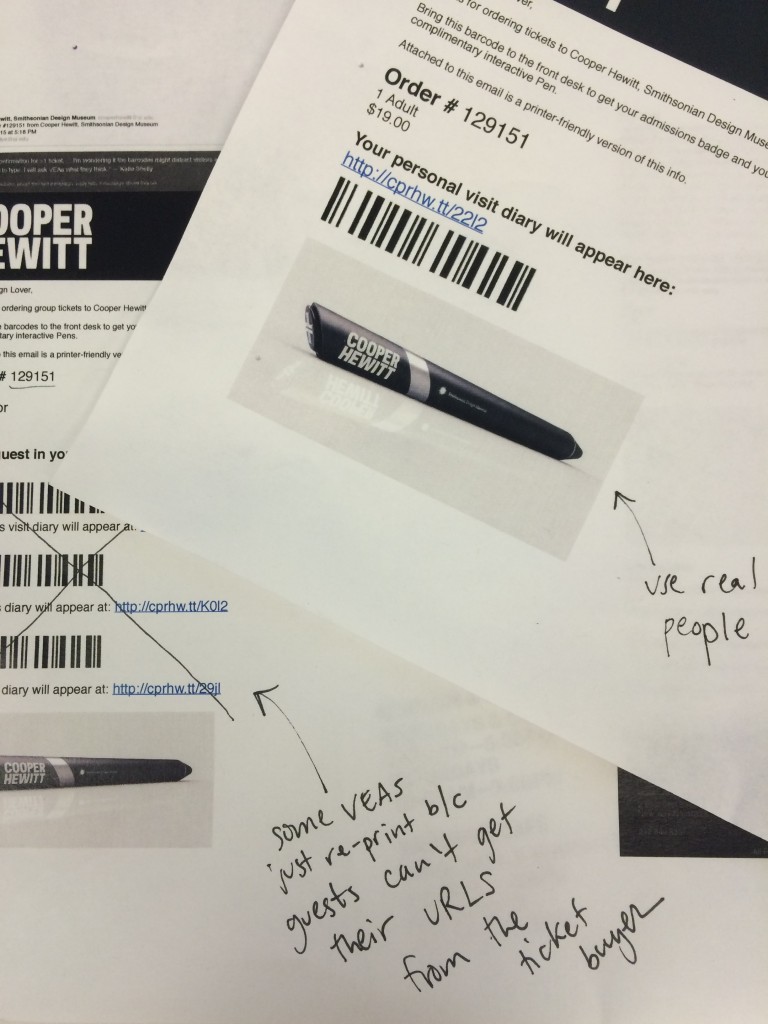

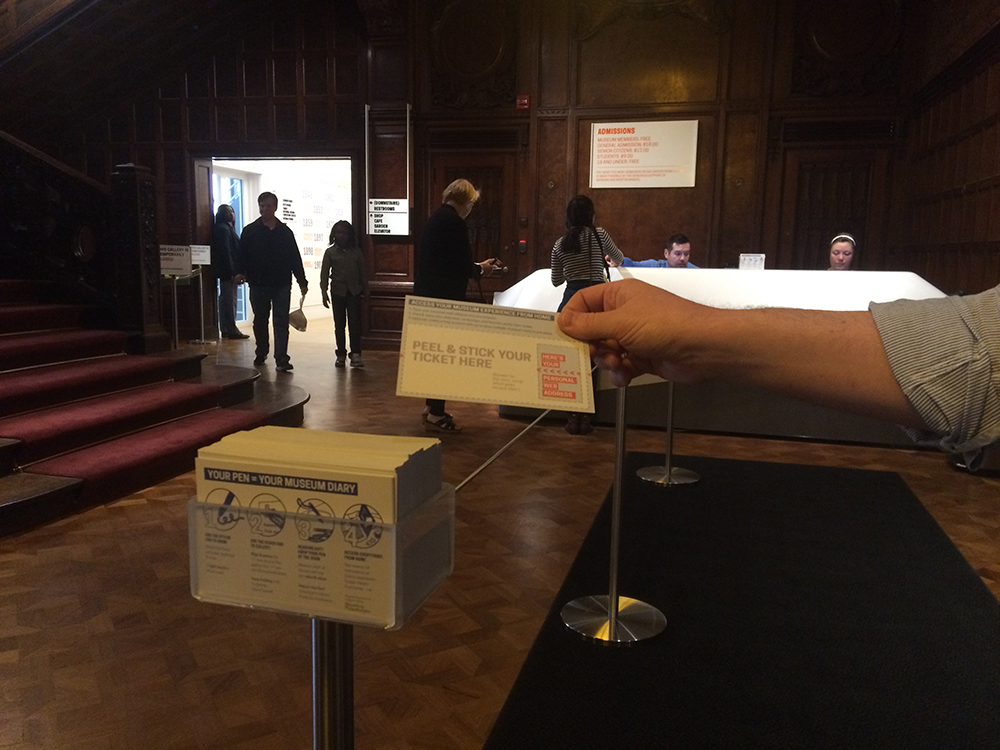

Sam had a cool idea to let visitors peel up the non-badge part of their ticket and stick it to the card, with some text boldly pointing to your “personal URL.” (The whole ticket is printed on sticker paper). This was clever because it could minimize the possibility of visitors losing or unthinkingly discarding their tickets, which contains the precious personal URL they’ll need to access their personal visit diary. When stuck to a postcard, the ticket might have a better chance of making it safely to a visitor’s home.

I worked closely with the front desk staff to get the language just right. It had to be concise but also explanatory. When the cards arrived from the printer, the desk staff was super excited and hopeful that these cards could help them save time and energy at each transaction.

The first printing of the pen postcard.

When put to the test, these postcards turned out to be less useful than we all imagined.

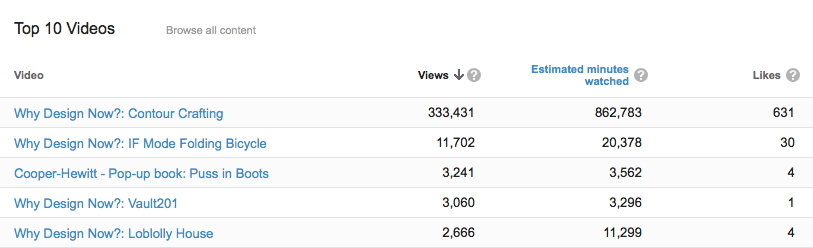

Only about 2 in 5 visitors wanted to take a postcard. And even the guests who did take a postcard still wanted verbal explanation in addition to the card. (We ended up handling this by diverting the most explanation-hungry visitors to a representative stationed at the nearest interactive table for informal “group tutorials”.)

So the postcard was not a panacea, but it did ease the pain somewhat.

There was an overall feeling from visitors and desk reps that the postcard was too verbose and this is why most guests didn’t want to pick it up and read it. Another point brought up by the desk staff was that while the card functions well as a didactic, it doesn’t sell the pen. It doesn’t tell you why you ought to try it. A third observation: most people were not springing for the cool peel-and-stick feature. Humbug.

People are more willing to read a document while they’re waiting in line than when they’ve reached the front desk and are already talking to someone.

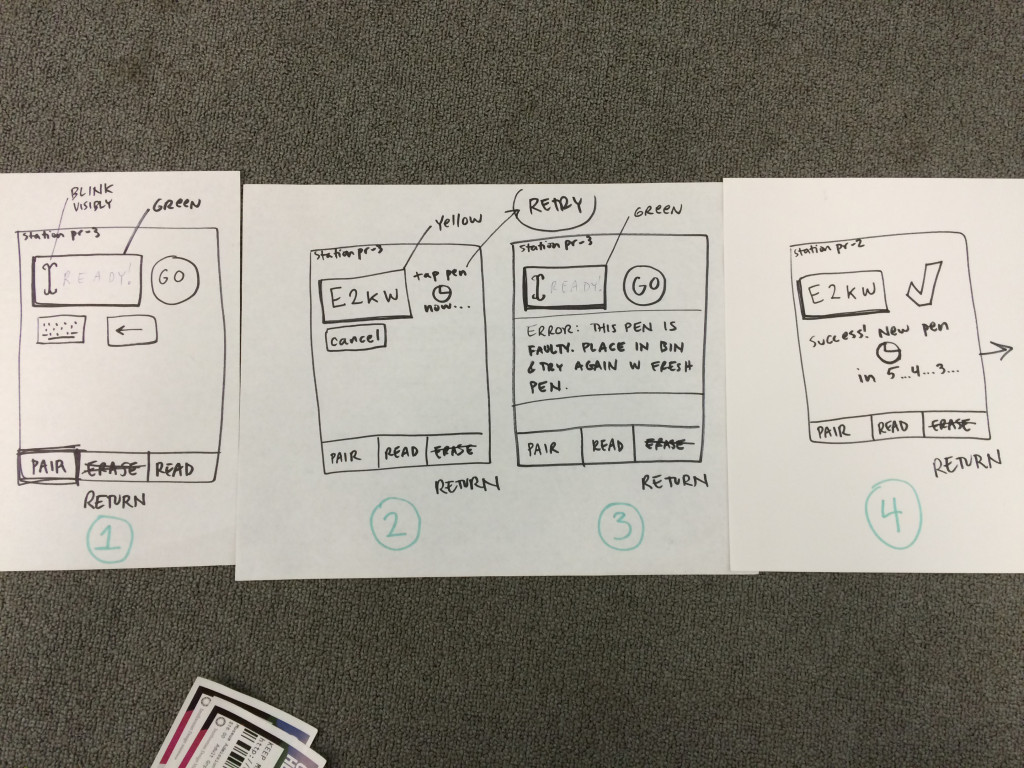

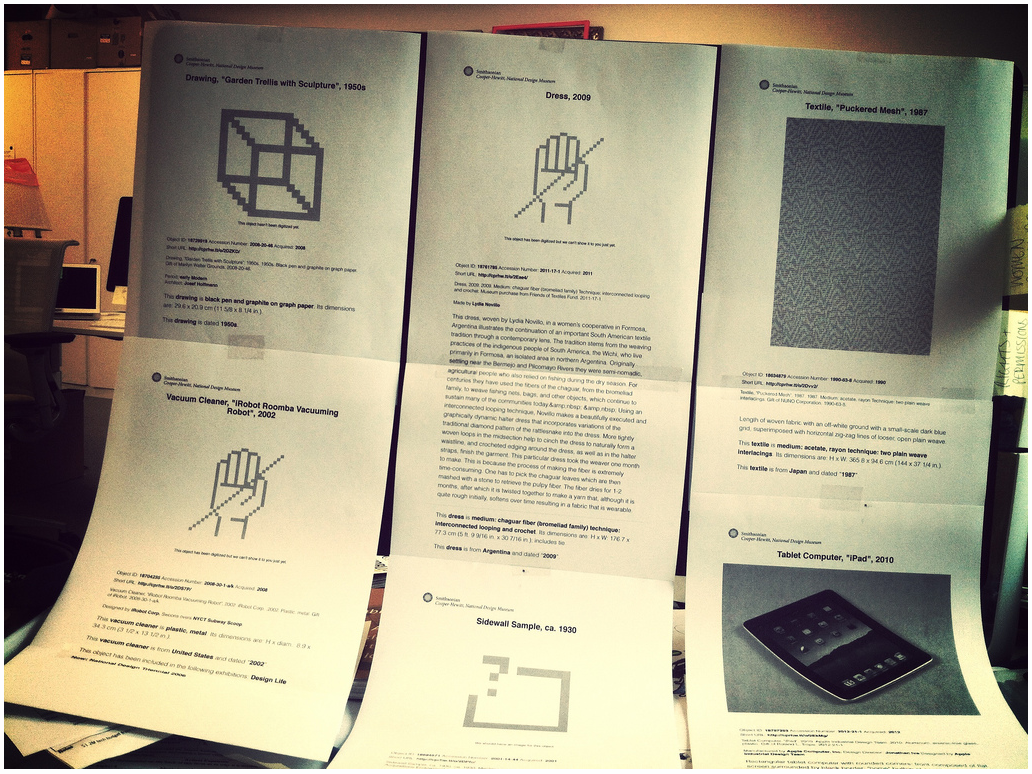

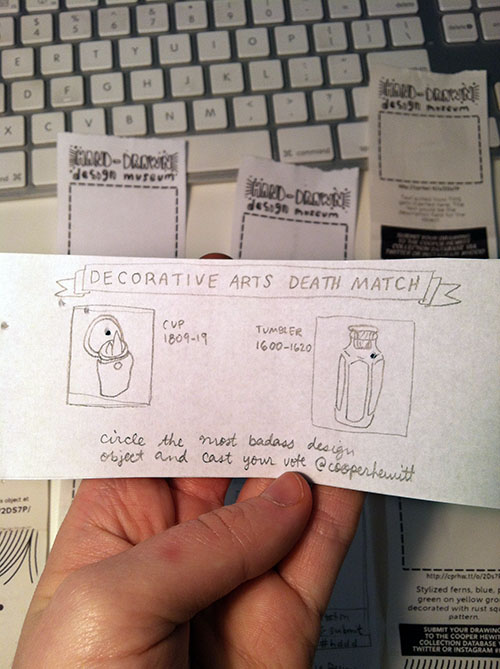

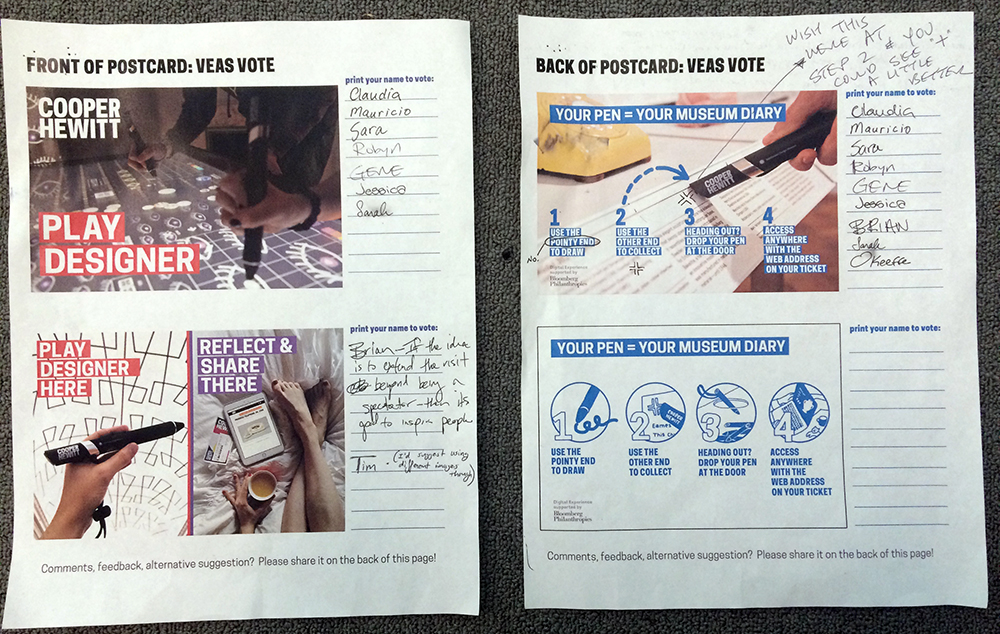

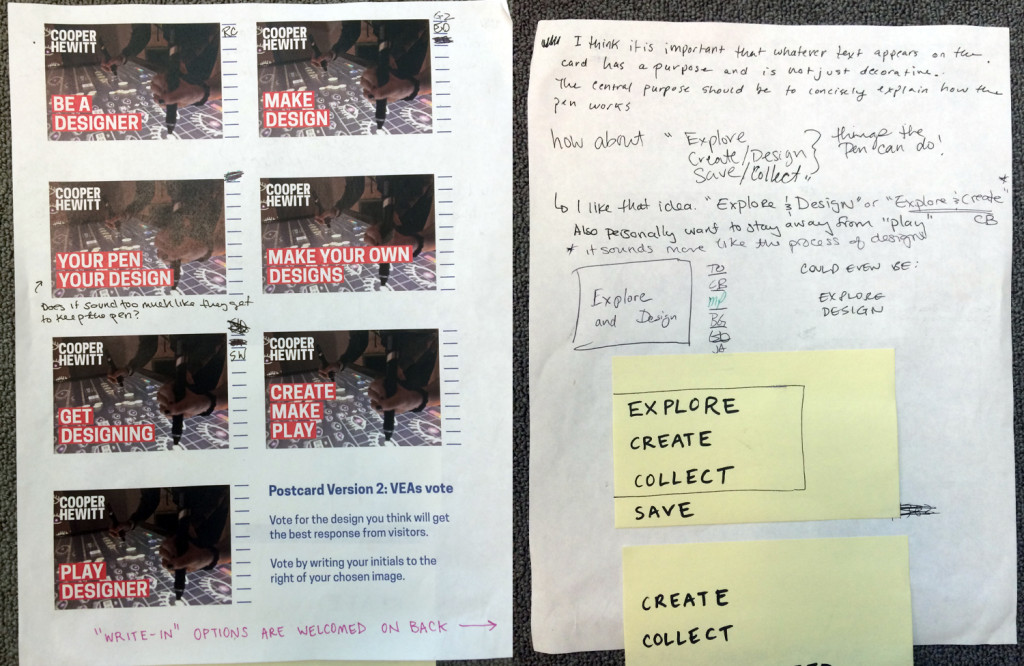

So we hit the drawing board again. I created a voting ballot so the front desk staff could weigh in on two choices for the front and back of the card. We had clear winners, as you can see in the image below. The voting sparked a conversation that led to further refinement of the text and images.

Desk Reps are always working on their feet or dealing with the public, so the most convenient way to get their imput is an old-fashioned paper ballot (not a web form).

The desk reps were unanimously against “PLAY DESIGNER” as sell copy for the Pen, because they were sure that many guests would think the word “play” meant the message was targeted at kids. So, I came up with 7 copy variations and we did another round of voting. The desk staff almost unanimously voted for a “write-in option” from one of their peers for its directness and clarity. The suggestion was: “EXPLORE AND DESIGN.”

The winning idea was actually a “write-in” contender on the back of the page, which sparked impassioned debate among desk staff.

The voting was not just a method for collecting votes, but also a way to spark conversation among many staff, across departments.

What I learned from this experience is that the folks on the “front lines” tend to dislike any language or collateral that is in any way subtle, abstract, or “overly clever,” citing the likelihood that too much coyness will just confuse visitors. It makes sense; when a visitor is trying to get going in the museum, corral his kids, juggle his bag and coat, get himself to the restroom, keep an eye on the time, and so on, he won’t have a lot of “brain space” for interpreting any subtleties. They just need crystal clear information to get them on their way.

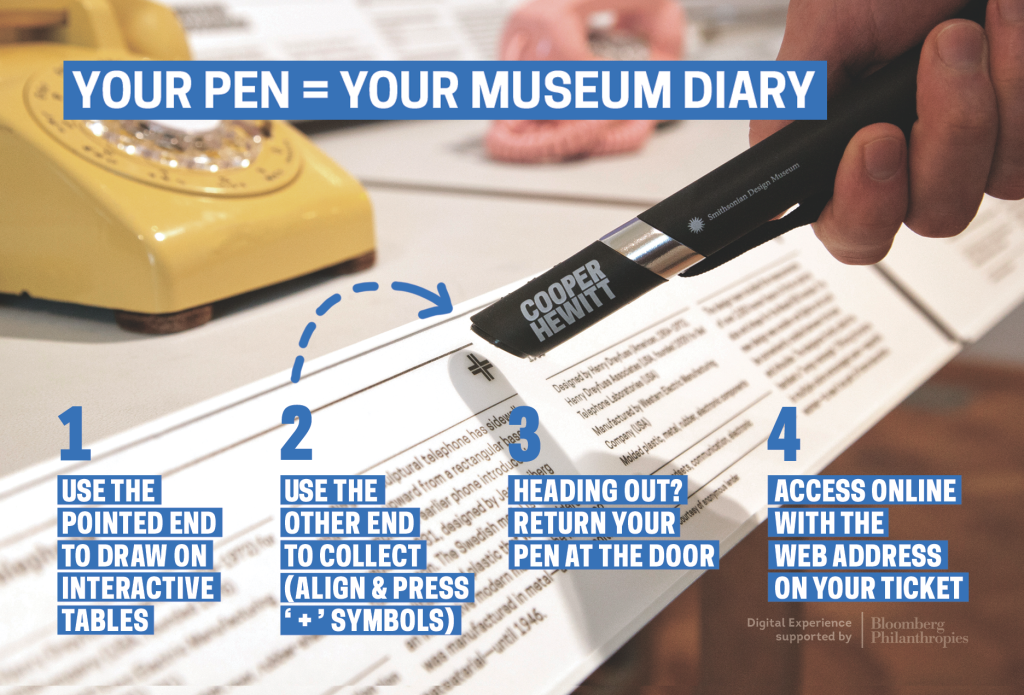

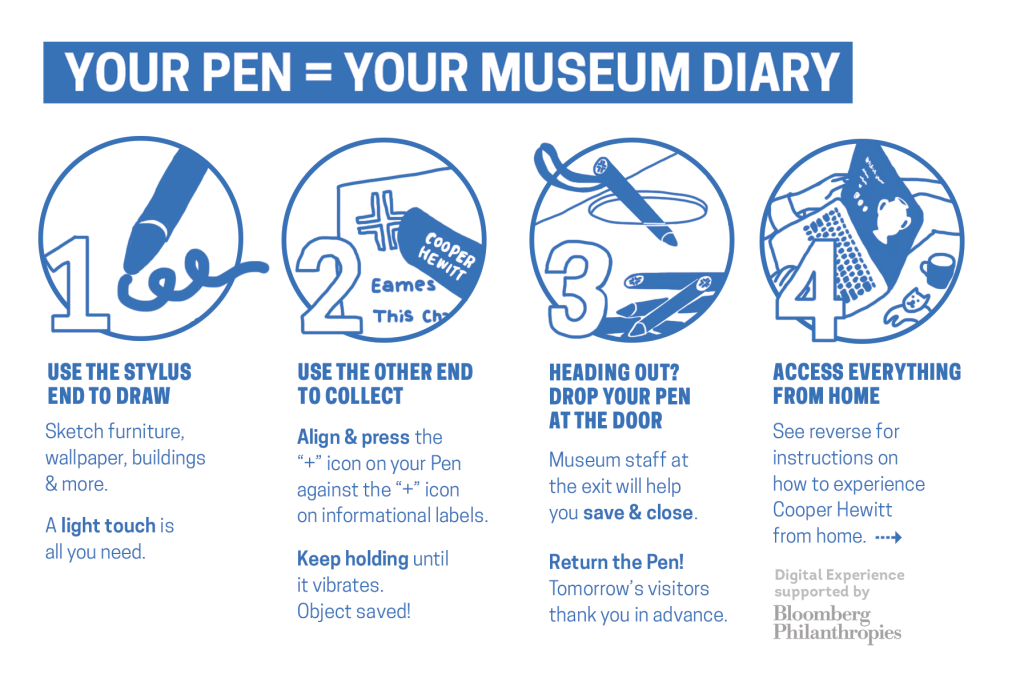

The new postcard shows real people using the pen, making it visually obvious what a person should do with it.

The second version has:

- Giant copy to “sell” the pen by describing its basic functions (Create, Collect, Save).

- Bigger images to catch attention and make the card more “pick-up-able.”

- Less text to ease tl;dr anxiety.

- Image and word choice is intended to make the function of the pen’s “tip” and “base” obvious just by looking.