This is the third in a series of three “adventures in universal design,” a design research experiment carried out by Rachel Sakai and Katie Shelly. For an introduction to the project, see our earlier post, here.

SHADOWING:

OBSERVE LINDA & DAVE AS THEY VISIT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

AUGUST 22 2013

On the Science Sense tour, we met a wonderfully friendly and warm husband and wife duo named Linda & Dave. We asked if they’d be interested in volunteering for some more research by allowing us to shadow them at any museum they chose.

They agreed, and a week later, off we went. Linda is blind and Dave is sighted. They love museums, and they have visited many around the world, together.

Here’s a play-by-play of their visit:

-As we entered the crowded lobby, I noticed that Dave firmly placed his hand near the back of Linda’s neck to guide her—it was so crowded and loud, he had to use firm physical contact to help her navigate the security bag check and chaotic lobby. Linda also used her rolling cane in her left hand.

-Once we got inside, the first thing they did was go to the information desk and ask how to find the exhibition they wanted to see—Brush Writing in the Arts of Japan. The desk person indicated the location on a paper map. L & D didn’t use the map; instead they listened and remembered the attendant’s verbal instructions (left at the arch, elevator to floor 3, make a left, etc).

-Linda carried a paper flyer in her purse with a list of special exhibitions on it, and she brought it out when talking to the attendant, saying “yes, we want to see the one on this list.” Interesting that though she herself could not see what was on the paper, she knew what it said (ostensibly because Dave had told her earlier) and she kept it in her hand, so she could use it later when conversing with others.

-On the way to the elevator, we walked past a table with audioguides, L&D did not notice it.

-At the top of the elevator, we saw an Information Desk with an attendant. Dave expressed excitement that they have Info Desks throughout the Met, saying “before they had these things, I would just wander around this place getting lost!”

-L&D approached the satellite info desk, and asked about the acoustiguide— does it include the Japanese Brush Writing exhibition? The attendant explained that the audioguide covers the whole museum. Audioguides are not being given out from this desk, though. L&D did not get an audioguide.

-We walk down a hall full of artifacts toward the Japanese Brush Writing show. Dave went into “concise tour guide mode” just to give Linda a sense of the scenery, simply naming a few of the objects we went past: “Perfume bottles.” “Ceramic horses.”

-We found our destination: a dimly lit gallery. Linda asked, “is it all paintings?” And Dave explained that no, the gallery had a combination of statues, ceramics, and scrolls. They were pleased that there was a variety of objects and it wasn’t all flat work.

-L&D approached the standing warrior statue at the entrance of the show. Dave began with a visual description of the statue— materials, colors, posture. When talking about the statue’s long earlobes, he lightly tugged Linda’s earlobes. When talking about the statue’s tufty hair, he lightly touched the crown of Linda’s head— anything to make the experience more than just standing and listening. After his thorough description, he read the object label aloud.

-They were very methodical. This is what they did in front of each object they looked at:

1) Dave gave a purely visual description. Colors, size, subject matter, mood.

2) Maybe a few clarifying questions from Linda (“Are the lines roundish or squarish?” “Are the lines harsh?” “Are the people done finely?”)

3) Dave read the object label aloud, sometimes omitting a bit of info, sometimes reading it all right down to the donor details.

4) A bit of back-and-forth, sharing their reactions to the piece, making a connection to prior knowledge or experiences, or simply expressing how pretty and/or interesting they find it.

In front of this artwork, Dave guided Linda’s hand through the air to help explain the size and composition. (It looks a bit like she is touching the artwork because of the angle of this photo, but we assure you that she is not).

-Dave often would take Linda’s hand in his, hold it outstretched, and wave it around to delineate shapes and spatial relationships (“there are mountains here, and a waterfall right here…”)

-A few of the Buddha statues were doing mudras with their hands. Dave would put Linda’s arms and hands into the same position, mimicking the statue. Sometimes he’d join her in the pose, so they’d both be frozen, holding the pose for a moment of contemplation. (Extremely adorable.) I don’t think many sighted visitors would think to do this, but it looked like they were having fun, and perhaps gave them a bit of “somatic insight” into how that statue might be feeling.

-As Linda got more details about the piece in front of her, she would exclaim surprise, “oh!” “oo-ooh!” As if she was building an image in her imagination, and each new bit of info from Dave was like an exciting clue in an unsolved mystery.

-I noticed that sometimes Linda would touch the glass in front of an object. Just to get some sense of space and anchoring, I’d guess.

-About halfway through the exhibition, Dave took a break to sit down on a bench. Linda, Rachel and I took the chance to chat a bit. Linda commented that she would like to get a sense of scale and mood upon entering a museum. A sighted visitor gets a whole bunch of scene-setting information right upon entering with a sweep of the eye, and can choose what piece they want to check out. For her, however, she’s generally subject to Dave’s decisions about what to look at when they tour an exhibition. She said that she doesn’t mind this, because she likes Dave’s taste, but it is a consideration for any blind visitor.

-From Dave’s perspective, it’s a lot of talking and mental work. He seemed to be a bit worn out at times when reading aloud those long object labels. No wonder he needed a break!

-Linda also mentioned that they like to go to the gift shop, and that sometimes there are statuettes or replicas of things in the exhibition that you can touch, so that’s a good blind person’s “hack.”

Hacking the museum: the gift shop is a good place to find touchable replicas of objects in the collection.

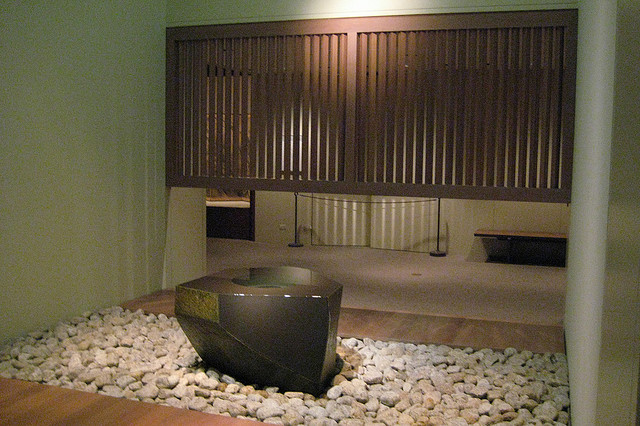

-As we moved on, we neared a fountain. Right away, Linda heard the water trickling and said, “I hear a fountain!” Dave started to describe the fountain, which, as it turned out, is kinda hard to describe in words. There were some children seated on the wooden platform beside the fountain. Linda asked if she could sit down on the platform, which is somewhat bench-like, but sort of ambiguous-looking as to whether you can sit there or not. We said, sure, go for it. One thing led to another.. and soon Linda was feeling the white stones, and then the fountain itself. There was no guard in the area, just a few fellow patrons who seemed touched and tickled, as were we, watching Linda light up as she discovered the different textures and shapes. “Ooooh!” “Ahhh!” “Wowww!!” She was so, so into it. Just totally beaming. Finally, something to touch! Dave turned to us with a wink, and said “See what a difference tactile makes?”

-Our last stop was a Japanese Reading Room, where the museum has tea ceremonies and other social events. The room has some Japanese-style floral arrangements, and beautiful wooden furniture by George Nakashima. Linda gave herself a thorough tour of the furniture, feeling the curves, bends, and joints in the massive walnut table and matching chairs. since it was definitely OK to touch. It was really the only moment when Linda could be independent in the museum.

Takeaways

– Linda & Dave had carbon-copy experiences. Many people enjoy visiting a museum with a partner and staying side-by-side the whole time. Sometimes, though, you don’t want to visit in that way. Personally, when I’m in a museum, I tend to break off from the group and explore on my own. How might we allow blind visitors to have the option for an independent experience?

– Sighted visitors can easily get a sweep of the room immediately upon entering. What looks interesting in this gallery? What’s the mood? Where do I want to go first? How might we afford blind visitors a “sweep of the room” upon entering?

– Linda pointed this out to us during the tour: neutral description > coded description. A neutral (and blind-friendly) description would be, “on the left there is a small, simple building with a thatched roof and open balcony on all sides.” A coded (and blind-unfriendly) description would be “on the left there is a small building, looks like early Japanese architecture.” Get the difference? A neutral description uses transparent language that requires a minimum amount of previous knowledge. A coded description requires some prior education or knowledge to understand it.

– Tactile makes a huge difference. Tactile moments were highlights of the tour: Dave tapping Linda on the head while describing a warrior’s messy hairdo, Dave sweeping her hand around to convey space, folding her hands into a Buddhist mudra, Linda tapping the glass in front of her for a spatial anchor, detailedly exploring the furniture in the Reading Room and a covert tickling of the Noguchi fountain. I’d argue that if these literal “touchpoints” were formally afforded to all visitors, all visitors’ experiences would be enhanced, not just experiences of the blind and partially sighted.

– Quietness of the gallery was on our side. The gallery was small, only had a few people in it, and was carpeted. Dave and Linda could hear each other without straining their voices or their ears. This made the experience very tranquil and pleasant. Imagine how different their visit would have felt in a noisier, more echoy gallery.

– We didn’t observe much active use of sound. L&D didn’t have audioguides, and there was no music or anything like that in the galleries. Linda mentioned various fountains in different museums that she liked. As a sighted person, I have to admit that fountains are not usually a highlight for me, but I think for Linda, because it’s something she can experience directly, they are often a highlight. What if museums with fountains (or any acoustically cool architectural feature) encouraged all visitors to close their eyes and really listen?

– We didn’t observe any use of tech. L&D kept this visit analog. Wonder how the visit might have been better/worse/the same with some type of technological aid? How to design such technology to support and enhance rather than distract and annoy?