We are fans of the Little Printer here in das labs, so when it was released last year and our Printers arrived, we started brainstorming ideas for a Cooper-Hewitt publication.

In a nutshell Little Printer is a cute little device that delivers a mini personalized newspaper to you every day. You choose which publications you want to receive, such as ‘Butterfly of the Day’ or ‘Birthday Reminders’. LP publications are created by everyone from the BBC to ARUP to individual illustrators and designers looking to share their content in a unique way.

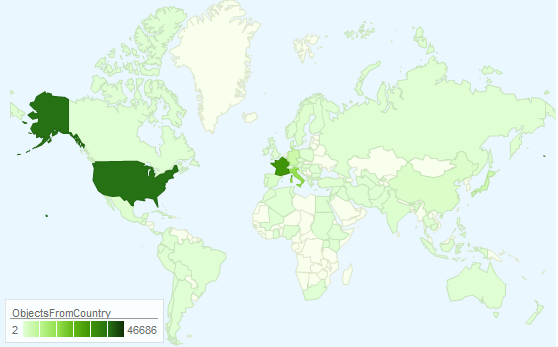

The first thing we thought of doing was a simple print spinoff of the existing and popular series on our blog called Object of the Day.

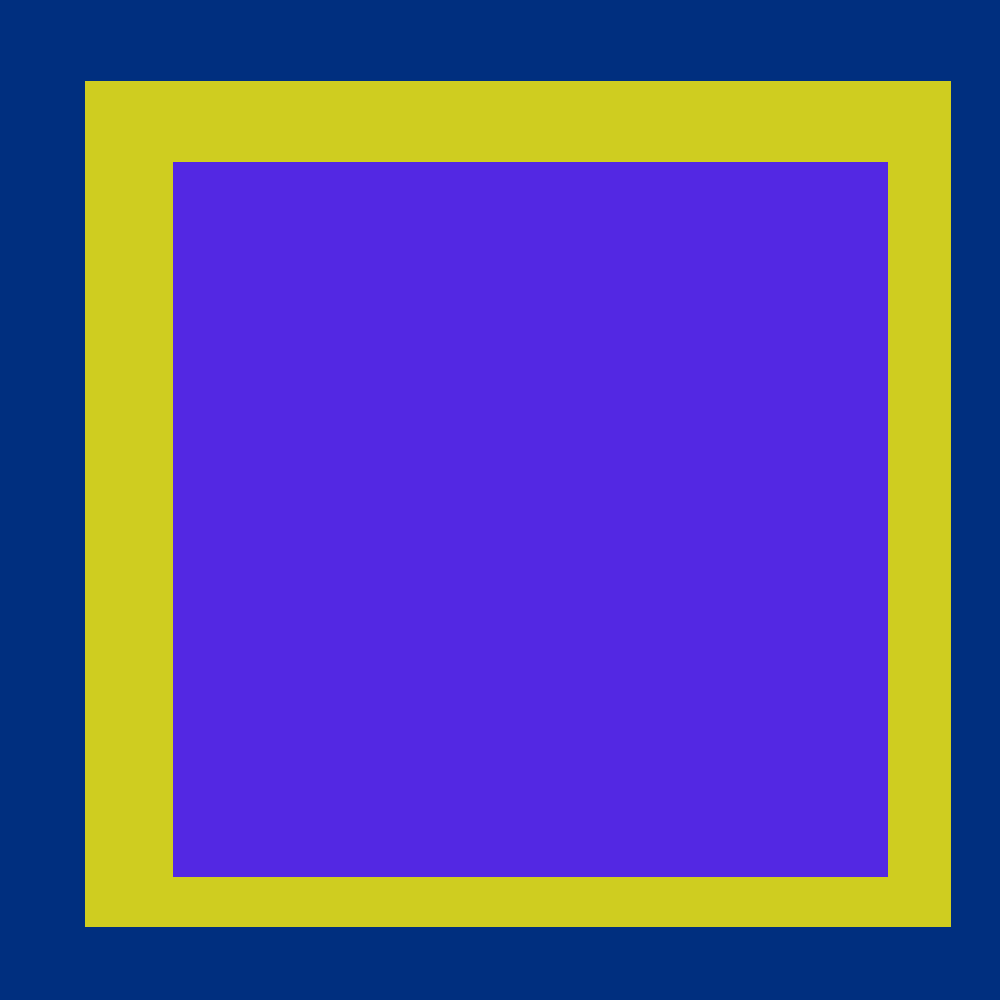

Aaron’s first stab at simply translating our existing Object of the Day blog series into (Little) print format.

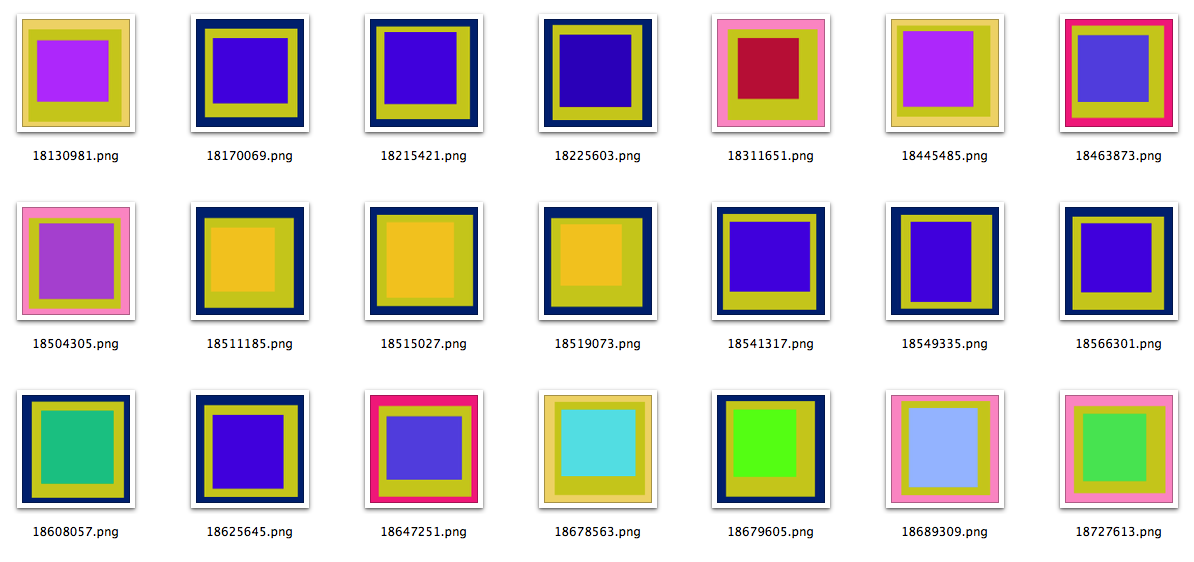

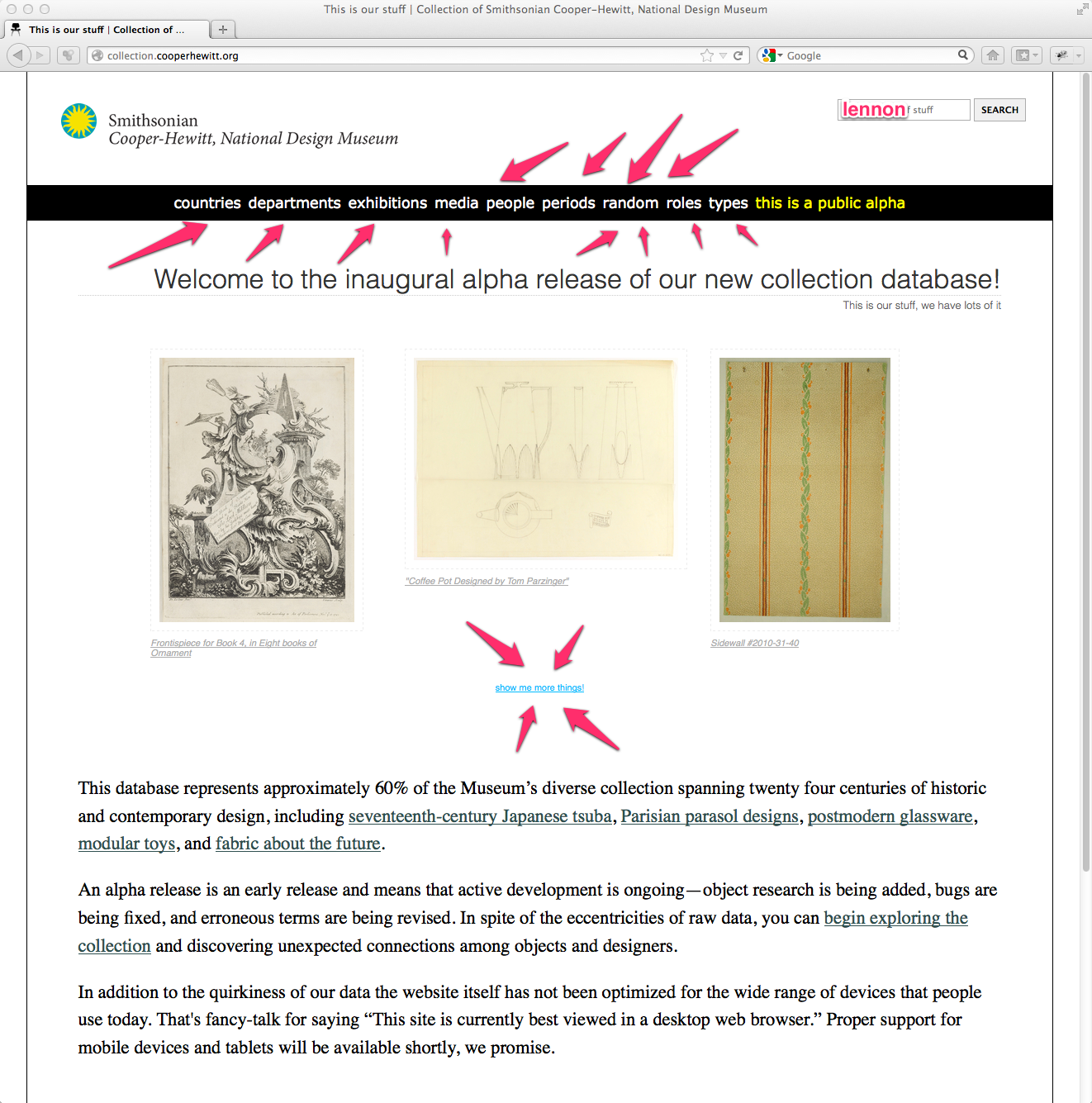

Then we tried a few more iterations that were more playful, taking advantage of Little Printer’s nichey-ness as a space for us to let our institutional hair down.

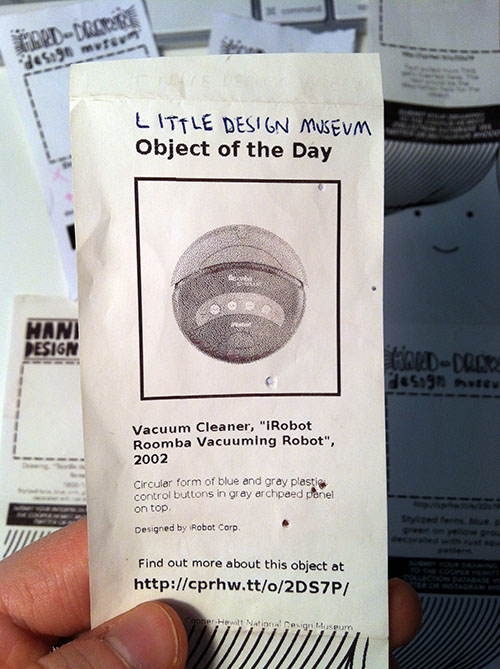

We tried to go full-blown with the decorative arts kitsch, but it came out kind of boring/didn’t really work.

Another interesting way to take it was making the publication a two-way communication as opposed to one-way, i.e., not just announcing the Object of the Day, but rather asking people to do something with the printout, like using it as a voting ballot or a coloring book. ((Rap Coloring Book is a publication that lets you color in a different rapper each week, I think it’s pretty popular. I was also thinking of the simple digital-to-analog-to-digital interaction behind Flickr’s famous “Our Tubes are Clogged” contest of 2006 which I read about in the book Designing for Emotion (great book, I highly recommend).))

Took a stab at a horizontal print format with a simple voting interaction. Why has nobody designed a horizontal Little Printer publication yet? Somebody should do that…

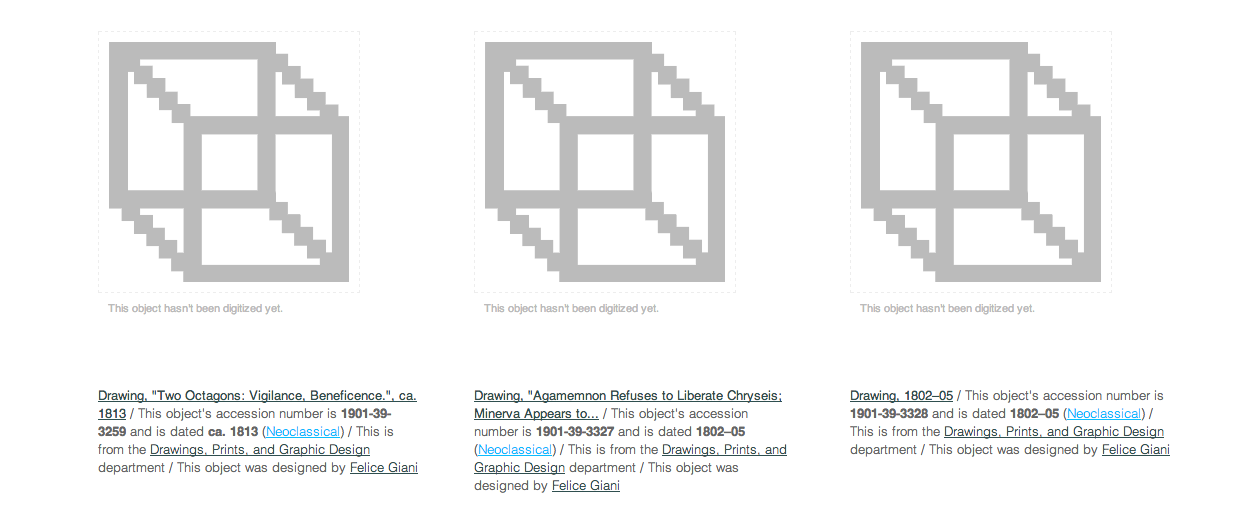

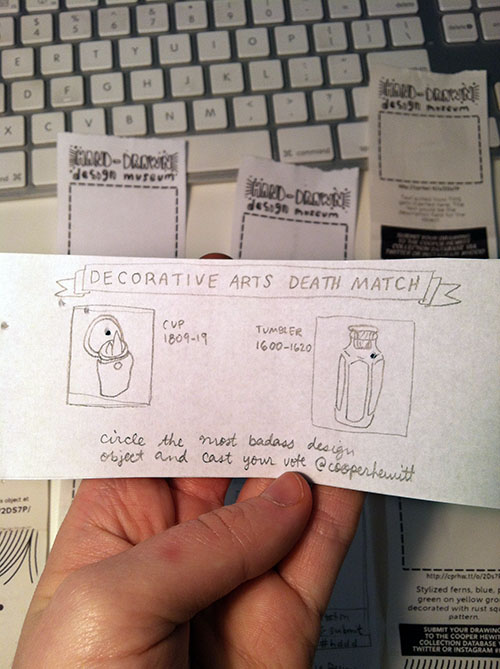

The idea everybody seemed to like most was asking people to draw their own versions of collection objects that currently have no image.

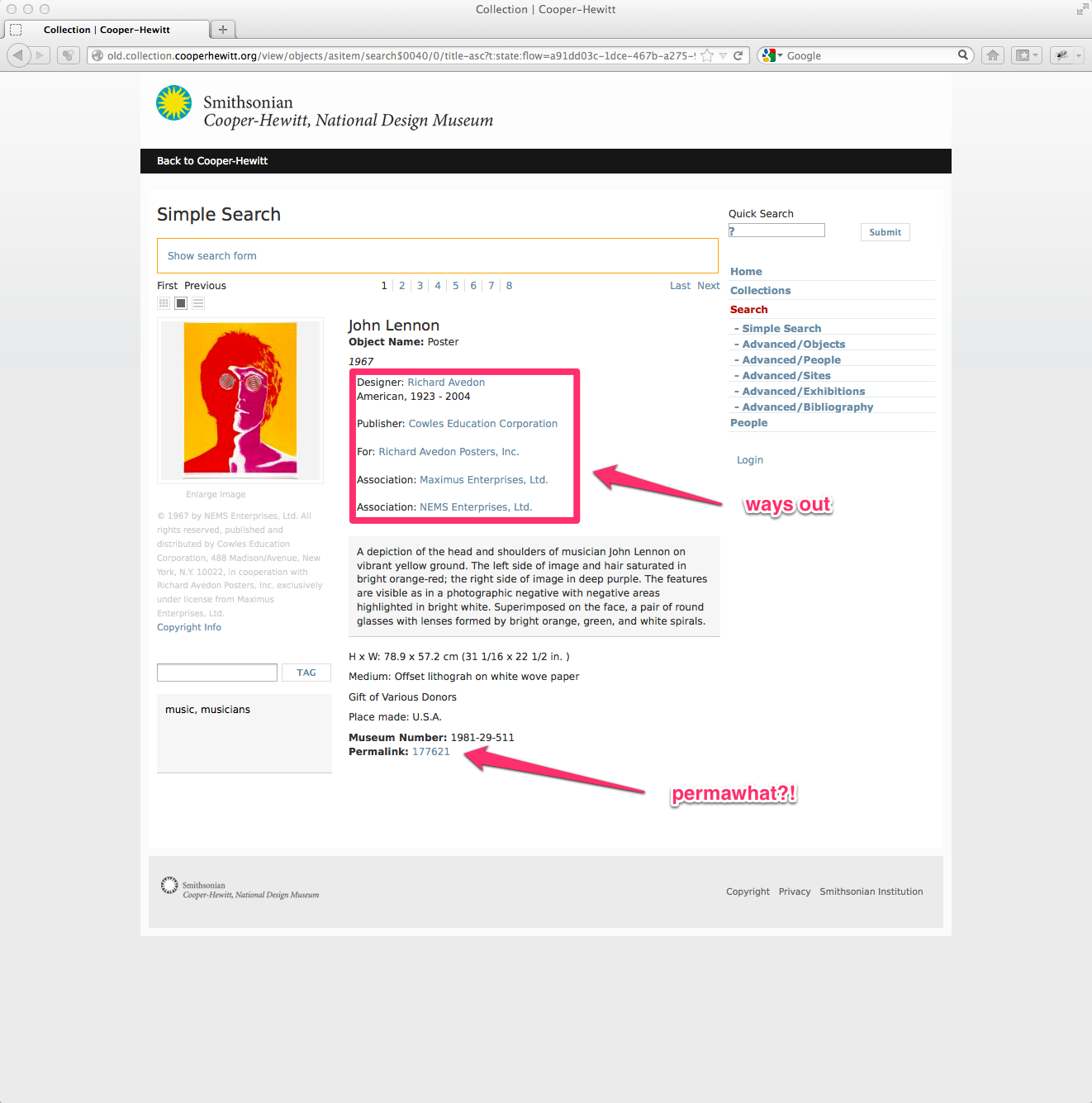

If you look on our Collections Online, you’ll see that there are plenty of things in the collection that “haven’t had their picture taken yet.”

I think this is a better interaction than simply voting for your favorite object because it actually generates something useful. Participants will help us give visual life to areas of our database that sorely need it. Similar to how the V&A is using crowdsourcing to crop 120,000 database images or how the Museum Victoria in Australia is generating alt-text for thousands of images with their “Describe Me” project. The Little Printer platform adds a layer of cute analog quirk to what many museums and libraries are already doing with crowdsourcing.

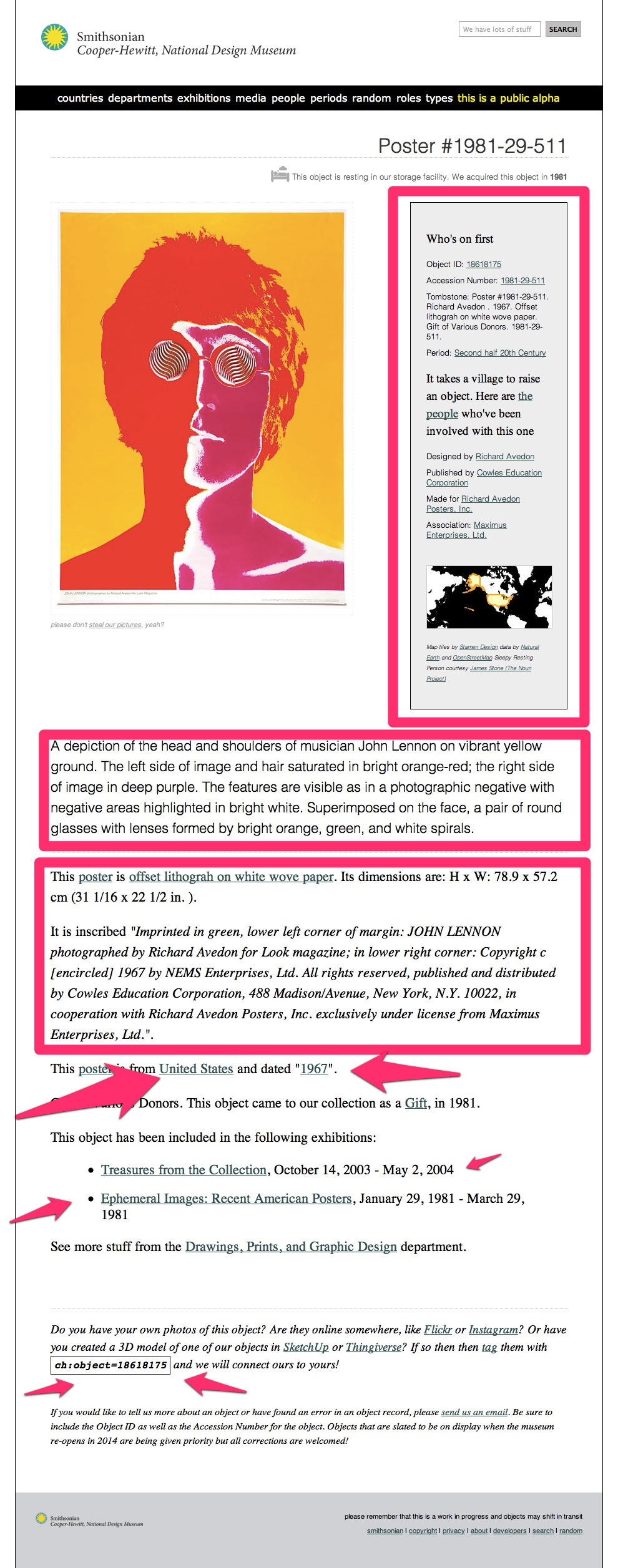

This prototype (now getting closer..) uses machine tags to allow people to link their drawings directly to our database. I printed this with an inkjet printer so it looks a little sharper than the Little Printer heat paper will look.

Lately at the museum we’ve been talking about Nina Simon’s “golden rule” of asking questions of museum visitors—that you should only ask if you actually CARE about the answer. This carries over to interaction design, you shouldn’t ask people for a gratuitous vote, doodle, pic, tweet, or whatever. I think some of the enjoyment that people will get out of subscribing to this publication and sending in their drawings will be the feeling that they’re helping the Museum in some way. [We know that there aren’t that many Little Printers circulating out there in the world but we do think that those early adopters who do have them will be entertained and perhaps, predisposed to playing with us.]

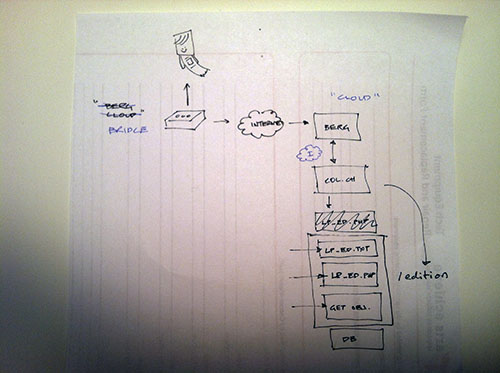

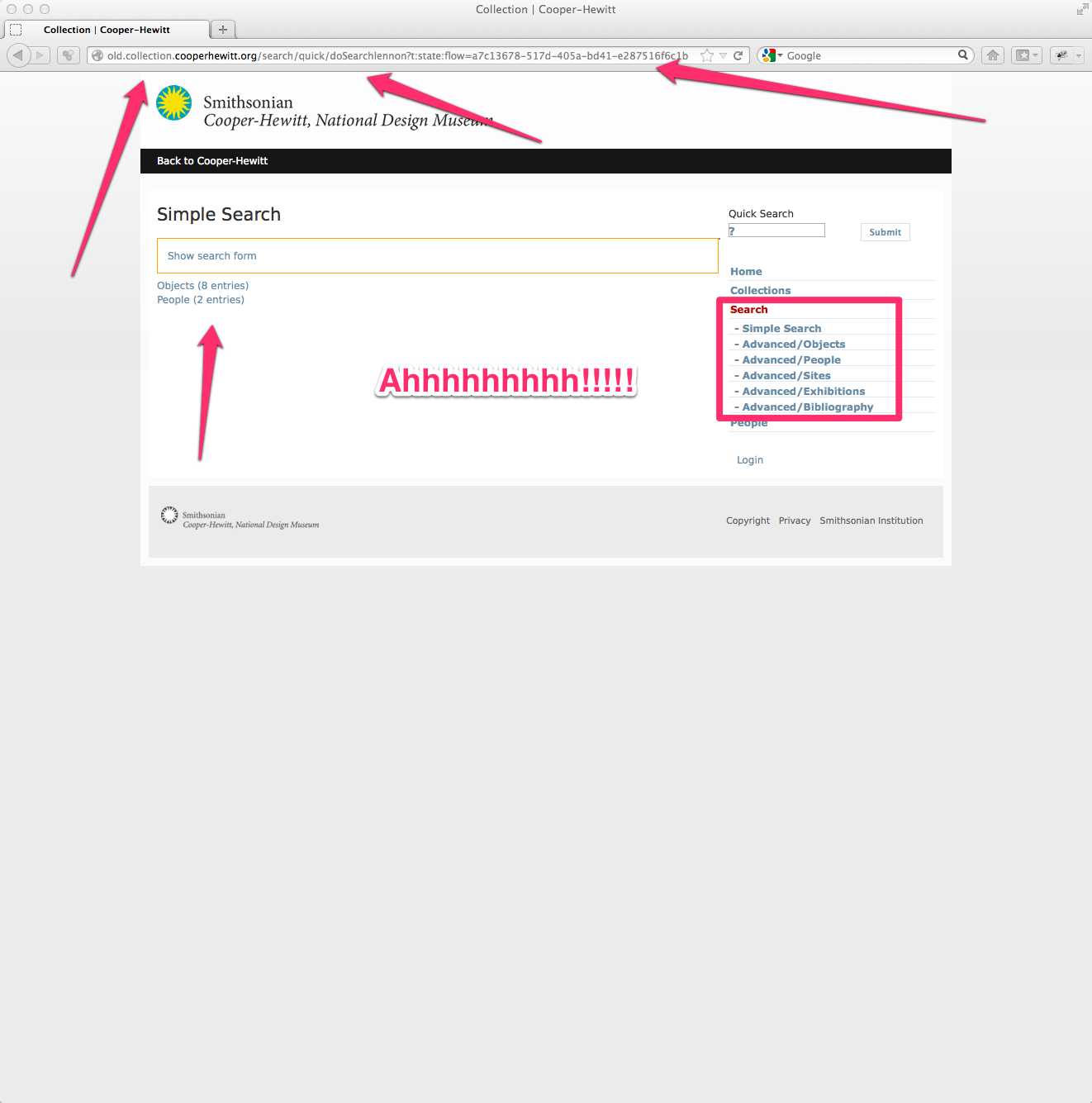

The edition runs as part of the collections website itself (aka “parallel-TMS“). We chose to do this instead of running it externally on its own and using the collection API because it’s “fewer moving parts to manage” (according to Aaron). Here’s a little picture that Aaron drew for me when he was explaining how & where the publication would run. If you’re interested in doing a standalone publication, though, there are several templates on GitHub you can use as a starting point.

We’ll see how people *actually* engage with the publication and iterate accordingly…