This is the second in a series of three “adventures in universal design,” a design research experiment carried out by Rachel Sakai and Katie Shelly. For an introduction to the project, see our earlier post, here.

COMPETITIVE PRODUCT SURVEY:

SCIENCE SENSE TOUR AT AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

AUGUST 15 2013

About once a month, AMNH offers a special tour for the blind, a program called Science Sense. Many museums in New York City have similar monthly tours for the blind. (The Jewish Museum’s Touch Tours, The Whitney Museum’s Touch Tours, MoMA’s Art inSight, the Met Museum’s Picture This! Workshop, and many more).

We chose to go on Science Sense because it worked with our schedule. Our tour was in the iconic Hall of North American Mammals.

Here are some highlights and observations from our tour:

– We gathered in the lobby of the planetarium. The tour’s organizer, Jess, explained that the tour meets in the planetarium entrance and not the main NMAH entrance because it is a more accessible entrance. (Ramp, no stairs, large doorways with push-button opening, etc)

– It was a summer Thursday at 2:30, so we were a small group. Many of our fellow tour-goers appeared to be about retirement-age, which makes sense given the time of day. There was one teenaged boy, who was with his mom who has partial vision.

– The group had a chatty and friendly vibe. About 10 guests total. People were chatting with each other and having getting-to-know-you type conversations during our walk to the Hall of Mammals.

– Only 2 out of the 10 attendees appeared to be blind or low-vision. Each of the blind/low-vision guests had a sighted companion with them. The other 6 attendees appeared to be fully sighted.

– Irene, our tour guide, wore a small amplifier around her waist and a head-mounted microphone (something like this). The hall wasn’t terribly loud, but the amplifier made for more comfortable listening (and probably more comfortable speaking, too).

– Once we arrived in the darkened Hall, Irene began our tour the same way most tours begin: an explanation of historical context. (When and why the dioramas were originally created, when and why they were restored… etc.)

– Irene described the first diorama thoroughly, element by element. (Backdrop, foreground elements, taxidermy animals.) One guest asked about how big the diorama is. Good question. Irene suggested that a second guide take the blind guests for a walk from one edge of the diorama to the other to get a sense of scale. This was a suggestion I wouldn’t have thought of; seems more fun than just stating a measurement.

– Irene had a number of touch samples on a rolling cart. Some plastic animal skulls and a sample swatch of bison fur. At the end of our time in front of the bison diorama, she gave everyone a chance to feel the musky, matted fur.

– Naturally, as Irene was explaining the diorama and the touch samples were sitting behind her on the cart, many other visitors to the Hall (not part of the tour) took the opportunity to touch the fun stuff as it sat unattended on the cart.

– We went around to four more stunning dioramas, where Irene and a second guide (who was in training) took turns describing and contextualizing the displays.

– I noticed that sometimes the sighted companion of one of the attendees would quietly add on his own description to what the tour guide was saying. Once I saw him lift his blind partner’s arm, and sweep it through the space to explain where different objects in the diorama were positioned. (We would later chat with these folks, Linda & Dave, who ended up going on a trip with us to the Met, which we’ll talk about in the next section.)

Takeaways:

– Rachel & I both happen to be big radio/podcast listeners. During the tour, I realized that a blind person’s experience is a lot like listening to radio. They are relying only on the guide’s words to “see” what’s there.

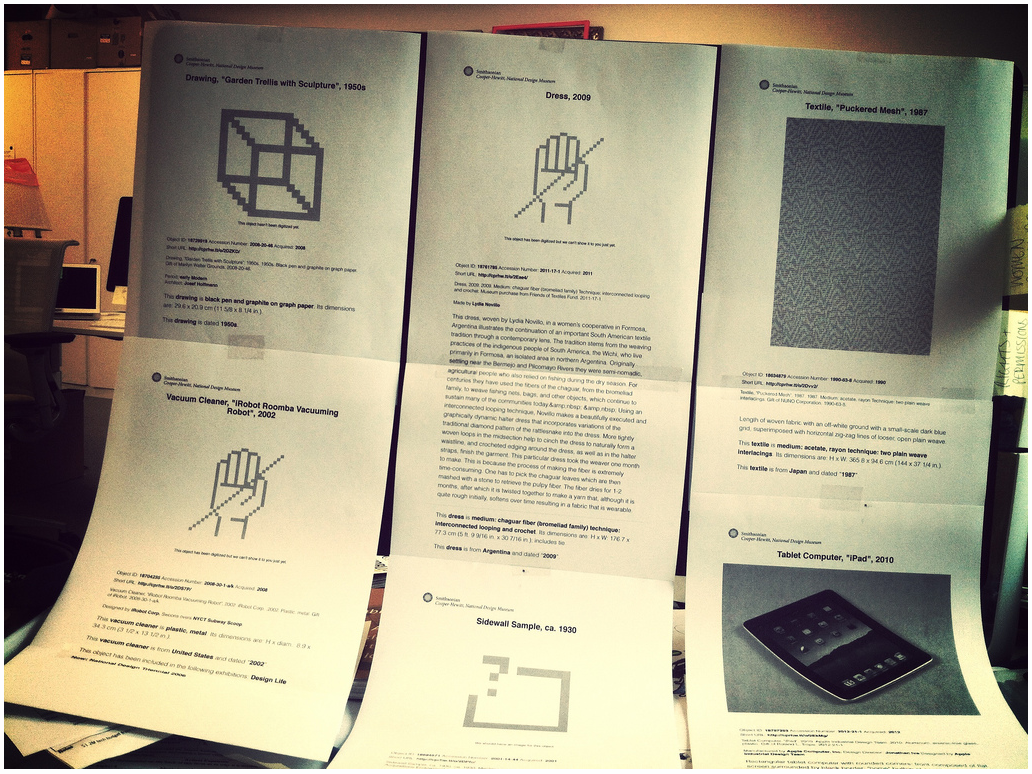

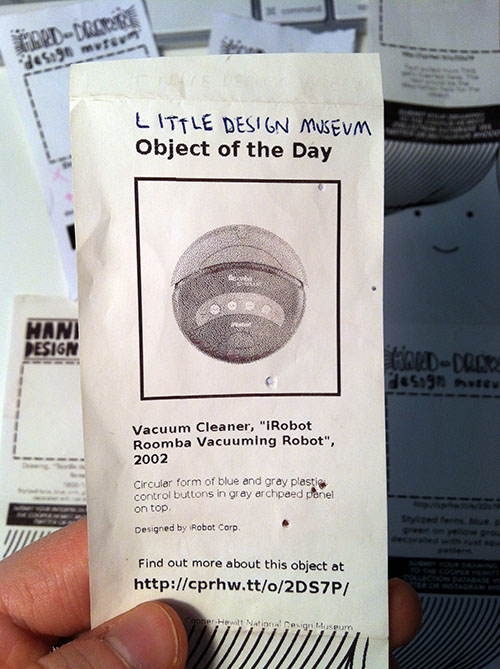

What if museum tour guides were trained to think and speak like radio hosts? What if each stop on the tour opened with a detailed, theatrically delivered, visual description? Listening to a luscious, mood-setting, masterfully crafted description of anything on display— be it a Bison diorama or a Dyson Vacuum Cleaner or a Van Gogh painting would be a delight for sighted and blind visitors alike.

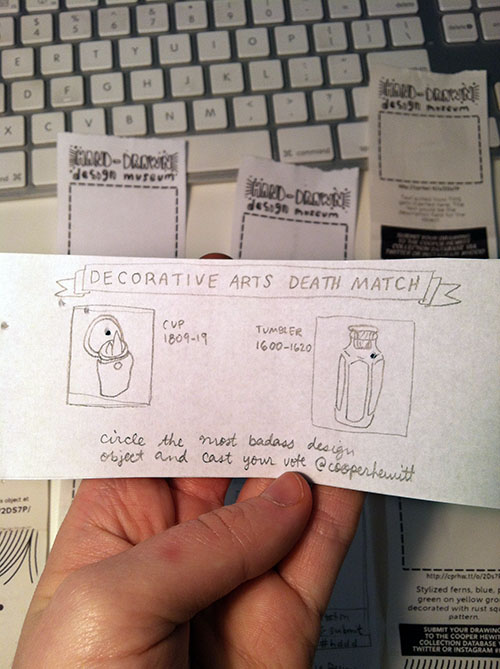

-There was some confusion about the basic size and shape of the dioramas. What if there was a tiny model of each diorama that visitors could feel? Blind visitors could understand scale and shape right away, and sighted visitors might enjoy a touchable model, too. Imagine touchable mini-models of paintings, sculptures, and other museum stuff, too.

Check out our third and last adventure in universal design research, observing a blind person’s museum visit.