Below are the slides and most of what I said at the 2014 Museums & The Web conference in Baltimore, Maryland.

“I believe that if we think first about people and then try, try, and try again to prototype our designs, we stand a good chance of creating innovative solutions that people will value and enjoy.” — Bill Moggridge

Let me begin by telling you a little story about a small museum that sat along 5th Ave. on New York’s Upper East Side. This is of course a largely fictional story. Names, and actual events have been changed.

This is the story of a little museum with big aspirations. Long ago this little museum had a website. It had a webmaster, and it published a blog. It even had a whole bunch of microsites, flash driven exhibition sites, event calendars and archives. In fact, it won a few Webby’s.

The website was very much the product of an organization trying to get the job done. And, it succeeded in this effort. Staff members would produce content on their company issued PCs and would then hand these documents off to the museum’s webmaster who would convert them into HTML and Javascript. The webmaster would press a specially designed “button” which would upload the new content to the little museum’s web servers where the pages would be served and maintained by a giant umbrella organization that had close ties to the government.

With a single webmaster managing the entirety of the museum’s web properties, the little staff of this museum faced an inevitability. It was just too much work for the webmaster to do alone. Even if they allowed the webmaster an apprentice, the workload would continue to grow, and the little museum’s website would suffer. Eventually, they all realized they would have to move towards a system that would allow the entire staff to collaborate more efficiently.

Eventually, they realized they would need a content management system.

There were many options out there already, and the little museum’s webmaster took stock in as many of them as he could. Meetings were had, and budgets were considered. The “committee to select a content management system” was formed, and consultants were brought in.

Wire frames were presented, and scopes of work were proposed, but the committee remained vigilant and put off making a decision as long as it could. They simply never felt like they had the right solution placed in front of them.

There was a lot at stake and many facets and bullet points drove them to a moment of indecision. There was due-dilligence due to their “mothership” in Washington, and there were “rights in data” clauses to be haggled over, with threats of time in a Federal prison always on everyone’s minds. Eventually the committee was disbanded and the project was put on hold.

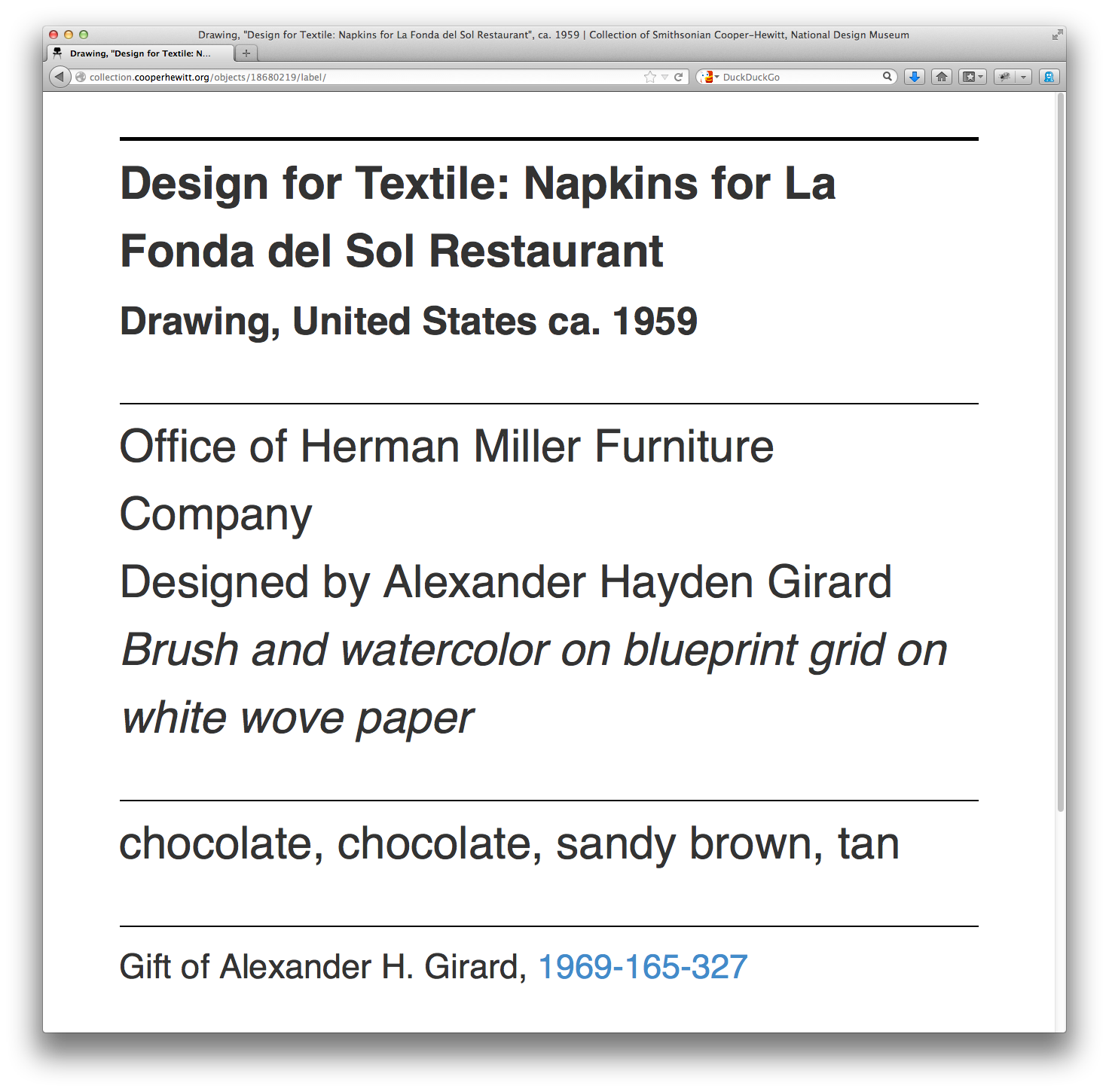

Time went on and the little museum’s website continued to shine as the public face of the institution. It continued to be updated with more and more content, and eventually the little museum even invested a fair amount of money in putting their collections online for all to see.

The word on the street was that this little museum’s website was starting to blow up, more and more people were beginning to rely on it as source of good information, and the time had come to re-think the idea of re-building.

The webmaster at the little museum was doing his best, running around from staff member to staff member, trying to understand what had been going on all this time. One day he had the fortune to sit in on a meeting with a prominent weblogger and asked him a very important question.

“What CMS do you think we should chose” the webmaster said.

“CMS’s are all basically the same”, said the blogger, “just chose one you like and don’t look back.”

The webmaster took this to heart and selected three CMS systems that were free and easy to set up. He presented these to the higher ups and after a couple of hours of debate and one technical review board meeting, the webmaster had his answer.

Drupal would be the content management system for the little museum. Drupal.

The end, well sorta.

Most of that actually happened at the Cooper-Hewitt. The team eventually just had to pick a system, (without a whole lot of experience with the product itself) and kind of just “go for it.” From that point on, the staff at Cooper-Hewitt were living with Drupal. Drupal, a word almost none of the staff had ever heard before became, in less than a few months, a dirty word, spoken in fits of anger and dismay.

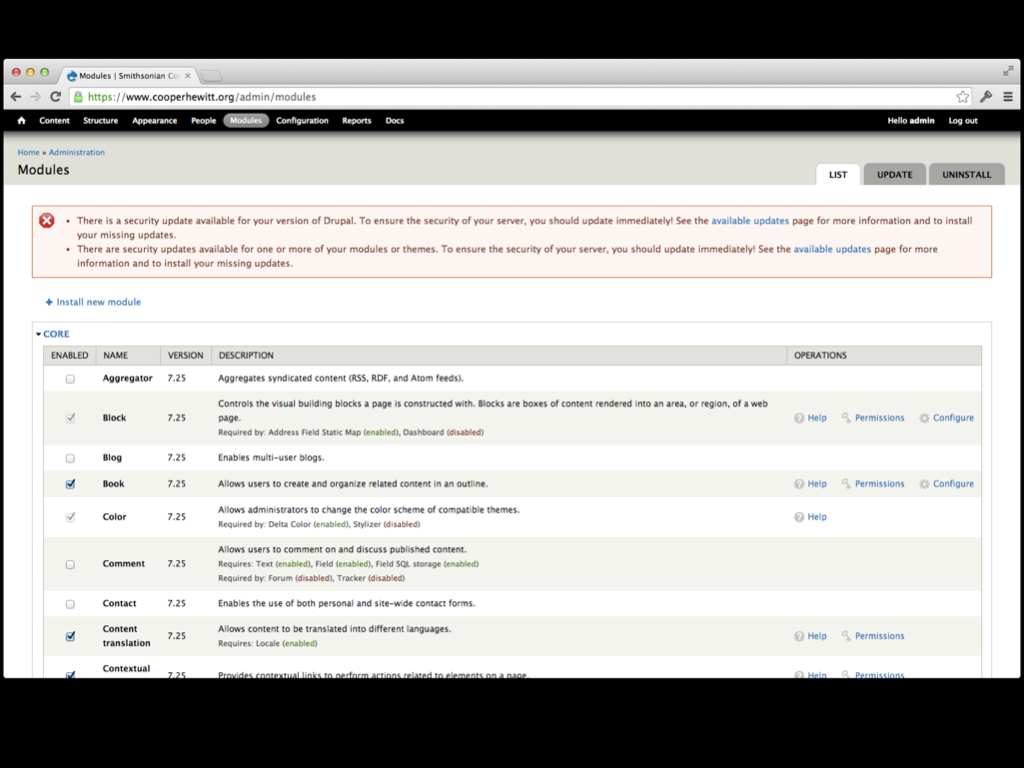

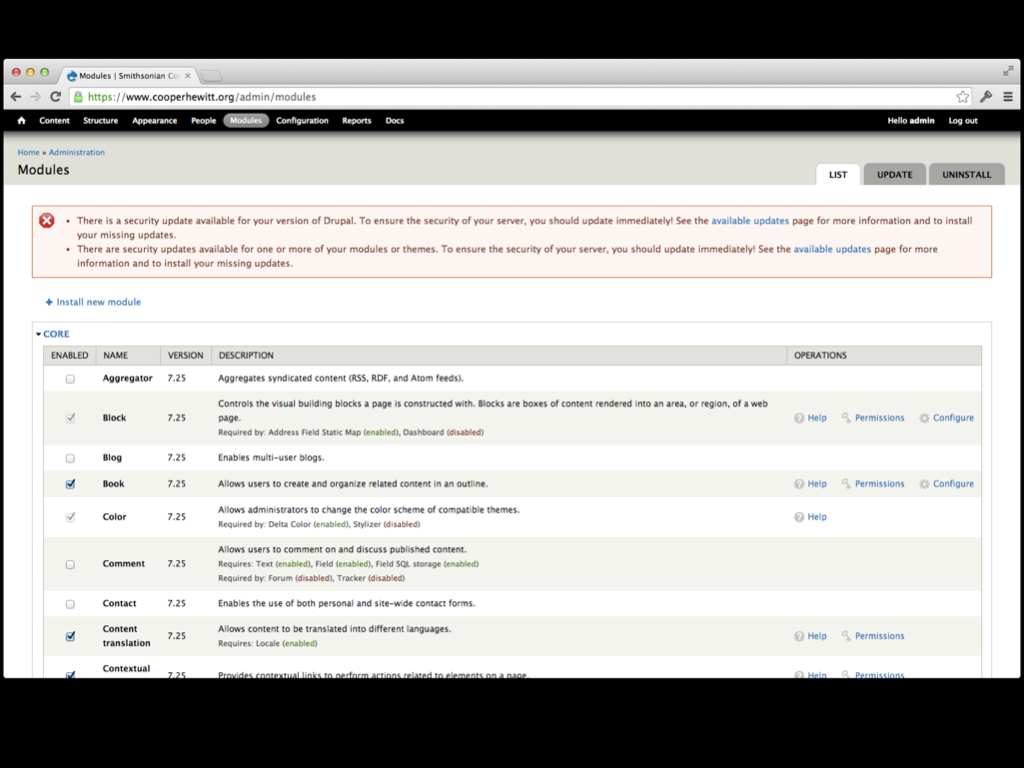

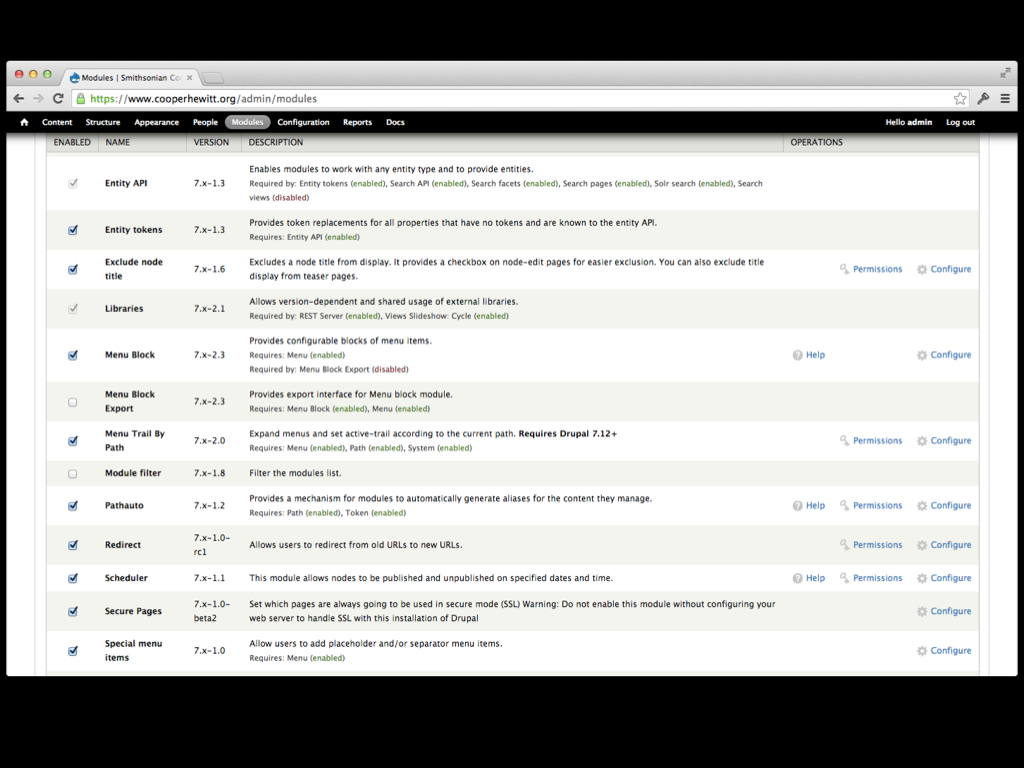

Now, before we go any further, it really needs to be said out loud that Drupal is really fine piece of software that has grown and evolved into a very sophisticated and well thought out framework for building websites. It has a rich community of developers and enthusiasts behind it and it powers some of the most popular websites on the planet. It’s used by giant companies far and wide, governments, and educational institutions all over. As well, our team in Washington has come a really long way in learning how to host and maintain Drupal based websites and presently, many of the latest Smithsonian websites are being built on Drupal. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with Drupal, we just realized, after a long time, it wasn’t for us.

I’m Micah Walter. I’m part of the nerd crew at Cooper-Hewitt. We are part of the Smithsonian ( that umbrella corporation in Washington )… and we are in the middle of a re-launch of our physical museum, as well as our digital presence.

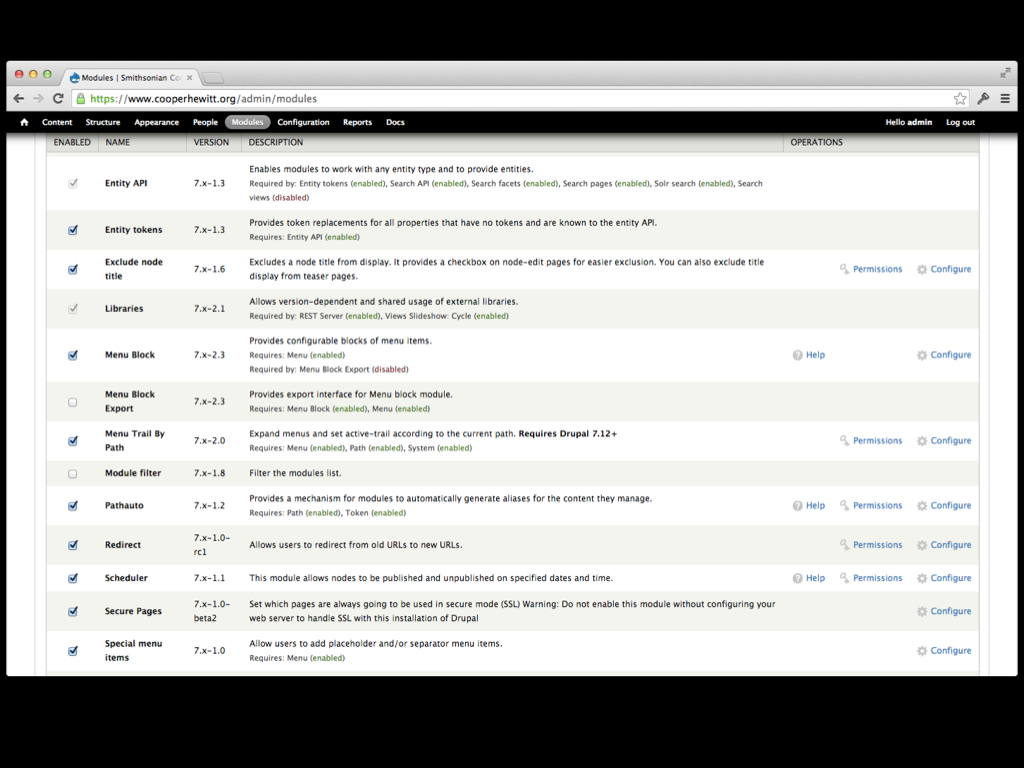

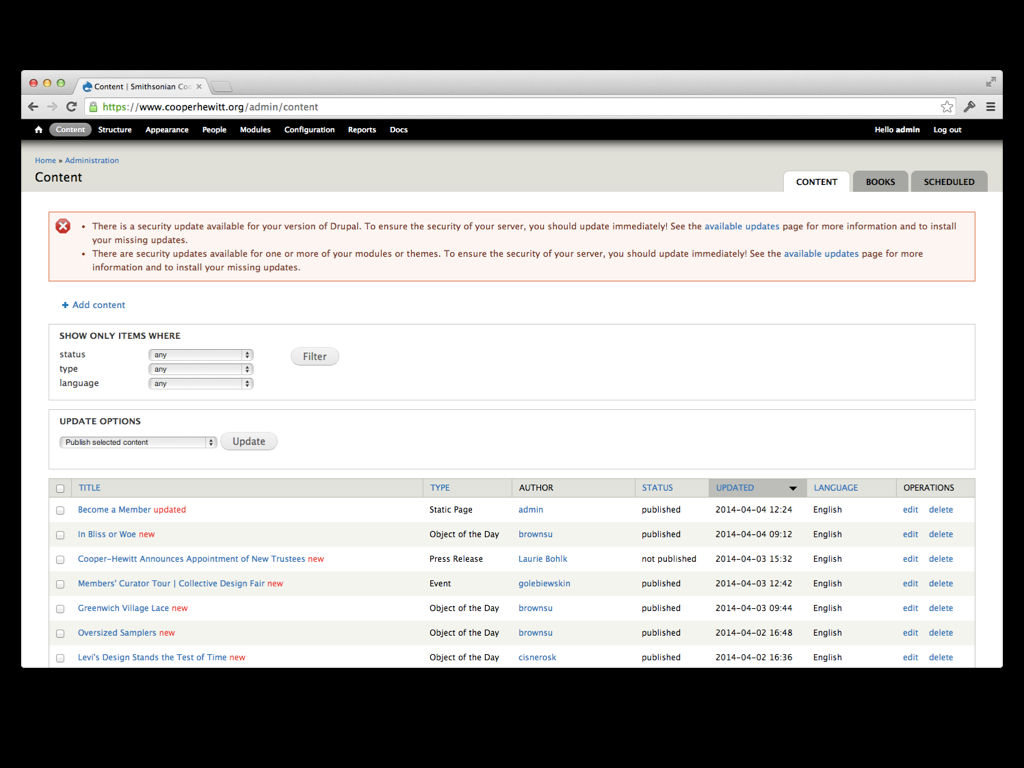

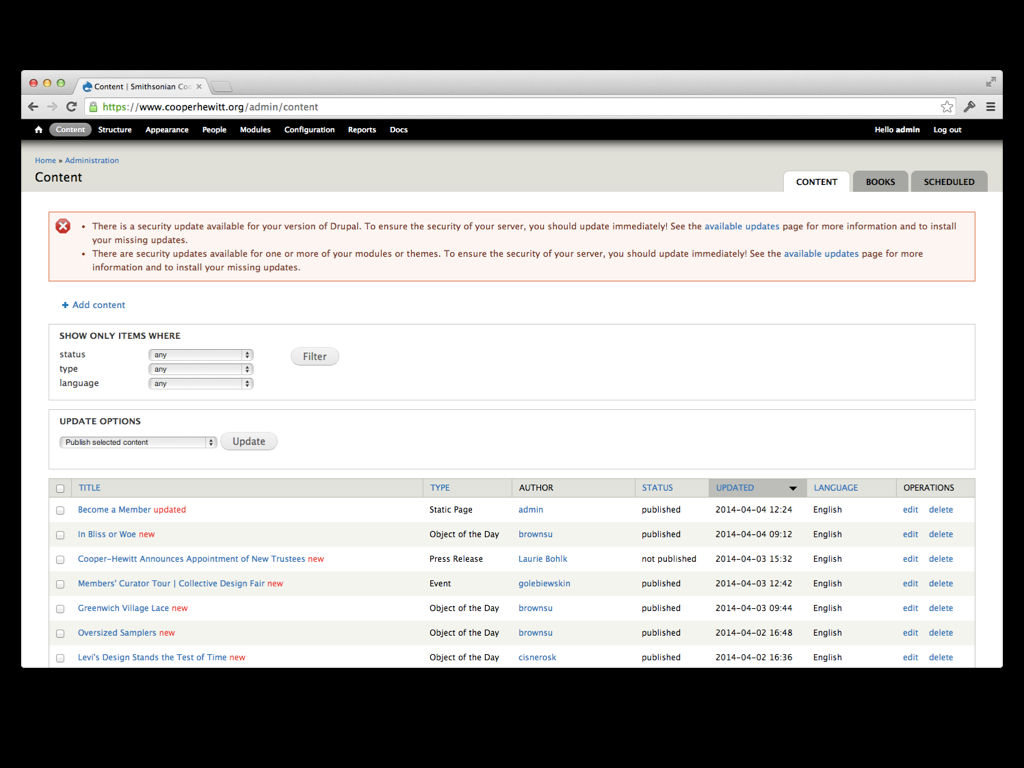

Cooper-Hewitt started it’s life with a CMS by installing a copy of Drupal 6. Shortly thereafter, we installed some modules, and more modules, and more…modules. Eventually we had a pretty awesome website. We hired an engineering team to convert the look and feel of the old website into a Drupal theme, and we “went live.” Cooper-Hewitt was on a CMS and it felt good.

random extra slide

Some time during this process we sat down with all the staff members to show off our new CMS. We took them on a tour of the system and poked around with a few of the CMSs features, with the hopes of getting staffers excited about the whole thing. The staff seemed to respond positively, and after a couple of months of configuring Drupal’s permissions matrix, we gave out login details to a select number of “power users” around the museum. A few of these power users got it right away and were off and running, updating their existing webpages when they needed to. It wasn’t too bad actually. Staff could easily log in, search around for the relevant content and make minor changes to their pages. The problems started to appear when they wanted to do just slightly more. A staffer wasn’t able to easily upload an image to Drupal. The image had to first be sent to our graphics person who would convert it to a jpeg, resize it for the web and then it would be sent to the webmaster who would upload it to an Amazon S3 server. Once this was done the webmaster would email the URL to the image back to the staffer who would then try and figure out how to insert it into their page.

Another issue arose when staffers tried to author new pages. It was simply difficult for them to understand how the new page would find its way within the information architecture that was already in place. How were they to set the new page’s URL and menu items. Those kinds of tasks inevitably wound up back on the webmaster’s desk.

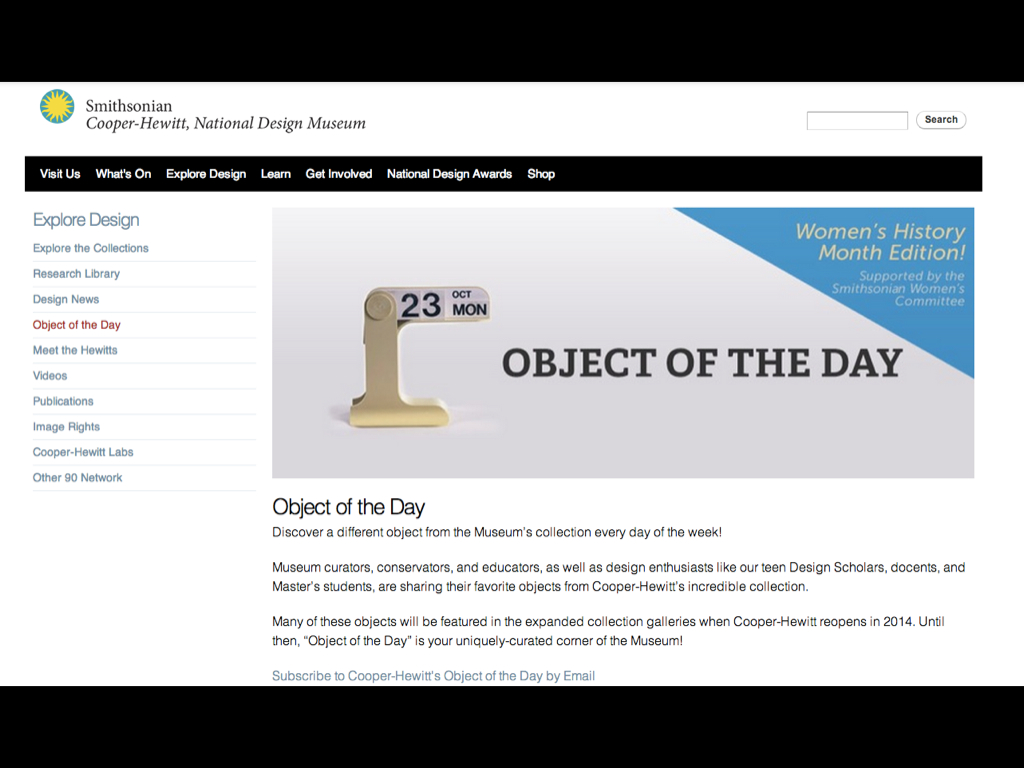

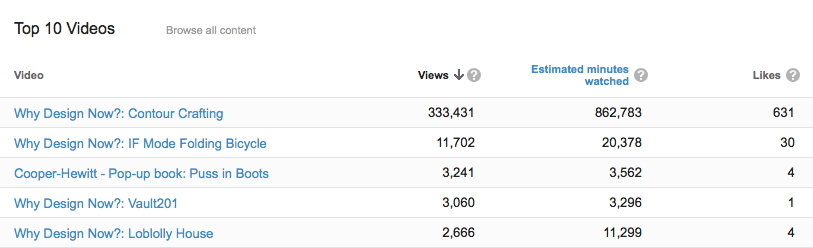

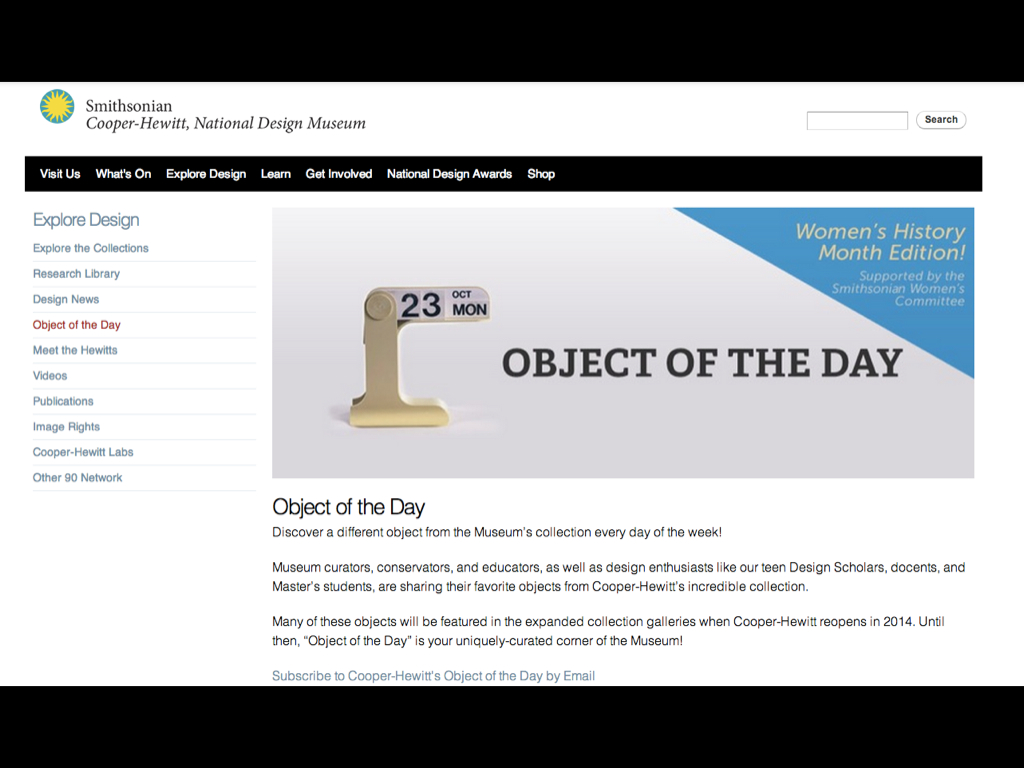

For the most part, notwithstanding a few hiccups here and there, Drupal 6 ran pretty smoothly. Staffers were able to distribute the workload a little more than they used to, and that was considered a good thing. But, about a year into it, a grant became available and the notion of running a daily blog about our objects turned into a reality. Object of the Day was born, and we had our work cut out for us.

Object of the Day went through many stages of evolution, eventually winding up as an institutional blog authored by staffers, students in our Masters program, docents, and even teens and high school kids interested in design. Every day another object from the collection was chosen and a post was written about it and published to our blog. Great pains were taken to ensure we considered the collection record, tags, the authors vitals and more. We met in committee meetings over and over and eventually worked out a plan to allow us to manage project. The end result would be a new post about a different object, every day.

In the beginning we toyed around with the idea of Object of the Day being run on a separate platform. We considered Tumblr, WordPress.com and even Blogger. But in the end, we decided we would put our new CMS to the test and put ourselves through the process of managing a daily blog with Drupal.

To accomplish this, the digital team realized we’d probably be wise to migrate to Drupal 7 in order to take advantage of its much improved back end user interface. So, with Object of the Day as catalyst, we moved ahead with plans to migrate our Drupal installation to D7. Consultants were hired, interns were enslaved and the whole process took just a few months. In the end we wound up with a fresh installation of Drupal 7, and about 20 or so contributed modules.

In parallel to this migration project we began to meet with staff members and work out the details of how this Object of the Day project would go down. We discussed a variety of organizational schemes, we talked about available resources, and how far the grant money might take us. In the end we came up with a pretty simple plan. Each month, one staff member would be the “editor” for Object of the Day. He or She would be responsible for collecting all the entries for the month, making sure they were entered into Drupal, edited and fact checked. They would then get scheduled to be published automatically on their specific day. This included many spreadsheets, checklists and meetings. It was of course, great user research for me and my team.

Once we had D7 up and running staff members started to get the hang of it. They started logging in and authoring content. And then the problems started to happen.

We already had about 1500 pages ( Drupal calls these nodes ) in the CMS. They were mostly static web pages about one program or another, or blog posts from the old days, or exhibition archives and other kinds of historic content. This was just fine as that content rarely got touched or updated. It was also fine when we wanted to add a fresh blog post or a new static page every once in a while…

The problem though was what happened when the monthly Object of the Day editor had to log in to start work on their thirty some posts for the upcoming month. It was nearly impossible for them to collect all the posts in one place within the CMS so that they could see what had been entered, what was finalized and what was ultimately scheduled. This was a major first hiccup and the digital team worked out a solution involving a number of custom Drupal views that would allow the editors to more easily see what they were working on. It kind of worked, but we could tell that it was a hack solution to a real problem.

The end result was, they lived with it. They lived with the system, learned to hate it, and just didn’t talk about it much. Drupal became this beast that they just came to terms with.

Time went one, and we all learned to work with Drupal. Many of the staff members became proficient enough to get by, and the calls to the webmaster desk lessened. But, the problems hadn’t gone away. In fact our little experiment to try and get staff members excited about authoring content on the web had actually backfired. Now, staff members authored content for Object of the Day because it was part of their job, listed in their work plans and reviewed during their performance evaluations at the end of each year. They hated it.

Meanwhile, Object of the Day took off. The public facing version of the blog became a big success. It received additional funding for a second year with the idea around the Sr. Management table being that it would go on forever. It was for a time our most popular page on the site.

If there is one truth we have learned about maintaining a website using a CMS its that you’ll eventually jump ship and switch to something else. In fact you may do this operation again and again. Its just the nature of the beast—the grass is always greener.

When we realized we needed to jump ship, we took to heart all the feedback we got from our content creators. We realized that what they really wanted were pleasant, easy to work with tools that allowed them to feel empowered. Tools that gave them a sense of authority, and made them feel good about the work they were doing. Like it was a way for them to communicate with the world all the important things they had going on.

In the end we chose WordPress. We looked at lots of options. We thought about even simpler options like a static site generator, or hmm, Squarespace? Could a museum run their entire website on Tumblr? All of these options afforded us with a great user experience, but seemed to trade of the ability to be flexible enough for our institutions needs. It really depends on the needs of each institution.

We searched far and wide. But we kept coming back to WordPress. It was familiar to everyone. Many of the staff already had their own WordPress blogs. WordPress gave us a nice balance between having the ability to create a sophisticated website and also being simple enough to use. In fact, while I was writing tools to migrate our content to WordPress, we realized that its more simplified system allowed us to re-organize our content, making the site easier to navigate. It’s not that we couldn’t do this in Drupal, but over time, Drupal just got out of control, because it let us.

We realized through the Object of the Day project that it was our CMS that stood in the way of success. The content was already good, the audience was already there. We just needed a way to get our own staff excited about doing it. It shouldn’t be hard. It should be really easy and really fun to do. WordPress lets our staff get excited about the work they are doing. It gives them a simple to use, enjoyable writing experience, and for the editors, we found some really great plugins that let them manage all the content without feeling overwhelmed. Thats really why we chose WordPress.

We kind of think of it as a downgrade on the technical side of things, but its definitely an upgrade when it comes to usability.

The end.

Postscript

There was some good discussion following the talk. A few things of note that were brought up included how our staff already had some experience with WordPress via our DesignOther90.org website, our use of EditFlow for notifications and calendaring/scheduling of content and Pressbooks to aid with the production of our eBooks.

We also talked a little about hindsight…