Ever since the online collection first properly went live in 2012 our collection images had a little line under them that said “please don’t steal our images, yeah?”. Whilst it was often commented that this was a friendly, casual approach that felt in keeping with the prevailing winds of the Internet, the statement was purposely vague and, at the end of the day, pretty unhelpful.

![]()

After all, “what is ‘stealing’ an image”? “Isn’t the Smithsonian, as a public institution, already owned by the ‘public'”? “What about ‘fair use'”? And, as many pointed out, “why are you claiming some kind of rights over images of objects that are clearly date from before the 20th century?”. Some also spotted the clear disconnect between the ‘please don’t steal’ language and our other visible commitments to open licensing and open source.

First, a bit of history.

The majority of the Cooper Hewitt collection predates its acquisition by the Smithsonian. The collection was originally at Cooper Union until the museum there closed in 1963. It was officially acquired by the Smithsonian in 1968 and the Cooper Hewitt was opened in the Andrew Carnegie Mansion in 1976. The effect of this history is that much of the pre-1968 collection is unevenly documented and its provenance very much still under active research. Post-1976 it is possible to see, in the metadata, the different waves of museum management and collection documentation, as new objects were added to the collection and new collection policies became formalised. Being a ‘new museum’ in 1976 also meant that much of the focus was on exhibitions, not so much on the business of documenting collections. Add to this the rise of computer-based catalogues and you have a very ‘layered’ history.

Cooper Hewitt has not had the resources or staff to undertake the type of multi-year Copyright audits that museums like the V&A have done, and as a result, with provenance and documentation in many cases quite scant, the museum has had to make ‘best efforts’.

With the recent tweaks to the online collection, we have finally been able to make some clarifying changes.

Like all Smithsonian museums, all online content is subject to institution-wide ‘Terms of use‘. This governs the ‘permitted uses’ of anything on our websites, irrespective of underlying rights. These terms are not created at an individual museum level but are part of Smithsonian-wide policy. You can see that whilst these terms allow only ‘allows personal, educational, and other non-commercial uses’ they encourage the use of Fair Use under US Copyright law.

However, that said, we think it is important to be clear on what is definitely out of Copyright, and what may not be. And over time, as the collection gets better documented, more of the unknowns will become known.

So here’s what we have done – its not perfect – but at least its better than it was. And, to be perfectly honest, we’re only talking about the possible rights inherent in the underlying object in the image, as the digital image itself was created by the Smithsonian. Some of the types of object in our collection may not be eligible for Copyright protection in the first place.

For objects from our permanent collection –

1. acquired before 1923 then we say “This object has no known Copyright restrictions. You are welcome to use this image in compliance with our Terms of Use.” For example, this medal acquired in 1907.

2. acquired in or after 1923 but has a known creation date [‘end date’ in our collection database] that is before 1923, then we say “This object has no known Copyright restrictions. You are welcome to use this image in compliance with our Terms of Use.” This 1922 textile acquired in 2015 is a good example.

3. acquired in or after 1923 but without a known, documented, creation date [‘end date’ in our collection database], then we say “This object may be subject to Copyright or other restrictions. You are welcome to make fair use of this image under U.S. Copyright law and in compliance with our terms of use. Please note that you are responsible for determining whether your use is fair and for responding to any claims that may arise from your use.” For example this ‘early 20th century’ Indonesian textile.

This scenario is far too common and you will come across objects that clearly appear to be pre-20th century that have not been formally dated, as well as objects that say in their name or description that they are pre-20th century but have not been correctly entered into the database and don’t have their ‘end date’ field completed. An especially egregious example is this 18th century French textile that has incomplete cataloguing. In the collection database it has no ‘end date’ (it should have 1799 as an ‘end date’) and clearly should have no Copyright restrictions.

4. acquired in or after 1923 with a known creation date also in or after 1923 [‘end date’ in our collection database], then we say “This object may be subject to Copyright or other restrictions. You are welcome to make fair use of this image under U.S. Copyright law and in compliance with our terms of use. Please note that you are responsible for determining whether your use is fair and for responding to any claims that may arise from your use.” For example this 2010 wallpaper.

Many of the ‘utilitarian objects’ in our collection – clocks, tables, chairs, much of the product design collection – are legally untested in terms of whether Copyright applies, however in many of these cases other IP protection may apply.

As the US Copyright Office states,

“Copyright does not protect the mechanical or utilitarian aspects of such works of craftsmanship. It may, however, protect any pictorial, graphic, or sculptural authorship that can be identified separately from the utilitarian aspects of an object. Thus a useful article may have both copyrightable and uncopyrightable features. For example, a carving on the back of a chair or a floral relief design on silver flatware could be protected by copyright, but the design of the chair or flatware itself could not. Some designs of useful articles may qualify for protection under the federal patent law.” [source]

For objects on loan from other institutions, companies or individuals –

5. irrespective of its known age, we now say “This object may be subject to Copyright, loan conditions or other restrictions”.

—

As you can see we have had to make some very conservative decisions, largely as a result of the incompleteness of our data and museum records.

If you spot any of these (you could download the entire metadata from Github to programmatically do this), log them with their accession number in our Zendesk and they will be prioritised to be fixed.

Small steps.

—–

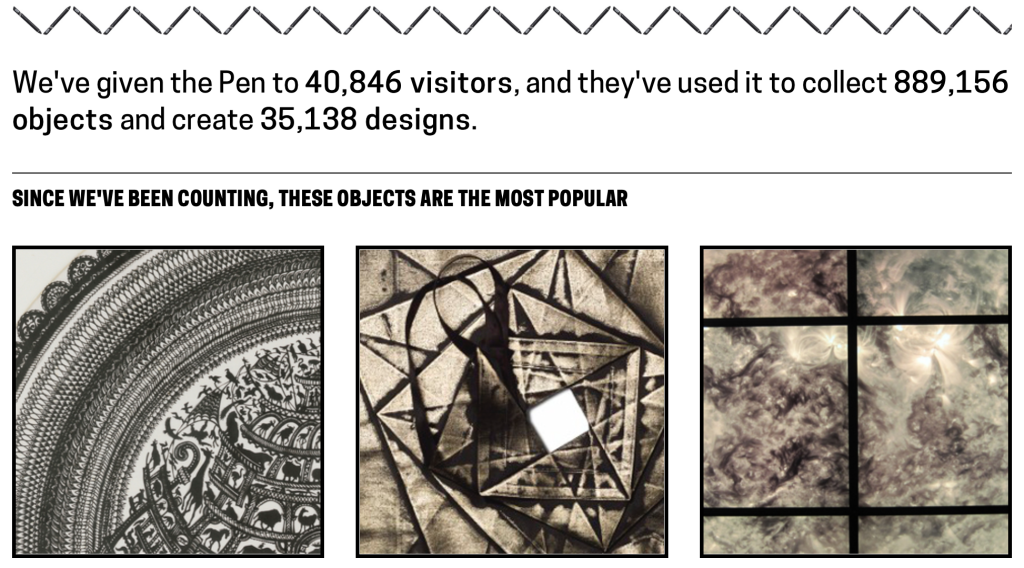

Update: Steven Lubar asked us on Twitter to share the number of object records that fall in to each of the categories. Here are those numbers:

| Acquired before 1923 | 32,442 |

| Acquired on or after 1923 and known creation date before 1923 | 5,232 |

| Acquired on or after 1923 and no known creation date | 136,372 |

| Acquired on or after 1923 and known creation date on or after 1923 | 30,357 |

| Loan objects | 13,477 |

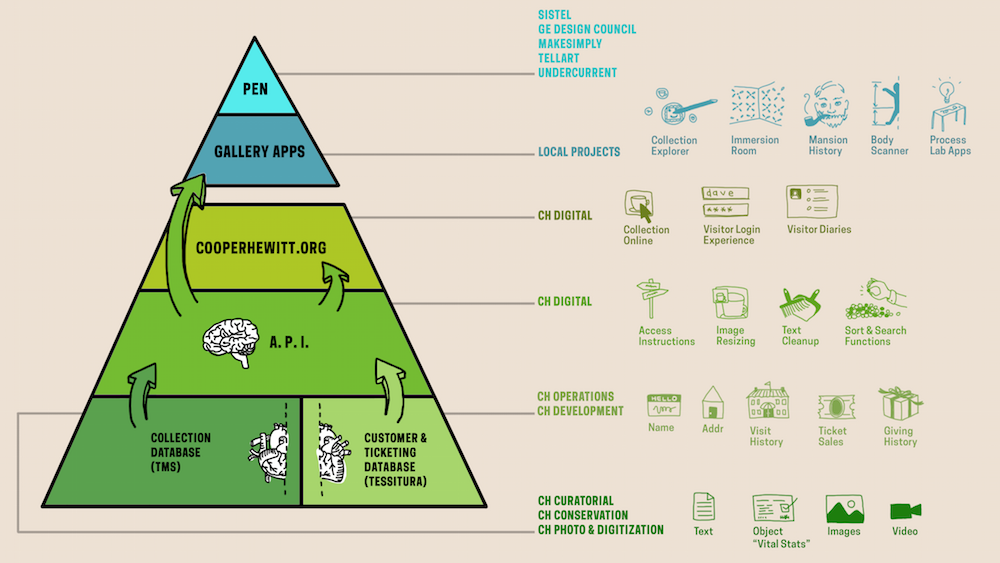

![Single visit 'lifecycle' of The Pen. Illustration by Katie Shelly, 2015. [click to enlarge]](https://www.cooperhewitt.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/04/PenCycle_v3-1024x663.png)