NEW YORK

the savage’s romance,

accreted where we need the space for commerce–

the center of the wholesale fur trade,

starred with tepees of ermine and peopled with foxes,

the long guard-hairs waving two inches beyond the body of the pelt;

the ground dotted with deer-skins–white with white spots,

“as satin needlework in a single color may carry a varied pattern,”

and wilting eagle’s-down compacted by the wind;

and picardels of beaver-skin; white ones alert with snow.

It is a far cry from the “queen full of jewels”

and the beau with the muff,

from the gilt coach shaped like a perfume-bottle,

to the conjunction of the Monongahela and the Allegheny,

and the scholastic philosophy of the wilderness.

It is not the dime-novel exterior,

Niagra Falls, the calico horses and the war-canoe;

it is not that “if the fur is not finer than such as one sees others wear,

one would rather be without it”–

that estimated in raw meat and berries, we could feed the universe;

it is not the atmosphere of ingenuity,

the otter, the beaver, the puma skins

without shooting-irons or dogs;

it is not the plunder,

but “accessibility to experience.”Marianne Moore, ‘New York’.

It has been said of New Zealanders that we are a poetry-loving nation, which is one of the reasons I’ve chosen a poem to start this blogpost on just a few of the experiences I’ve had during my time in the Digital & Emerging Media department (aka Labs) here at Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York City.

(The tenses change throughout as a reflection of how this #longread was assembled. They have been preserved to preserve the moments that they were written in).

I’m here on a three-week scholarship in memory of the late Paul Reynolds, a man who loved libraries, museums, art, archives and digital access to them. Like Bill Moggridge, the former director of the Cooper-Hewitt, Paul passed away of cancer before his time. Paul would have been so interested by what this museum is doing.

The award is administered by New Zealand’s library and information association, LIANZA, and I’ve also been generously supported by my workplace, the First World War Centenary Programme Office within the Ministry for Culture & Heritage, to take it up.

In particular, I’m here because I wanted to study a museum in the midst of transforming itself into an environment for active engagement with collection-based stories, knowledge, and information – or ‘experiential learning’ – and the innovative use of networked media in this context. It has been a rare privilege to be here while the Cooper-Hewitt are going through this change.

New York is no longer “starred with tepees of ermine and peopled with foxes” – it’s more kale salads and small dogs. Nonetheless, you can get a sense of some of the experiences I’ve had since being here on my #threesixfive project for this year.

The rules for this project are pretty simple. Each day, I take a photograph using my cell phone and Instagram and connect it with one from the past in the online collections of a library, archive or museum. Connections can be visual, geographical, conceptual, or tangentially semantic.

In New Zealand, I draw on historical images from the pictorial collections of the Alexander Turnbull Library, largely because they make their online items so easy to share and re-use. Here, I’m borrowing (with permission) material from the New York Public Library.

I sometimes refer to this as my ‘this is water’ project, in reference to David Foster Wallace’s commencement address to the graduates of Kenyon College in 2005. As Wallace describes ‘learning how to think’ in his post-modern way:

It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience.

I choose to pay attention to the present as well as the past presents within it. I think this is also a reasonably accurate description of the work the team behind the Cooper-Hewitt Labs, and those they work with in the wider museum, are doing as well.

*

I’ve had an eclectic curriculum while I’ve been here. If my learning journey were a mythic story, it would go a bit like this:

Act One:

– The ordinary world: I go about my daily life working for the government in New Zealand, but know that I am lacking in-depth knowledge of how to move from ‘publishing content’ to ‘designing experiences’ for learning.

– Call to adventure: I get an email from LIANZA telling me that I have won an award to gain this knowledge. (A major earthquake also strikes the city).

– Meeting with the mentor: Seb Chan begins preparing me from afar to face the unknown. Emails and instructions arrive. I find an apartment. I book tickets for planes and theatre shows.

– Crossing the threshold: I cross from the ordinary world into the special world. Seb invites me to Central Park (near the Cooper-Hewitt museum) with his family. I get instructions for catching the subway and learn where to get palatable coffee. I obtain a subway ticket – my talisman.

Act Two:

– Approach to the Inmost Cave: I re-enter the subway and enter the Cooper-Hewitt where the object of my quest (knowledge) exists. There are security guards and curators and educators. I meet the members of the Cooper-Hewitt labs team. There is a mash-up picture on the wall of a cat with a unicorn horn. Another shows a cat being . . . Wait, what’s happening in that image?

Things happen . . . I get a virus and lose my voice . . . and then here I am three weeks later preparing to return home to the ordinary world, bottling some of the elixir by way of this blog post.

I draw on the idea of mythic storytelling not to be clever (well, maybe a little bit), but also to introduce some of the values and influences shaping the Cooper-Hewitt’s approach to their museum redevelopment.

Seb has written great posts on the two experimental theatre pieces Then She Fell by Third Rails Projects and Sleep No More by Punchdrunk over on Fresh and New. Among other things, these hint at the Cooper-Hewitt’s choice to knowingly break the rules and tell stories in a non-linear way. I won’t cover the same ground here.

Another key inspiration is the Museum of New Art in Tasmania.

The idea of the talisman (in Then She Fell a set of keys; in Sleep No More a white mask; in MONA the ‘o’) is an important one and seems to inform the Cooper-Hewitt’s approach to visitor technology. Devices that are accessible to all, the visitor’s ability to unlock stories through interaction, and the availability of all the information about collection items being online after you visit are also relevant.

In addition to the ‘memorability’ of the event, a few other thoughts spring to mind on elements of Then She Fell and Sleep No More. Both relate to a conversation I had with Jake Barton of Local Projects on the relationship of audience to successful experience design. I’ll talk more about Local Projects later in this post.

Meanwhile, in both Sleep No More and Then She Fell, all you are given as you are guided to cross the threshold into the story-world are the rules for engagement and a talisman. Beyond this the ‘set’ (which incorporates the atmosphere and fabric of the site it is layered over) feels simultaneously theatrical (magical) and life-like (real).

I mention this because of the observation Jake made on creating digital applications that are wondrous enough to work for everyone because they tap into real-world human experiences. Obviously you wouldn’t take an eight year old to Sleep No More, so content choices are important. But the fundamental interaction works for everyone. This is also the case with the Cleveland Art Museum line and shape interactive.

In Then She Fell, these interactions are also personalised and, while guided, audience members make choices that drive the outcome of the scene. Taking dictation for the Mad Hatter using a fountain pen, for example, an actor improvised and remarked “my, you do have nice handwriting. I can see why you come highly recommended”. In another scene plucked from the database of scenes, a doctor asked me a series of questions as he progressively concocted a blend of tea for me, which I then drank. Other scenes were arrestingly intimate.

Another striking aspect of these environments is the radical trust the theatre company invests in its audience to be human and responsible. Of course none of the objects or archival files and letters in Sleep No More or Then She Fell are real, nor are the books copies of last resort.

But the fact that you can touch them and leaf through them and hold them in your hand, or that you can use them to figure things out is a really potent part of the experience.

*

Quote from Carl Malamud above Aaron Straup Cope’s desk.

My time in New York hasn’t all been theatre visits and blog publishing. With the Carnegie mansion that houses the Cooper-Hewitt closed for renovation and expansion of the public gallery space, I’ve also been spending time with staff immersed in the process of design and making.

When the building re-opens next year, the museum will be an environment that, as Jake Barton of Local Projects put it, “makes design something people can participate in” – not just look at or learn ‘about’ through didactic label text or the end-product of someone else’s creativity.

Local Projects are the media partners for the Cooper-Hewitt refurbishment, with architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Their philosophy is encapsulated in a quote from Confucius that Jake frequently references in his public talks;

I hear and I forget.

I see and I remember.

I do and I understand.

You can see how complementary this thinking is with the immersive theatre environments of Sleep No More and Then She Fell.

By way of illustration, the Cooper-Hewitt wants to encourage a more diverse range of visitors to learn about design by letting them collect and interact with networked collection objects and interpretive content in the galleries.

New Zealanders might think of the ‘lifelines’ table at the National Library of New Zealand designed by Clicksuite, which is driven off the Digital New Zealand API; and Americans might recall the recent collection wall at the Cleveland Art Museum, also designed by Local Projects.

But the Cooper-Hewitt is neither a library nor an art museum. It’s a design museum – “the only museum in the United States dedicated just to historic and contemporary design”.

Consequently, applications Local Projects develops with the museum also seek to incorporate design process layers where visitors can make connections and learn more about objects on display and also be designers.

The challenge, as Jake articulated it when we met, is ‘how you transmit knowledge within experiential learning (the elixir)?’. How do you make information seep in in a deeper way so that visitors or audience members do, in fact, learn?

The gradual reveal of the story in Then She Fell, with spaces also for solitary reflection and contemplation, is significant I think. I suspect I’m not the only one who googled the relationship of Alice Liddell to Lewis Carroll in the days after the performance.

*

If Then She Fell and Sleep No More were like slipping into a forgotten analogue world of the collection stores, Massive Attack v Adam Curtis was like all of the digitization projects of the past decade come back to haunt you.

Curtis describes this ‘total experience’ as a “a gilm’ – a new way of integrating a gig with a film that has a powerful overall narrative and emotional individual stories”. It’s not too far a cry from the word we use in New Zealand to describe the collecting sector of galleries, libraries archives and museums and their potential for digital convergence: a glam.

Imagine Jane Fonda jazzercising it up on a dozen or so massive screens on three walls of a venue, collaged with Adam Curtis’ commentary on how the 80s instituted a new regime of bodily management and control, and Massive Attack with Liz Fraser and Horace Andy covering 80s tunes that you can’t help moving along with. This is the first time I’ve experienced kinaesthetic-visual juxtaposition as a storytelling technique.

It is really hard to find yourself dancing to the aftermath of Chernobyl. It is also very memorable.

As Curtis describes the collaboration between United Visual Artists, Punchdrunk’s Felix Barrett and stage designer Es Devlin: “What links us is not just cutting stuff up – but an interest in trying to change the way people see power and politics in the modern world.”

“I see the people who created our Internet as a gift to the world” – Carl Malamud

“A fake, but enchanting world which we all live in today – but which has also become a new kind of prison that prevents us moving forward into the future” – Adam Curtis

How do we transform our institutions into way-finding devices for the cultural landscapes of the present and past presents, not prisons?

*

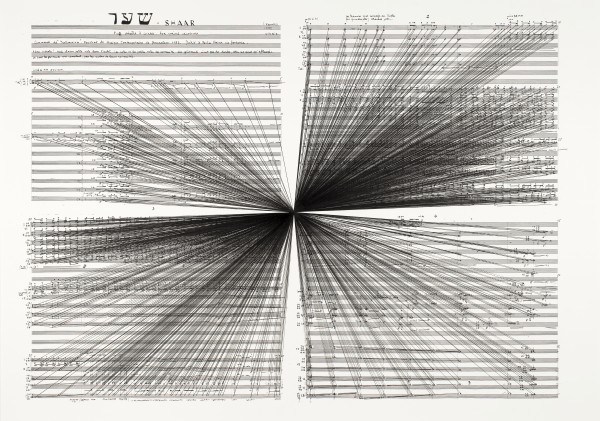

Marco Fusinato, ‘Mass Black Implosion (Shaar, Iannis Xenakis)’ 2012. (Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery)

“To make these drawings, Fusinato chose a single note as a focal point and then painstakingly connected it to every other note on the page” – MOMA interpretation label

Like many museums around the world, the Cooper-Hewitt as a Smithsonian-Institution has been seeking to broaden access to its collections online and deepen relationships with its audiences.

Much of the recent work of the museum that I’ve observed has focused on establishing two-way connections and associations between each of the many hundreds of objects that will physically be on display in the galleries and at least ten related ‘virtual’ objects and related media.

These thousands of digital objects in total will be available through the Cooper Hewitt’s collections API, which will also be a foundation for interactive experiences and other applications where people can manipulate and do things with content to learn more about design and the stories embedded in the museum’s collections.

But there’s a snag.

The vast majority of information and story potential, the knowledge and the ability to see meaningful and significant connections, isn’t in the database. It’s in the heads of the collection experts: the curators. Extracting this narrative and getting it into useful digital form is a huge undertaking.

Progress is being made though. I happily sat in on a checkpoint meeting for curators to make sure that objects they were tagging with a vocabulary (co-designed with the museum’s educators who bring “verbs to the curator’s nouns”) would not be orphaned. If objects are tagged, and another curator doesn’t use the same tag, the connection will be lost.

Thus, as one curator put out a call for colleagues to dive into their part of a collection, a wallpaper with a Z pattern found its match in a Zig Zag chair. Pleated paper found its match in an Issey Miyake dress. This is a laborious and time-consuming process, coordinated by Head of Cross-Platform Publishing Pam Horn.

But it means that the collection is starting to come alive in that ‘1 + 1 = 4’ way that is so magical. Through a balance of curatorial and automated processes, these connections and pathways through the collection will (all going to plan) continue to multiply over the months to come.

Visitors will also be able to find their own way through the knowledge the museum holds, and access all of the data online – much as every museum is also trying to connect pre- and post-visits together.

“Now find your own way home” – Massive Attack v Adam Curtis

*

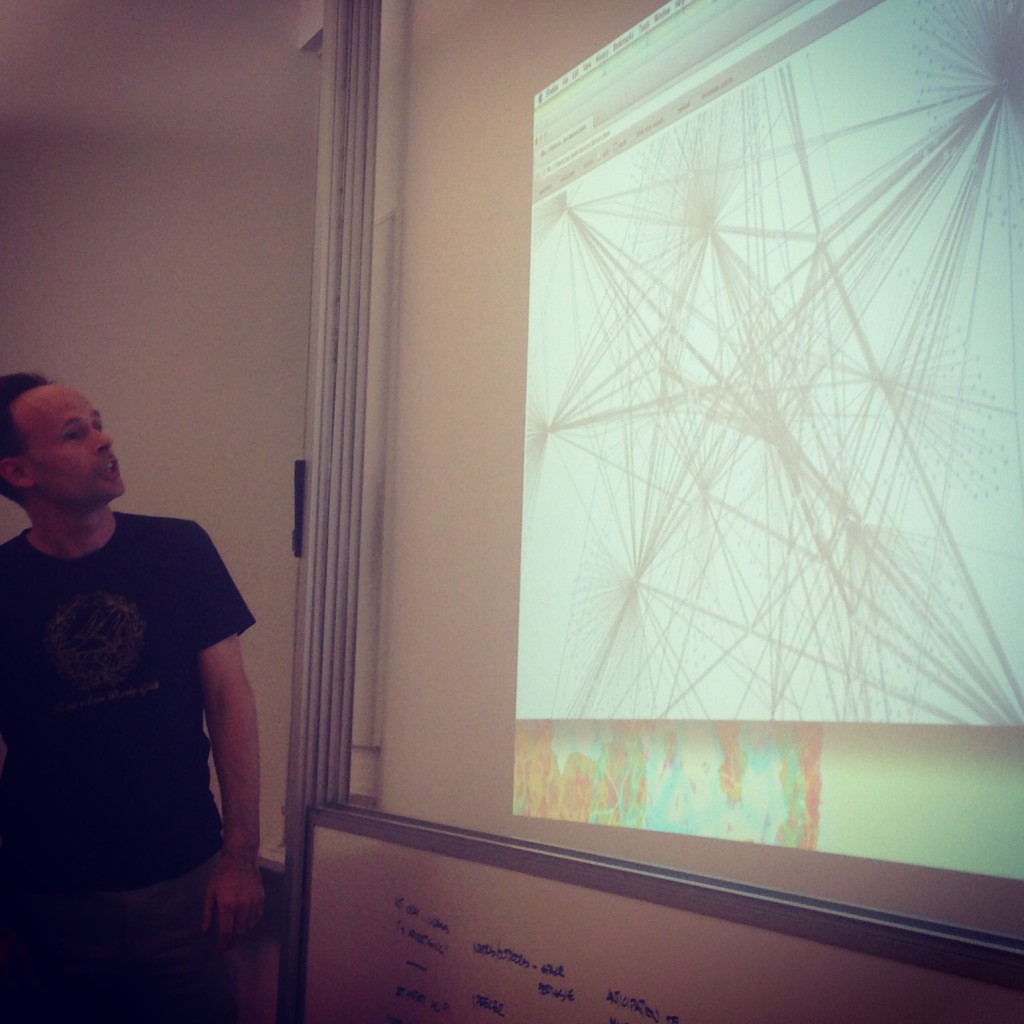

Aaron exposes the power structure that is the donor walls of New York City – Pratt Institute, 14th Street.

On Tuesday nights I’ve been accompanying Seb and Aaron to teach a graduate class at Pratt Institute called Museums and the Network (subtitle Caravvagio in the age of Dan Flavin lights). The syllabus states: “Museums have been deeply impacted by the changes in the digital landscape.

At the same time they are buffeted by the demographic transformations of their constituent communities and changes in education. The collapsing barriers to collection, publishing and distribution afforded by the internet have further eroded the museum’s role as cultural conduit.”

It’s a wonderful learning environment, full of serious play and playful seriousness; theoretical ideas and practical examples. Just like the real Cooper-Hewitt Labs.

The students’ ultimate project will be to create an exhibit – perhaps out of the collection of donor walls of New York’s museums – one of the class’ first assignments. Donor walls loom large and prominently in the cultural institutions here. So much of the work of the sector is funded through endowments and private donations.

Like the Cooper-Hewitt, the students have started by digitising the donor walls and turning all their data into a structured open form so that they (and others) can start to tell stories out of it and present it through a web interface. They are gradually building up to staging an exhibition, “that exists at the intersection of the physical and the internet, from concept through development”.

The readings from this class have become my Instapaper companions as I commute for 40 minutes up the island of Manhattan each morning, and home again. I’ve also started to imagine a museum exhibit of my time in New York. Or perhaps it’s a conceptual art piece or a marketing intervention.

Whatever it is, you enter a space that looks like a real installation install. It’s probably painted off-white. There are pieces of papers on the wall with numbers, plinths on which objects could stand, sheets of blank paper in cabinet drawers, empty glass cases and maybe even 3D replicas of framed paintings that are also off-white.

A docent (in New Zealand we call them visitor hosts) guides you to an “information desk” where you can collect a mobile guide or brochures in exchange for your own personal cell phone, which you must check in. You are told that you can read whatever you like on the guide, but you must not erase the content you find there or create new content.

You are told how to use the phone to interact with the numbers on the walls.

Exploring the various applications on the phone you begin to uncover the story of the visitor who came before you. You read their text messages, look at their Instagram feed, explore their Twitter profile and open their photographs (which show photographs of objects, followed by labels with prominent numbers matching the ones on the walls). Maybe there’s a projector installed.

As you stand next to your friend in front of the same object (perhaps it’s the 3D-printed white replica of a framed painting with no texture to indicate the pictorial content) you realize that you have different content on your phones. They are seeing a Van Gogh at #7, you a Rembrandt. You talk about what you (can’t) see. Perhaps there are also some color-less 3D printed replicas of sculptural pieces or other collection items you can hold.

Other audience members text #7 to the number they have been given, and are sent back a record for an object. This is a project that Micah has been playing with using the collections API, using Twilio.

As you hand back the device, you are given the address of a museum where you can see the collection and a URL for it online. Perhaps you exit through a gift shop where you can buy printed postcards of what you didn’t see.

Enough speculation. This is not the collaborative project I came here to consider. Nor am I entirely serious (well, maybe a little bit serious).

(Record of trip to New Museum)

*

There are many comments I could make about the differences and similarities between what I’ve experienced in my short time in New York City and what is familiar to me back home.

At the risk of generalizing, I could talk about the constraints that the grant-based funding model here seem to place on the ability to play a long game with digital infrastructure or to embed sustainable museological practice into the fabric of the institution.

I could talk about how the Cooper-Hewitt seems to run on a skeleton staff of just 73 people, which is small (even by New Zealand standards), for a national institution. How museums I have worked with in New Zealand use visitor and market research and audience segmentation as a foundation for decision-making about programming opportunities, which seems less evident here.

I could mention how far ahead collection documentation and interpretation strategies seem in museums with equivalent missions in New Zealand such as Te Papa – where relating exhibition label text, narratives, external collections and content assets such as videos around online collections is now everyday practice.

I could talk about how ‘coffee plunger’ is a dirty word for French press, how people walk on the wrong side of the sidewalk, and how the light switches go up not down to power on the light. But these are just surface differences for the same basic human motivations.

What I want to highlight, however, isn’t any of these things. Nor is it a comparison. It’s the willingness I’ve seen of staff at the Cooper-Hewitt to start working together across disciplinary boundaries and departments (education/curatorial/digital media) to continue Bill Moggridge’s vision for an ‘active visitor’ to the museum.

This kind of cultural change takes time. (And time already moves slower in museums than the real world). It’s messy and confusing and identity-challenging. It’s hard to achieve when short-term priorities and established modes of operating keep jostling for the attention of the same staff who need to be its agents.

Yet everyone I have met in my short time here has been so friendly and willing to share information with me. Echoing the sentiment of many that I have talked to at the Cooper-Hewitt, I am also hugely grateful to Seb for his encouraging mentorship and guidance, and Aaron for challenging me to think harder.

As Larry Wall puts it in ‘Perl, the first postmodern computer language’, “these are the people who inhabit the intersections of the Venn diagrams”. The accessibility to experience made possible by the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York City will be so much richer for their efforts.

I hope it continues to grow and flourish for many years to come.

Virginia – This is a wonderful blog,particularly for any one working in a museum undergoing a digital and physical transformation. I think that’s just about everybody. I knew I’d be hooked when I saw the reference to David Foster Wallace. My museum is paying me to do conservation, right now, so I had to glance at headings and content, but I’ll be back for a better read tomorrow night! Many thanks for this thought provoking visit post

This is an excellent post that provides fascinating insights into changes happening at CHNDM and, more broadly, into the possibilities digital approaches present for interpreting and sharing collections. Thank you!

Very rich observations. Enabling “I do and I understand” is a challenge for institutions that want you to watch/observe rather than interact. Looking forward to more “phygital” spaces where interaction is possible between the location/objects and the experiencer through digital and mobile devices. More engagement that enables contributions by those who without these tools are behind the glass wall of ‘look, don’t touch, don’t even come close!’.